Thursday, May 27, 2010

The lemon tree

Tolan, Sandy. (2006). The lemon tree: an Arab, a Jew, and the heart of the Middle East. New York: Bloomsbury Pub. : Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrinck Publishers.

A patron called for this book; it has also been made into a film.

Monday, May 24, 2010

5 moguls

T.J. Stiles says these mogul biographies offer rich rewards

1. Andrew Carnegie. Joseph Frazier Wall. Oxford, 1970

In the past few decades we have seen a sweeping reassessment of the so-called robber barons of the 19th and early 20th centuries. The trend began in 1970 with Joseph Frazier Wall's "Andrew Carnegie"—a groundbreaking work that remains a pleasure to read. By turns a thoughtful sifter of the evidence, a sharp and amusing portraitist, and a storyteller with real panache, Wall brings a gift for clarity to both historical context and the blow-by-blow of business battles. His tales of intrigue among Carnegie's partners are particularly vivid. Carnegie wore many guises—he got his start as an entrepreneur through sweetheart deals, proved a ruthlessly efficient steelmaker and aspired to influence world affairs—and this book artfully integrates them all.

2. The Life and Legend of Jay Gould. Maury Klein. Johns Hopkins, 1986

Jay Gould's "reputation for being cold and aloof," writes Maury Klein, "owed much to the fact that he was a shy, reserved man whose emotions registered on so small a scale, such as tearing bits of paper or tapping a pencil, that only initiates recognized them." Such insight and literary grace explain why Klein's "The Life and Legend of Jay Gould" remains the definitive work on this controversial tycoon. The author narrates with wry humor and verve such episodes as the corruption-riddled battle among financiers for control of the Erie Railroad in 1868 and Gould's attempt to corner the gold market in 1869. But Klein's greatest contribution may be in describing Gould's later years, when he proved a master corporate strategist, building an empire around the Missouri Pacific railroad.

3. Morgan Jean Strouse. Random House, 1999

As America's leading banker, J.P. Morgan played a role unlike any other business titan of his age, influencing one industry after another. He reorganized the chaotic railroads and forged U.S. Steel and General Electric—in other words, he was the father of the trusts that others set out to bust. "When the federal government ran out of gold in 1895, Morgan raised $65 million and made sure it stayed in the Treasury's coffers," writes Jean Strouse in this elegant biography. "When a panic started in New York in 1907, he led teams of bankers to stop it." Strouse is masterly, whether addressing finance, family, art or the human condition. Her portrait of Morgan's first rare-book librarian, Belle da Costa Greene—the daughter of Harvard's first black graduate, she passed as Portuguese—is but one example of Strouse's literary gifts and appreciation for the importance of secondary characters in a good biography.

4. Fallen Founder. Nancy Isenberg. Viking, 2007

It is not easy to get a fair hearing when you have killed the man on the $10 bill. But Aaron Burr is treated with scholarly care and writerly sympathy by Nancy Isenberg in "Fallen Founder." A hero in the American Revolution and the country's third vice president, Burr founded the forerunner of J.P. Morgan Chase: the Manhattan Co., a water company and bank. He pioneered modern political methods by systematically identifying and organizing voters, contributors and activists. Isenberg offers evidence that Burr was no villain in the 1804 duel that killed Alexander Hamilton. Three years later, Burr was arrested for what his enemies called a conspiracy to set up an independent state in the west; he was tried for treason and exonerated, then went on to become an influential New York lawyer. An astonishing life.

5. Pulitzer. James McGrath Morris. Harper, 2010

Today's reporters and media tycoons would do well to study James McGrath Morris's life of Joseph Pulitzer, the journalist, editor and entrepreneur. A proverbial penniless immigrant (a German-speaking Hungarian Jew), Pulitzer fought for the Union in the Civil War, then moved to St. Louis. There he learned English and the news business. His rapid rise in journalism was interwoven with politics, a natural twist, since newspapers were overtly partisan. He briefly held elected office but found greatness as a newspaper owner. Morris is fascinating on Pulitzer as a working (make that hard-working) reporter and editor who understood how to grab his readers—and saw where his industry was going (or could go).

—Mr. Stiles is the author of "The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt," winner of the 2009 National Book Award and the 2010 Pulitzer Prize, now available in paperback from Vintage.Printed in The Wall Street Journal, page W8

22 May 2010

1. Andrew Carnegie. Joseph Frazier Wall. Oxford, 1970

In the past few decades we have seen a sweeping reassessment of the so-called robber barons of the 19th and early 20th centuries. The trend began in 1970 with Joseph Frazier Wall's "Andrew Carnegie"—a groundbreaking work that remains a pleasure to read. By turns a thoughtful sifter of the evidence, a sharp and amusing portraitist, and a storyteller with real panache, Wall brings a gift for clarity to both historical context and the blow-by-blow of business battles. His tales of intrigue among Carnegie's partners are particularly vivid. Carnegie wore many guises—he got his start as an entrepreneur through sweetheart deals, proved a ruthlessly efficient steelmaker and aspired to influence world affairs—and this book artfully integrates them all.

2. The Life and Legend of Jay Gould. Maury Klein. Johns Hopkins, 1986

Jay Gould's "reputation for being cold and aloof," writes Maury Klein, "owed much to the fact that he was a shy, reserved man whose emotions registered on so small a scale, such as tearing bits of paper or tapping a pencil, that only initiates recognized them." Such insight and literary grace explain why Klein's "The Life and Legend of Jay Gould" remains the definitive work on this controversial tycoon. The author narrates with wry humor and verve such episodes as the corruption-riddled battle among financiers for control of the Erie Railroad in 1868 and Gould's attempt to corner the gold market in 1869. But Klein's greatest contribution may be in describing Gould's later years, when he proved a master corporate strategist, building an empire around the Missouri Pacific railroad.

3. Morgan Jean Strouse. Random House, 1999

As America's leading banker, J.P. Morgan played a role unlike any other business titan of his age, influencing one industry after another. He reorganized the chaotic railroads and forged U.S. Steel and General Electric—in other words, he was the father of the trusts that others set out to bust. "When the federal government ran out of gold in 1895, Morgan raised $65 million and made sure it stayed in the Treasury's coffers," writes Jean Strouse in this elegant biography. "When a panic started in New York in 1907, he led teams of bankers to stop it." Strouse is masterly, whether addressing finance, family, art or the human condition. Her portrait of Morgan's first rare-book librarian, Belle da Costa Greene—the daughter of Harvard's first black graduate, she passed as Portuguese—is but one example of Strouse's literary gifts and appreciation for the importance of secondary characters in a good biography.

4. Fallen Founder. Nancy Isenberg. Viking, 2007

It is not easy to get a fair hearing when you have killed the man on the $10 bill. But Aaron Burr is treated with scholarly care and writerly sympathy by Nancy Isenberg in "Fallen Founder." A hero in the American Revolution and the country's third vice president, Burr founded the forerunner of J.P. Morgan Chase: the Manhattan Co., a water company and bank. He pioneered modern political methods by systematically identifying and organizing voters, contributors and activists. Isenberg offers evidence that Burr was no villain in the 1804 duel that killed Alexander Hamilton. Three years later, Burr was arrested for what his enemies called a conspiracy to set up an independent state in the west; he was tried for treason and exonerated, then went on to become an influential New York lawyer. An astonishing life.

5. Pulitzer. James McGrath Morris. Harper, 2010

Today's reporters and media tycoons would do well to study James McGrath Morris's life of Joseph Pulitzer, the journalist, editor and entrepreneur. A proverbial penniless immigrant (a German-speaking Hungarian Jew), Pulitzer fought for the Union in the Civil War, then moved to St. Louis. There he learned English and the news business. His rapid rise in journalism was interwoven with politics, a natural twist, since newspapers were overtly partisan. He briefly held elected office but found greatness as a newspaper owner. Morris is fascinating on Pulitzer as a working (make that hard-working) reporter and editor who understood how to grab his readers—and saw where his industry was going (or could go).

—Mr. Stiles is the author of "The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt," winner of the 2009 National Book Award and the 2010 Pulitzer Prize, now available in paperback from Vintage.Printed in The Wall Street Journal, page W8

22 May 2010

Labels:

Finance,

Media,

News,

Politics,

US History

How the West won

O, that life were quite this simple.

The Granger Collection - A cartoon from 1949, soon after formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization as a counter to the Soviet Union.

There is no denying the corruption of the Soviet system, and its internal rot, but that does not license such ridiculous comments as this passage:

"The West, in the summer of 1979, was in poor condition, and Europe was not producing the answers. Creativity would have to come from the Atlantic again, and it did. Margaret Thatcher emerged in May, and Ronald Reagan was elected President in 1980."

Mrs. Thatcher, the author writes, "knew when to be Circe and when to be the nanny from hell." As for President Reagan, Mr. Stone wisely quotes the man himself. "If it moves, tax it," Reagan said, summing up the liberal outlook to which he was adamantly opposed; "if it keeps moving, regulate it. And if it stops moving, subsidize it." The story of the 1980s, in Mr. Stone's bracing account, is one of the West finding its true self after years of wandering in the wilderness, while the Soviet experiment at long last revealed itself to be the sham it had been from the beginning.

Yes, Thatcher got the UK moving, in large part, or at least in good part, by standing up to the miners and asserting her leadership. But Reagan's role is over-simplified.

If there is a law Congress passes that you don't like, break it surreptitiously; if your economic theories don't work, and in fact make matters worse, engage in Keynisian deficit spending and keep telling the same lies over and over. Say one thing, do another.

The Granger Collection - A cartoon from 1949, soon after formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization as a counter to the Soviet Union.

There is no denying the corruption of the Soviet system, and its internal rot, but that does not license such ridiculous comments as this passage:

"The West, in the summer of 1979, was in poor condition, and Europe was not producing the answers. Creativity would have to come from the Atlantic again, and it did. Margaret Thatcher emerged in May, and Ronald Reagan was elected President in 1980."

Mrs. Thatcher, the author writes, "knew when to be Circe and when to be the nanny from hell." As for President Reagan, Mr. Stone wisely quotes the man himself. "If it moves, tax it," Reagan said, summing up the liberal outlook to which he was adamantly opposed; "if it keeps moving, regulate it. And if it stops moving, subsidize it." The story of the 1980s, in Mr. Stone's bracing account, is one of the West finding its true self after years of wandering in the wilderness, while the Soviet experiment at long last revealed itself to be the sham it had been from the beginning.

Yes, Thatcher got the UK moving, in large part, or at least in good part, by standing up to the miners and asserting her leadership. But Reagan's role is over-simplified.

If there is a law Congress passes that you don't like, break it surreptitiously; if your economic theories don't work, and in fact make matters worse, engage in Keynisian deficit spending and keep telling the same lies over and over. Say one thing, do another.

Saturday, May 22, 2010

Thursday, May 20, 2010

A man of protean passions

Jack London is known as the writer of what are now children's books, about animals, mainly. Yet, as is usual, there is more to him than the simple image. This review is fascinating: Theroux chastices Haley for obsessing over London's possible homosexuality, yet calls it still a valuable London biography.

Back From the Beyond

The author known for 'The Call of the Wild' was a man of protean passions

By Alexander Theroux

Jack London, born John Griffith Chaney in 1876, grew up a working-class, fatherless boy in Oakland, Calif., and spent his teen years riding the rails, thieving oysters, sailing on a seal-hunting schooner and toiling as what he would later call a "work beast," shoveling coal, working in a cannery, loading bobbins in a jute mill, ironing shirts in a steam laundry. Somehow he also found time to spend in libraries and became an enthusiastic reader of novels and travel books at an early age.

Jack London at his desk in 1916, the year he died at age 40.

On the sealing schooner in 1873 he had survived a harrowing run-in with a typhoon. The stories he told about the storm after his return home prompted his mother, when she saw the announcement of a writing contest in the San Francisco Morning Call asking for descriptive articles by local writers 22 years old or younger, to urge her son to write up his typhoon experience for the contest. The 17-year-old London won the $25 first prize, "beating out students from Stanford and Berkeley with his eighth-grade education," writes biographer James L. Haley in "Wolf: The Lives of Jack London." The prize money, Mr. Haley notes, was the equivalent of a month's wages in the London household. "Jack London, author, was born."

The young man plunged into writing short stories—but found that he couldn't sell them. He made a trip to the East Coast in 1874 (spending a month unjustly jailed as a vagrant in Buffalo), returned to Oakland and enrolled at the University of California at Berkeley, only to withdraw after a semester. Hearing news of a gold strike in the Canadian Yukon Territory, he was hit by a case of "Klondicitis" and headed north. He came back flat broke at 22, more determined than ever to make a living as a writer. London's first-hand experience of life in America's penniless subculture turned him into a committed socialist for the rest of his life—which was not all that long. He died at age 40; during the intervening two decades he would become the highest-paid writer in the country.

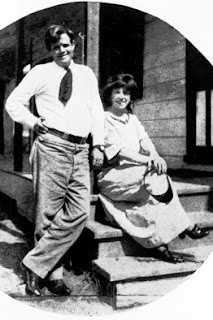

Mr. London with his wife, Charmian, in an undated photograph.

The book that made him a national celebrity, at age 27, was "The Call of the Wild," a novel about a domesticated dog that eventually finds its true self in the raw life of a sled dog in the Yukon. Suddenly it seemed that London knew everybody in the writing world. Sinclair Lewis, Ambrose Bierce, Emma Goldman, Upton Sinclair, Lincoln Steffens, Ida Tarbell and many others counted the young, red-blooded author as their friend.

Mr. Haley says that he does not intend, with "Wolf," to recapitulate what has already been written about London, whether in adulatory biographies or lit-crit monographs. The author wants to explore the forgotten, the "real" Jack London, concluding that "what London needs is a biographer's eye—not the eye of a vestal flametender, nor an acolyte, nor a revisionist, but a biographer's eye, from totally outside the existing circle." Thus we are treated to portraits of London's father, William Chaney, an itinerant evangelizing astrologer; of his shrewish mother, Flora Wellman, a woman who was born into wealth in Ohio and fled both; and of John London, a Civil War veteran from Pennsylvania who married Flora when London was eight months old, giving her a "chance at respectability."

We also meet London's demanding, unforgiving first wife, Bessie, and their two daughters; his African- American wet nurse, a splendid force in his life, named Virginia Prentiss; and, notably, the lusty and lovely but often traduced Charmian Kittredge, the offspring of parents who had dabbled in free love, whom London married on a lecture tour in Chicago in 1906.

Prolific, irrepressible, madly energetic, London wrote a thousand words a day without fail, compulsively, whether or not he was inspired. At his peak he often wrote as many as two books a year. In 1913 alone he published the story collection "The Night Born," two novels ("The Abysmal Brute" and "The Valley of the Moon"), along with his famous "alcoholic memoir" "John Barleycorn," in which he confessed to a lifelong struggle with booze. Temperance advocates used "John Barleycorn" in their push for prohibition; liquor companies denounced it; a popular movie was made of it; ministers cited it in sermons.

London lived hard and intensely, and the plural "lives" to which Mr. Haley refers in the book's subtitle sound plausible. London was a reporter as well as a novelist—Hearst paid him to cover the Russo-Japanese War in 1904—and traveled to the far ends of the planet. He was an omnivorous reader. On cross-country jaunts he lectured about the evils of capitalism. He ate indiscriminately (raw pressed duck was a favorite) and smoked cigarettes until the end of his life. A free spirit, he loved bicycling, flying kites and listening to music—Charmian was a virtuoso pianist. Having traveled to Hawaii and surfed "until the tropical sun almost killed him," London "introduced the sport to the world" in 1911 with "The Cruise of the Snark," an account of a Pacific sailing expedition.

Although London was famous for depicting the brutality of nature in his work, he also celebrated animals in novels such as "The Sea-Wolf" and "White Fang" and was tender-hearted toward them in life. London owned a California ranch, where he kept horses, dogs and pigs. Upon seeing a bullfight in Quito, Ecuador, in 1909, he found it so revolting that he excoriated the sport in his story "The Madness of John Harned." London wept at the deaths of his pets.

The common picture of London presents a robustly physical man with, sadly for Charmian, an almost athletic enthusiasm for philandering. But Mr. Haley wants to give us the "real" Jack London, and so—perhaps inevitably, given the times we live in and the nature of contemporary literary biography—we are treated to endless speculation about London's possible homosexuality. In a July 1903 letter to Charmian, written on the cusp of their marriage and obviously seeking her sympathy, London laments that he has "never had a comrade" and yearns for a "great Man-Comrade" who should be "so much one with me that we could never misunderstand," adding: "He should love the flesh, as he should the spirit."

[BK_Cover2]

Wolf: The Lives of Jack London

By James L. Haley

Basic Books, 364 pages, $29.95

* Read an excerpt

Mr. Haley makes much of this. He also focuses attention on London's friendship with the poet George Sterling. London called him the "Greek" on account of his classical good looks; Sterling called him Wolf. The two were indeed close. Sterling's editorial gifts influenced "The Call of the Wild," and Charmian, before the marriage, fretted about how much time London spent with his friend.

It wouldn't have been the first time that a fiancée resented her intended's pals, but Mr. Haley sees something more. "Sterling alone held the potential to embrace a soul as vast and complex as his own," he writes. "London was never bashful about recommending the therapeutic value of recreational sex, and Sterling was equally forthright in his contention that orgasms liberated creativity. Although the most noted affairs of both men were certainly with women, it seems not improbable that Wolf and the Greek found time and circumstance for one another, but neither man ever committed to paper how deep their relationship extended." Readers can be pardoned for thinking it seems not improbable that London, given the chance, would punch Mr. Haley in the nose.

Mr. Haley is almost prurient with his gaydar. He speculates on the nature of male comradeship during the 17-year-old London's sealing trip to Japan. The author finds homosexual undertones in the brutal naturalism of "The Sea-Wolf." In London's boxing novel, "The Game," Mr. Haley finds "surprisingly" lyrical descriptions of male beauty, stripped and muscular, and he raises an eyebrow over photographs of London "minimally-clad" in "he-man poses." London "was proud of his blond-beastly body," we're told, "and was not shy about showing it off. Unpublished nudes of him also exist."

Mr. Haley concedes—it feels grudging—that he has no solid evidence for London's homosexuality, yet he insists on keeping the theme alive throughout the book. That misguided decision mars "Wolf" (as does, in a minor way, the author's maddening misuse of the word "disinterest"). But this is still a valuable London biography. It surpasses Irving Stone's 1938 "Sailor on Horseback," giving us a well-delineated picture of a singular, complicated figure, a socialist who signed his letters "Yours for the revolution, Jack London" but who traveled for decades—often first-class—with an Asian servant who was required to call him "Master." London was an anti-capitalist who wildly speculated in schemes like importing and selling Australian eucalyptus trees in hopes that he would make a killing as they replaced Eastern hardwoods—in one season he planted 16,000 of them. He was a polemicist who pleaded for the waifs in London but built a four-story castle on the extravagant 1,000-acre Beauty Ranch near Glen Ellen, Calif. "His socialism was not about banning wealth," Mr. Haley notes. "It was about banning wealth accrued by exploiting others."

These days we have little sense of the literary glory that Jack London. When he is read at all, it is predominantly as a writer of boy's books. The daring novel he wrote in 1907, "Before Adam," is a fiercely imaginative, Darwinian tale about a caged lion in a circus, and it is fascinating in its exploration of atavistic memory. The book sold 65,000 copies a century ago but is virtually unknown today. Thanks to James Haley's zeal, the author of that novel, not just the man of "The Call of the Wild" fame, is before us again.

—Mr. Theroux's latest novel is "Laura Warholic: Or, The Sexual Intellectual" (Fantagraphics).

Back From the Beyond

The author known for 'The Call of the Wild' was a man of protean passions

By Alexander Theroux

Jack London, born John Griffith Chaney in 1876, grew up a working-class, fatherless boy in Oakland, Calif., and spent his teen years riding the rails, thieving oysters, sailing on a seal-hunting schooner and toiling as what he would later call a "work beast," shoveling coal, working in a cannery, loading bobbins in a jute mill, ironing shirts in a steam laundry. Somehow he also found time to spend in libraries and became an enthusiastic reader of novels and travel books at an early age.

Jack London at his desk in 1916, the year he died at age 40.

On the sealing schooner in 1873 he had survived a harrowing run-in with a typhoon. The stories he told about the storm after his return home prompted his mother, when she saw the announcement of a writing contest in the San Francisco Morning Call asking for descriptive articles by local writers 22 years old or younger, to urge her son to write up his typhoon experience for the contest. The 17-year-old London won the $25 first prize, "beating out students from Stanford and Berkeley with his eighth-grade education," writes biographer James L. Haley in "Wolf: The Lives of Jack London." The prize money, Mr. Haley notes, was the equivalent of a month's wages in the London household. "Jack London, author, was born."

The young man plunged into writing short stories—but found that he couldn't sell them. He made a trip to the East Coast in 1874 (spending a month unjustly jailed as a vagrant in Buffalo), returned to Oakland and enrolled at the University of California at Berkeley, only to withdraw after a semester. Hearing news of a gold strike in the Canadian Yukon Territory, he was hit by a case of "Klondicitis" and headed north. He came back flat broke at 22, more determined than ever to make a living as a writer. London's first-hand experience of life in America's penniless subculture turned him into a committed socialist for the rest of his life—which was not all that long. He died at age 40; during the intervening two decades he would become the highest-paid writer in the country.

Mr. London with his wife, Charmian, in an undated photograph.

The book that made him a national celebrity, at age 27, was "The Call of the Wild," a novel about a domesticated dog that eventually finds its true self in the raw life of a sled dog in the Yukon. Suddenly it seemed that London knew everybody in the writing world. Sinclair Lewis, Ambrose Bierce, Emma Goldman, Upton Sinclair, Lincoln Steffens, Ida Tarbell and many others counted the young, red-blooded author as their friend.

Mr. Haley says that he does not intend, with "Wolf," to recapitulate what has already been written about London, whether in adulatory biographies or lit-crit monographs. The author wants to explore the forgotten, the "real" Jack London, concluding that "what London needs is a biographer's eye—not the eye of a vestal flametender, nor an acolyte, nor a revisionist, but a biographer's eye, from totally outside the existing circle." Thus we are treated to portraits of London's father, William Chaney, an itinerant evangelizing astrologer; of his shrewish mother, Flora Wellman, a woman who was born into wealth in Ohio and fled both; and of John London, a Civil War veteran from Pennsylvania who married Flora when London was eight months old, giving her a "chance at respectability."

We also meet London's demanding, unforgiving first wife, Bessie, and their two daughters; his African- American wet nurse, a splendid force in his life, named Virginia Prentiss; and, notably, the lusty and lovely but often traduced Charmian Kittredge, the offspring of parents who had dabbled in free love, whom London married on a lecture tour in Chicago in 1906.

Prolific, irrepressible, madly energetic, London wrote a thousand words a day without fail, compulsively, whether or not he was inspired. At his peak he often wrote as many as two books a year. In 1913 alone he published the story collection "The Night Born," two novels ("The Abysmal Brute" and "The Valley of the Moon"), along with his famous "alcoholic memoir" "John Barleycorn," in which he confessed to a lifelong struggle with booze. Temperance advocates used "John Barleycorn" in their push for prohibition; liquor companies denounced it; a popular movie was made of it; ministers cited it in sermons.

London lived hard and intensely, and the plural "lives" to which Mr. Haley refers in the book's subtitle sound plausible. London was a reporter as well as a novelist—Hearst paid him to cover the Russo-Japanese War in 1904—and traveled to the far ends of the planet. He was an omnivorous reader. On cross-country jaunts he lectured about the evils of capitalism. He ate indiscriminately (raw pressed duck was a favorite) and smoked cigarettes until the end of his life. A free spirit, he loved bicycling, flying kites and listening to music—Charmian was a virtuoso pianist. Having traveled to Hawaii and surfed "until the tropical sun almost killed him," London "introduced the sport to the world" in 1911 with "The Cruise of the Snark," an account of a Pacific sailing expedition.

Although London was famous for depicting the brutality of nature in his work, he also celebrated animals in novels such as "The Sea-Wolf" and "White Fang" and was tender-hearted toward them in life. London owned a California ranch, where he kept horses, dogs and pigs. Upon seeing a bullfight in Quito, Ecuador, in 1909, he found it so revolting that he excoriated the sport in his story "The Madness of John Harned." London wept at the deaths of his pets.

The common picture of London presents a robustly physical man with, sadly for Charmian, an almost athletic enthusiasm for philandering. But Mr. Haley wants to give us the "real" Jack London, and so—perhaps inevitably, given the times we live in and the nature of contemporary literary biography—we are treated to endless speculation about London's possible homosexuality. In a July 1903 letter to Charmian, written on the cusp of their marriage and obviously seeking her sympathy, London laments that he has "never had a comrade" and yearns for a "great Man-Comrade" who should be "so much one with me that we could never misunderstand," adding: "He should love the flesh, as he should the spirit."

[BK_Cover2]

Wolf: The Lives of Jack London

By James L. Haley

Basic Books, 364 pages, $29.95

* Read an excerpt

Mr. Haley makes much of this. He also focuses attention on London's friendship with the poet George Sterling. London called him the "Greek" on account of his classical good looks; Sterling called him Wolf. The two were indeed close. Sterling's editorial gifts influenced "The Call of the Wild," and Charmian, before the marriage, fretted about how much time London spent with his friend.

It wouldn't have been the first time that a fiancée resented her intended's pals, but Mr. Haley sees something more. "Sterling alone held the potential to embrace a soul as vast and complex as his own," he writes. "London was never bashful about recommending the therapeutic value of recreational sex, and Sterling was equally forthright in his contention that orgasms liberated creativity. Although the most noted affairs of both men were certainly with women, it seems not improbable that Wolf and the Greek found time and circumstance for one another, but neither man ever committed to paper how deep their relationship extended." Readers can be pardoned for thinking it seems not improbable that London, given the chance, would punch Mr. Haley in the nose.

Mr. Haley is almost prurient with his gaydar. He speculates on the nature of male comradeship during the 17-year-old London's sealing trip to Japan. The author finds homosexual undertones in the brutal naturalism of "The Sea-Wolf." In London's boxing novel, "The Game," Mr. Haley finds "surprisingly" lyrical descriptions of male beauty, stripped and muscular, and he raises an eyebrow over photographs of London "minimally-clad" in "he-man poses." London "was proud of his blond-beastly body," we're told, "and was not shy about showing it off. Unpublished nudes of him also exist."

Mr. Haley concedes—it feels grudging—that he has no solid evidence for London's homosexuality, yet he insists on keeping the theme alive throughout the book. That misguided decision mars "Wolf" (as does, in a minor way, the author's maddening misuse of the word "disinterest"). But this is still a valuable London biography. It surpasses Irving Stone's 1938 "Sailor on Horseback," giving us a well-delineated picture of a singular, complicated figure, a socialist who signed his letters "Yours for the revolution, Jack London" but who traveled for decades—often first-class—with an Asian servant who was required to call him "Master." London was an anti-capitalist who wildly speculated in schemes like importing and selling Australian eucalyptus trees in hopes that he would make a killing as they replaced Eastern hardwoods—in one season he planted 16,000 of them. He was a polemicist who pleaded for the waifs in London but built a four-story castle on the extravagant 1,000-acre Beauty Ranch near Glen Ellen, Calif. "His socialism was not about banning wealth," Mr. Haley notes. "It was about banning wealth accrued by exploiting others."

These days we have little sense of the literary glory that Jack London. When he is read at all, it is predominantly as a writer of boy's books. The daring novel he wrote in 1907, "Before Adam," is a fiercely imaginative, Darwinian tale about a caged lion in a circus, and it is fascinating in its exploration of atavistic memory. The book sold 65,000 copies a century ago but is virtually unknown today. Thanks to James Haley's zeal, the author of that novel, not just the man of "The Call of the Wild" fame, is before us again.

—Mr. Theroux's latest novel is "Laura Warholic: Or, The Sexual Intellectual" (Fantagraphics).

Saturday, May 15, 2010

Books on Statesmen

Evan Thomas chooses distinguished books on statesmen

1. Present at the Creation. Dean Acheson. Norton, 1969. [327.73 A (International Relations) and 973.918 A (North American history)]

Most people, when they are in the midst of history being made, are too caught up in the moment to see its larger meaning. Not the great American statesman Dean Acheson: His aptly named autobiography captures the precise date, on Feb. 27, 1947, when the duties of Pax Britannica passed to Pax Americana. Britain on that day told the U.S. that the British were no longer able to help protect Turkey and Greece from Soviet expansion; America was on its own. "We drank a martini or two to the confusion of our enemies," recorded Acheson, who would go on to become secretary of state (1949-53). Written with grandeur, verve and a certain puckish delight, "Present at the Creation" is the frankest and most gripping work by a statesman since Ulysses S. Grant's 1885 autobiography.

Grant's work is magnificent.

2. Passionate Sage . Joseph Ellis. Norton, 1993. 973.4409 E

Over the past decade or so, the best-seller lists have included some big and wonderfully readable biographies of the Founders, but the best portrait of a Revolutionary-era statesman is this slim, dense and relatively little known volume about John Adams. Written by Joseph Ellis before his own blockbuster biographies of Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, "Passionate Sage" is structured thematically. It demands a reader's close attention, but the reward is great. Ellis shows that Adams was able to use his shrewd understanding of human vanity, especially his own, to shape a government system of checks and balances. Ellis has fun with the irrepressible Adams, who like his old friend and rival Jefferson was obsessed with his place in history. "I thought my Books, as well as myself, were forgotten," Adams joked to Jefferson in 1813. "But behold! I am to become a great Man in my expiring moments."

3. Master of the Senate. Robert A. Caro. Knopf, 2002. B Johnson C

The United States Senate is, generally speaking, a boring place. On most days the chamber is empty, or a single senator drones on as others wander in and out. Yet Robert Caro—researching "Master of the Senate," the third volume in his magisterial series "The Years of Lyndon Johnson"—sat day after day high in the public galleries, conjuring the drama of an earlier time when giants, or one particular giant, strode the Senate floor. Caro's LBJ cajoles, whines, blusters, deceives, intimidates—and gets the Senate, still dominated in the 1950s by Southern Democrats, to pass the first-ever civil-rights bill. Johnson is crude, to put it mildly—Caro describes him on a "monument of a toilet," browbeating secretaries, assistants and other lawmakers. But if only we had someone like LBJ in Congress today.

4. The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt. Edmund Morris. Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, 1979. B Roosevelt M

Edmund Morris virtually inhabits his subject in "The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt" (the first book in a three-volume series that will conclude later this year). His feel for Roosevelt—a bragging, bullying, bellowing, yet somehow tender and always steadfast young man—is so tactile that it verges on the sensuous. "He was dubbed 'The Chief of the Dudes,' and satirized as a tight-trousered snob given to sucking the knob of his ivory cane," Morris writes. This volume, about the pre-presidential Roosevelt, is more engaging than the one that followed. Presidential biographies are almost inherently heavy going because presidents must always be doing too many things at once. But Morris, like TR, is never dull.

5. The Proud Tower. Barbara Tuchman. Macmillan, 1962. 901.941 T (also 909.82, and 940.28, and 940.311)

The turn of the 20th century was a great age of statesmen, or so it seemed. Dressed handsomely in frock coats, cutaways and top hats, they gravely, pompously, naïvely held international conferences that vowed to put an end to war, forever. Reading Barbara Tuchman's collection of elegant, elegiac essays about this period, you can almost hear the ice cracking beneath their feet. (The title comes from an Edgar Allan Poe poem, "While from a proud tower in the town / Death looks gigantically down.") One portrait is particularly captivating: the tragedy of Thomas Brackett Reed, the House speaker who tried to stop America from lunging into the race for empire in the last years of the 19th century. Reed was brilliant and indomitable, but he was unable to stand in the way of the lust for conquest and dominion that seized America and much of the civilized world on the eve of World War I.

—Mr. Thomas is the author of The war lovers : Roosevelt, Lodge, Hearst, and the rush to empire, 1898. 973.891 T

Printed in The Wall Street Journal, page W8

1. Present at the Creation. Dean Acheson. Norton, 1969. [327.73 A (International Relations) and 973.918 A (North American history)]

Most people, when they are in the midst of history being made, are too caught up in the moment to see its larger meaning. Not the great American statesman Dean Acheson: His aptly named autobiography captures the precise date, on Feb. 27, 1947, when the duties of Pax Britannica passed to Pax Americana. Britain on that day told the U.S. that the British were no longer able to help protect Turkey and Greece from Soviet expansion; America was on its own. "We drank a martini or two to the confusion of our enemies," recorded Acheson, who would go on to become secretary of state (1949-53). Written with grandeur, verve and a certain puckish delight, "Present at the Creation" is the frankest and most gripping work by a statesman since Ulysses S. Grant's 1885 autobiography.

Grant's work is magnificent.

2. Passionate Sage . Joseph Ellis. Norton, 1993. 973.4409 E

Over the past decade or so, the best-seller lists have included some big and wonderfully readable biographies of the Founders, but the best portrait of a Revolutionary-era statesman is this slim, dense and relatively little known volume about John Adams. Written by Joseph Ellis before his own blockbuster biographies of Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, "Passionate Sage" is structured thematically. It demands a reader's close attention, but the reward is great. Ellis shows that Adams was able to use his shrewd understanding of human vanity, especially his own, to shape a government system of checks and balances. Ellis has fun with the irrepressible Adams, who like his old friend and rival Jefferson was obsessed with his place in history. "I thought my Books, as well as myself, were forgotten," Adams joked to Jefferson in 1813. "But behold! I am to become a great Man in my expiring moments."

3. Master of the Senate. Robert A. Caro. Knopf, 2002. B Johnson C

The United States Senate is, generally speaking, a boring place. On most days the chamber is empty, or a single senator drones on as others wander in and out. Yet Robert Caro—researching "Master of the Senate," the third volume in his magisterial series "The Years of Lyndon Johnson"—sat day after day high in the public galleries, conjuring the drama of an earlier time when giants, or one particular giant, strode the Senate floor. Caro's LBJ cajoles, whines, blusters, deceives, intimidates—and gets the Senate, still dominated in the 1950s by Southern Democrats, to pass the first-ever civil-rights bill. Johnson is crude, to put it mildly—Caro describes him on a "monument of a toilet," browbeating secretaries, assistants and other lawmakers. But if only we had someone like LBJ in Congress today.

4. The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt. Edmund Morris. Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, 1979. B Roosevelt M

Edmund Morris virtually inhabits his subject in "The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt" (the first book in a three-volume series that will conclude later this year). His feel for Roosevelt—a bragging, bullying, bellowing, yet somehow tender and always steadfast young man—is so tactile that it verges on the sensuous. "He was dubbed 'The Chief of the Dudes,' and satirized as a tight-trousered snob given to sucking the knob of his ivory cane," Morris writes. This volume, about the pre-presidential Roosevelt, is more engaging than the one that followed. Presidential biographies are almost inherently heavy going because presidents must always be doing too many things at once. But Morris, like TR, is never dull.

5. The Proud Tower. Barbara Tuchman. Macmillan, 1962. 901.941 T (also 909.82, and 940.28, and 940.311)

The turn of the 20th century was a great age of statesmen, or so it seemed. Dressed handsomely in frock coats, cutaways and top hats, they gravely, pompously, naïvely held international conferences that vowed to put an end to war, forever. Reading Barbara Tuchman's collection of elegant, elegiac essays about this period, you can almost hear the ice cracking beneath their feet. (The title comes from an Edgar Allan Poe poem, "While from a proud tower in the town / Death looks gigantically down.") One portrait is particularly captivating: the tragedy of Thomas Brackett Reed, the House speaker who tried to stop America from lunging into the race for empire in the last years of the 19th century. Reed was brilliant and indomitable, but he was unable to stand in the way of the lust for conquest and dominion that seized America and much of the civilized world on the eve of World War I.

—Mr. Thomas is the author of The war lovers : Roosevelt, Lodge, Hearst, and the rush to empire, 1898. 973.891 T

Printed in The Wall Street Journal, page W8

Labels:

American history,

US,

War,

WW1,

WW2

Thursday, May 13, 2010

The Red Book Of C.G. Jung

Modern men in the throes of a midlife crisis have been known to overhaul their careers, their relationships—even their bodies. Few, though, intentionally induce hallucinations in order to commune with demons and deities and end up creating a text transforming—at least indirectly—the entire field of psychology.

The Red Book Of C.G. Jung - owned by 3 libraries in Nassau, plus Great Neck

The Hammer Museum - at UCLA

Philemon Foundation - is preparing for publication the Complete Works of C. G. Jung.

Carl Gustav Jung was 37 when by most accounts he lost his soul. As psychological historian Sonu Shamdasani explained, "Jung had reached a point in 1912 when he'd achieved all of his youthful ambitions but felt that he'd lost meaning in his life, an existential crisis in which he simply neglected the areas of ultimate spiritual concern that were his main motivations in his youth."

In fact, the dilemma was so profound it eventually caused the father of analytical psychology to undergo a series of waking fantasies. Traveling from Zurich to Schaffhausen, Switzerland, in October 1913, Jung was roused by a troubling vision of "European-wide destruction." In place of the normally serene fields and trees, one of the era's pre-eminent thinkers saw the landscape submerged by a river of blood carrying forth not only detritus but also dead bodies. When that vision resurfaced a few weeks later—on the same journey—added to the mix was a voice telling him to "look clearly; all this would become real." World War I broke out the following summer.

These experiences prompted Jung to question his own sanity. But they also motivated him to embark on what turned out to be a 16-year self-seeking journey documented in a red leather journal titled "Liber Novus" (Latin for "New Book"). It features ethereal, often unsavory passages and shocking yet vibrant images expressing what Jung himself termed a "confrontation with the unconscious."

As Jung explained on the final page: "to the superficial observer, it will appear like madness." Yet Mr. Shamdasani says Jung was engaged in a clearly controlled experiment. "There wasn't anything like a psychosis," he insists. In fact, what emerged during what many describe as a crippling depression were Jung's groundbreaking theories on archetypes, the collective unconscious, and the process of individuation—the interior work one must engage in to become a person or individual.

The Red Book Of C.G. Jung - owned by 3 libraries in Nassau, plus Great Neck

The Hammer Museum - at UCLA

Philemon Foundation - is preparing for publication the Complete Works of C. G. Jung.

Carl Gustav Jung was 37 when by most accounts he lost his soul. As psychological historian Sonu Shamdasani explained, "Jung had reached a point in 1912 when he'd achieved all of his youthful ambitions but felt that he'd lost meaning in his life, an existential crisis in which he simply neglected the areas of ultimate spiritual concern that were his main motivations in his youth."

In fact, the dilemma was so profound it eventually caused the father of analytical psychology to undergo a series of waking fantasies. Traveling from Zurich to Schaffhausen, Switzerland, in October 1913, Jung was roused by a troubling vision of "European-wide destruction." In place of the normally serene fields and trees, one of the era's pre-eminent thinkers saw the landscape submerged by a river of blood carrying forth not only detritus but also dead bodies. When that vision resurfaced a few weeks later—on the same journey—added to the mix was a voice telling him to "look clearly; all this would become real." World War I broke out the following summer.

These experiences prompted Jung to question his own sanity. But they also motivated him to embark on what turned out to be a 16-year self-seeking journey documented in a red leather journal titled "Liber Novus" (Latin for "New Book"). It features ethereal, often unsavory passages and shocking yet vibrant images expressing what Jung himself termed a "confrontation with the unconscious."

As Jung explained on the final page: "to the superficial observer, it will appear like madness." Yet Mr. Shamdasani says Jung was engaged in a clearly controlled experiment. "There wasn't anything like a psychosis," he insists. In fact, what emerged during what many describe as a crippling depression were Jung's groundbreaking theories on archetypes, the collective unconscious, and the process of individuation—the interior work one must engage in to become a person or individual.

Labels:

Dreams,

Europe,

Psychology,

Switzerland

Wednesday, May 12, 2010

Blame it on the rain

Blame it on the rain : how the weather has shaped history and changed culture / Laura Lee.

Seemed a good idea, and was, but got repetitive.

Seemed a good idea, and was, but got repetitive.

The truth about dogs

The truth about dogs : an inquiry into the ancestry, social conventions, mental habits, and moral fiber of Canis familiaris. Stephen Budiansky.

Read bout it in Schlepping through the Alps. Started out well, got tedious, maybe another time.

Read bout it in Schlepping through the Alps. Started out well, got tedious, maybe another time.

Operation Mincemeat

Courtesy of Jeremy Montagu/From “Operation Mincemeat” - Charles Cholmondeley, left, and Ewen Montagu in April 1943, about to put their ruse in motion.

Excellent westerns have been composed by people who could barely ride a horse, and the best writers of sex scenes are often novelists you wouldn’t wish to see naked. But when it comes to spy fiction, life and art tend to collide fully: nearly all of the genre’s greatest practitioners worked in intelligence before signing their first book contract. “W. Somerset Maugham, John Buchan, Ian Fleming, Graham Greene, John le Carré: all had experienced the world of espionage firsthand,” Ben Macintyre writes in his new book, “Operation Mincemeat.” “For the task of the spy is not so very different from that of the novelist: to create an imaginary, credible world and then lure others into it by words and artifice.” Both are lurkers, confounders, ironists, betrayers: in a word, they’re spooks.

Mr. Macintyre himself writes about spies so craftily, and so ebulliently, that you half suspect him of being some type of spook himself. It is apparently not so. He is a benign-seeming writer at large and associate editor at The Times of London, a father of three and the author of five previous, respected nonfiction books, including “Agent Zigzag: A True Story of Nazi Espionage, Love, and Betrayal” (2007). Perhaps he is also controlling predator drones and a flock of assassins from a basement compound. But, alas, I doubt it.

“Operation Mincemeat” is utterly, to employ a dead word, thrilling. But to call it thus is to miss the point slightly, in terms of admiring it properly. Mr. Macintyre has got his hands around a true story that’s so wind-swept, so weighty and so implausible that the staff of a college newspaper, high on glue sticks, could surely take its basic ingredients and not completely muck things up.

I first read about this in David Ignatius's book, Body of Lies. That was after seeing the film with Leo DiCaprio. In turn, I went to the film, The man who never was, with Clifton Webb, and its eponymous book.

Excellent westerns have been composed by people who could barely ride a horse, and the best writers of sex scenes are often novelists you wouldn’t wish to see naked. But when it comes to spy fiction, life and art tend to collide fully: nearly all of the genre’s greatest practitioners worked in intelligence before signing their first book contract. “W. Somerset Maugham, John Buchan, Ian Fleming, Graham Greene, John le Carré: all had experienced the world of espionage firsthand,” Ben Macintyre writes in his new book, “Operation Mincemeat.” “For the task of the spy is not so very different from that of the novelist: to create an imaginary, credible world and then lure others into it by words and artifice.” Both are lurkers, confounders, ironists, betrayers: in a word, they’re spooks.

Mr. Macintyre himself writes about spies so craftily, and so ebulliently, that you half suspect him of being some type of spook himself. It is apparently not so. He is a benign-seeming writer at large and associate editor at The Times of London, a father of three and the author of five previous, respected nonfiction books, including “Agent Zigzag: A True Story of Nazi Espionage, Love, and Betrayal” (2007). Perhaps he is also controlling predator drones and a flock of assassins from a basement compound. But, alas, I doubt it.

“Operation Mincemeat” is utterly, to employ a dead word, thrilling. But to call it thus is to miss the point slightly, in terms of admiring it properly. Mr. Macintyre has got his hands around a true story that’s so wind-swept, so weighty and so implausible that the staff of a college newspaper, high on glue sticks, could surely take its basic ingredients and not completely muck things up.

I first read about this in David Ignatius's book, Body of Lies. That was after seeing the film with Leo DiCaprio. In turn, I went to the film, The man who never was, with Clifton Webb, and its eponymous book.

Labels:

Book review,

England,

Spying,

WW2

Tuesday, May 11, 2010

Capitalist democracy crisis

It is three years since the failure of two Bear Stearns hedge funds signaled the start of the biggest financial crisis since the Great Depression, and the air is thick with the sound of stable doors being shut long after the horses bolted. At some point this year a vast new picket fence will be built around the entire ranch, in the form of a new financial regulation act.

Both these [proposed legislation] measures recall the old British sitcom “Yes Minister,” in which all crises elicited the following response from the clueless politician Jim Hacker: “Something must be done. This is something. Therefore we must do it.” As Richard A. Posner argues in “The Crisis of Capitalist Democracy,” Congress is rushing to devise remedies for a crisis we have not yet properly understood. Indeed, the House bill explicitly commissions studies of the causes of the crisis while at the same time legislating to prevent its recurrence.

The Crisis of capitalist democracy

By Richard A. Posner

402 pp. Harvard University Press. $25.95

Posner is a man for all crises. Although he made his reputation as a specialist in antitrust law (he is a judge in the Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit and a senior lecturer at the University of Chicago Law School), he wrote extensively on the subject of terrorism and other cata strophic threats in the wake of the 9/11 attacks. His indefatigable intellect has been equally engaged by this new crisis. He has written one book, “A Failure of Capitalism,” at least 10 articles and umpteen blog posts on the subject. This latest volume is a plea for us to understand first and pass legislation later.

In Posner’s eyes, we are living through a second depression. The root causes were a failure of monetary policy (the Fed kept its short-term interest rate too low between 2001 and 2004), a failure of regulatory oversight (the Federal Reserve and the S.E.C. were “asleep at the switch”) and a failure of intellectual rigor (economists claimed that the enlightened self-interest of bankers and shareholders would suffice to prevent such a crisis).

Greenspan is at the top of the list of the responsible parties, surely. And it is a long list.

After the crisis began, matters were made much worse by the “colossal blunder” of allowing Lehman Brothers to fail. Happily, successive administrations responded by running huge fiscal deficits, a Keynesian remedy of which Posner wholeheartedly approves. Unhappily, the public became distracted by “demagoguery about executive salaries and perks,” which were not themselves a cause of the crisis. Worse, Congress began prematurely legislating to increase financial regulation, forgetting that “anything that limits the rights of creditors causes them to raise interest rates, thereby reducing economic activity.”

Excoriating fat cat bankers and Wall Street satisfies the blood lust of the populace, but diverts attention to what really matters: understanding what happened, then fixing the system. But demagoguery will not allow for time to be taken, for elections loom and the advantage must be taken now.

By directing their fire at bankers, Posner suggests, legislators want us to forget that among “the major culprits in our present economic distress” have been “government officials.” Moreover, the new regulations being discussed in Congress are tending to increase uncertainty in financial markets, another drag on recovery. More and more, the question is whether or not the United States is actually “governable” — hence “the crisis of capitalist democracy.”

Among, yes, among many.

A born-again Keynesian who remains an ardent opponent of big government, Posner may remind some readers of the two-headed pushmi-pullyu in the Doctor Dolittle books.

Seems a contradiction to oppose big government and favor deficit spending.

For Posner, the American system of government is “cumbersome, clotted, competence- challenged, even rather shady.” He confesses himself “perplexed by how government . . . has managed to escape most of the blame for our current economic state.” Well, maybe because his fellow Keynesians have relentlessly lauded government as the solution.

What nonsense, to blame government and Keynesians.

Otherwise, we should apply lessons that have already been learned in the realm of counterterrorism. We need more rotation of senior personnel among government financial agencies; better funding of those agencies; more pooling of intelligence between those agencies.

Real reform is opposed by Wall Street money, and it will be given to those who defend its interests.

Posner makes it clear that he understands the risks the United States now faces as the crisis of private finance continues its metamorphosis into a crisis of public finance: an exploding debt relative to gross domestic product; larger risk premiums as investors prepare for higher inflation or a weaker dollar; rising interest rates; a greater share of tax revenues going for interest payments; a diminishing share of resources available for national security as opposed to Social Security. “As an economic power,” Posner concludes, “we may go the way of the British Empire.” Indeed. It seems not to have struck the judge that British decline and the rise of Keynesianism went hand in hand.

Oy.

Both these [proposed legislation] measures recall the old British sitcom “Yes Minister,” in which all crises elicited the following response from the clueless politician Jim Hacker: “Something must be done. This is something. Therefore we must do it.” As Richard A. Posner argues in “The Crisis of Capitalist Democracy,” Congress is rushing to devise remedies for a crisis we have not yet properly understood. Indeed, the House bill explicitly commissions studies of the causes of the crisis while at the same time legislating to prevent its recurrence.

The Crisis of capitalist democracy

By Richard A. Posner

402 pp. Harvard University Press. $25.95

Posner is a man for all crises. Although he made his reputation as a specialist in antitrust law (he is a judge in the Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit and a senior lecturer at the University of Chicago Law School), he wrote extensively on the subject of terrorism and other cata strophic threats in the wake of the 9/11 attacks. His indefatigable intellect has been equally engaged by this new crisis. He has written one book, “A Failure of Capitalism,” at least 10 articles and umpteen blog posts on the subject. This latest volume is a plea for us to understand first and pass legislation later.

In Posner’s eyes, we are living through a second depression. The root causes were a failure of monetary policy (the Fed kept its short-term interest rate too low between 2001 and 2004), a failure of regulatory oversight (the Federal Reserve and the S.E.C. were “asleep at the switch”) and a failure of intellectual rigor (economists claimed that the enlightened self-interest of bankers and shareholders would suffice to prevent such a crisis).

Greenspan is at the top of the list of the responsible parties, surely. And it is a long list.

After the crisis began, matters were made much worse by the “colossal blunder” of allowing Lehman Brothers to fail. Happily, successive administrations responded by running huge fiscal deficits, a Keynesian remedy of which Posner wholeheartedly approves. Unhappily, the public became distracted by “demagoguery about executive salaries and perks,” which were not themselves a cause of the crisis. Worse, Congress began prematurely legislating to increase financial regulation, forgetting that “anything that limits the rights of creditors causes them to raise interest rates, thereby reducing economic activity.”

Excoriating fat cat bankers and Wall Street satisfies the blood lust of the populace, but diverts attention to what really matters: understanding what happened, then fixing the system. But demagoguery will not allow for time to be taken, for elections loom and the advantage must be taken now.

By directing their fire at bankers, Posner suggests, legislators want us to forget that among “the major culprits in our present economic distress” have been “government officials.” Moreover, the new regulations being discussed in Congress are tending to increase uncertainty in financial markets, another drag on recovery. More and more, the question is whether or not the United States is actually “governable” — hence “the crisis of capitalist democracy.”

Among, yes, among many.

A born-again Keynesian who remains an ardent opponent of big government, Posner may remind some readers of the two-headed pushmi-pullyu in the Doctor Dolittle books.

Seems a contradiction to oppose big government and favor deficit spending.

For Posner, the American system of government is “cumbersome, clotted, competence- challenged, even rather shady.” He confesses himself “perplexed by how government . . . has managed to escape most of the blame for our current economic state.” Well, maybe because his fellow Keynesians have relentlessly lauded government as the solution.

What nonsense, to blame government and Keynesians.

Otherwise, we should apply lessons that have already been learned in the realm of counterterrorism. We need more rotation of senior personnel among government financial agencies; better funding of those agencies; more pooling of intelligence between those agencies.

Real reform is opposed by Wall Street money, and it will be given to those who defend its interests.

Posner makes it clear that he understands the risks the United States now faces as the crisis of private finance continues its metamorphosis into a crisis of public finance: an exploding debt relative to gross domestic product; larger risk premiums as investors prepare for higher inflation or a weaker dollar; rising interest rates; a greater share of tax revenues going for interest payments; a diminishing share of resources available for national security as opposed to Social Security. “As an economic power,” Posner concludes, “we may go the way of the British Empire.” Indeed. It seems not to have struck the judge that British decline and the rise of Keynesianism went hand in hand.

Oy.

The Jewish Question

‘Trials of the Diaspora’

By ANTHONY JULIUS

Reviewed by HAROLD BLOOM

Anthony Julius’s fiercely relevant book on British anti-Semitism is particularly strong on Shylock, Fagin and the whole cavalcade of Jew-hatred in English literature.

Books About Martin Heidegger

By EMMANUEL FAYE and DANIEL MAIER-KATKIN

Reviewed by ADAM KIRSCH

Martin Heidegger was undeniably a Nazi. But was his affiliation an “escapade,” as Hannah Arendt claimed, or is his philosophy itself fundamentally corrupt? Two new books reconsider the question.

Irène Némirovsky’s Life and Stories

Reviewed by FRANCINE PROSE

A biography of Irène Némirovsky and a collection of her stories raise questions about her relationship to her Jewish roots.

The Man Who Broke Babe’s Record

Associated Press - Henry Aaron hit home run No. 715 on April 8, 1974, breaking Babe Ruth's record.

Off Al Downing. We were in the DC suburbs; it was a rainy day. Now that Barry Bonds has come along, carrying his steroids and his reputation, Hank Aaron seems a decent fellow who does deserve to replace the Babe as homerun king. It wasn't so in 1974: many people questioned his legitimacy in a number of different ways, ugliest of all racially.

I’m not sure what this says about America, or about publishing or baseball or sports writers, but it has taken 36 years for a proper full-dress biography of Henry Aaron, the man who, in 1974, broke Babe Ruth’s home run record, and did so as a black man playing for Major League Baseball’s first franchise in the Deep South. His is a great American life, and Howard Bryant’s “Last Hero: A Life of Henry Aaron” rises confidently to meet it.

Mr. Bryant’s book can be read as a companion piece, and a reply of sorts, to “Willie Mays: The Life, the Legend,” the recent biography by James S. Hirsch. These two ballplayers were both born in Alabama during the Great Depression (Mays in 1931, Aaron three years later), and both were among the last Hall of Famers to have played in the Negro Leagues. Their years on the field overlapped almost exactly. But they could not have been more different as personalities. Mays was joyous and electric, on the field and off, while Aaron was introverted, sometimes painfully so. They became lifelong, if low-key, antagonists.

A Life of Henry Aaron 796.3570 B or B Aaron

By Howard Bryant

Illustrated. 600 pages. Pantheon Books. $29.95.

Mr. Bryant, a senior writer for ESPN magazine, quotes the sportscaster Bob Costas as remarking, about Mays, that we “associate him with fun” and remember him with fondness. With Aaron, he added, “it is all about respect.” That quotation lingers like wood smoke over “The Last Hero.” These biographies of Mays and Aaron, taken together, are a striking and elegiac assessment of race relations in America during the 20th century. They are elegant portraits, as well, of two different ways of being a man. Wrap them both up for the 14-year-old in your life. The volume that’ll be left standing when the major book awards are handed out, though, is Mr. Bryant’s, I suspect. His is the brawny one, the one with serious and complicated swat.

Henry Aaron ... was a proud man who built and owned his own house, a rarity for African-Americans in Mobile at the time. Henry hated to see his father humiliated because of his race. He would watch, Mr. Bryant writes, “as his father was forced to surrender his place in line at the general store to any whites who entered.” Baseball seemed like a way out. Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color line in 1947, when Henry was 13. Henry, who idolized Robinson, began practicing relentlessly, hitting bottle caps with a stick when there was no other equipment around. In a typically perceptive line, Mr. Bryant writes, “Hitting, it could be argued, represented the first meritocracy in Henry’s life.”

Aaron was a loner and a mediocre student, and it’s unclear if he graduated from high school. “Henry would never answer the question directly,” Mr. Bryant writes. (Aaron cooperated with this biography, Mr. Bryant writes, even if he was “never overly enthusiastic” about it.) In 1952, when he was 18, he left home to join the Indianapolis Clowns in the Negro League, baseball’s equivalent of the Harlem Globetrotters. He played only a few games with them before joining the Milwaukee Braves farm system, ultimately playing in the South Atlantic League, better known at the Sally League. The Sally League operated in the Deep South, and Aaron was among its first black players, a breakthrough Mr. Bryant likens to that of Jackie Robinson’s. It was a difficult time for Aaron. When he left home, he had never been far outside of Mobile except on horseback. He had never had an extended conversation with a white person or been in a white person’s home. Suddenly fans were calling him “alligator bait” and telling him to “go back to the cotton fields.”

Aaron’s first season with the Milwaukee Braves was in 1954, and he led the team, which included the pitcher Warren Spahn, to the World Series twice, winning one, before he was 25. (He didn’t know then that he would never play in another.) He was criticized for his casual style, which some found to be lazy. He didn’t “move with the frothy enthusiasm and frightened eagerness of most rookies,” Mr. Bryant writes. One teammate began calling him Snowshoes because of his stiff-legged running style, and his manager likened him to Stepin Fetchit.

They got on Clemente's case also, because they didn't like his style. Now, of course, everyone loves him.

Word also spread, among some in the press, that Aaron, who was not comfortable speaking in public, was not overly bright. He chafed at these characterizations, and at what he saw as a lack of respect from his manager, who kept shifting his playing position and place in the batting order, something that never happened to other stars. It wasn’t until people began to realize that it was Aaron, and not Mays, who had a shot at breaking Babe Ruth’s home run record of 714 that they began really giving him his due.

Reluctantly, and some not at all. He was not given his due universally.

Mr. Bryant writes alertly about Aaron’s dogged pursuit of Ruth’s record with the mediocre Atlanta Braves, about the hate mail he received and about the hand-wringing from some pundits about whether he was a worthy heir to Ruth. He writes even more vividly about how Aaron has often seemed an enigma, failing to speak up loudly during the civil-rights era, and uttering evasive comments about Barry Bonds, who would break his home-run record in 2007, a record tainted by allegations of steroid use. “Baseball fans would call on him,” Mr. Bryant writes about Aaron, “and he would confuse them.”

Aaron is clearly a hard man to get to know, and I’m not sure Mr. Bryant entirely does. His life off the field is detailed haphazardly: his two marriages, his children, his passions. His own words, quoted here, are mostly unmemorable. But “The Last Hero: A Life of Henry Aaron” had the forceful sweep of a well-struck essay as much as that of a first-rate biography. In an era in which home runs are now a discredited commodity, Henry Aaron looms larger than ever: a nation has returned its lonely eyes to him.

Monday, May 10, 2010

Ghost town

Fairly good, certainly entertaining film. Ricky Gervais plays a dentist deliberately oblivious of anyone other than himself, to the point of arrogance. Greg Kinnear is an adulterer who is hit by a bus but is not released from the temporal world; his assignment is his wife, played by Téa Leoni, who, again, does good work. It occurred to me afterward that Leoni could handle meatier roles; in the two roles I've seen her, this one and in Fun with Dick and Jane, her role was not as filled out, as substantial, as the male lead

At one point it occurred to me that the film takes its direction from Ghost, with Patrick Swayze and Demi Moore. It works. I enjoyed it

At one point it occurred to me that the film takes its direction from Ghost, with Patrick Swayze and Demi Moore. It works. I enjoyed it

Saturday, May 8, 2010

Five Best Baseball Books

These baseball books belong in your reading lineup, says Peter Morris.

1. The Glory of Their Times. Lawrence S. Ritter. Macmillan, 1966. 796.357 R

Spurred by the death of baseball legend Ty Cobb in 1961, Lawrence Ritter, an economics professor, made it his mission to tape-record the memories of other players from Cobb's generation before these men were also gone. The result is an invaluable record of what it felt like to play big-league baseball in the early 20th century. Former New York Giants outfielder Fred Snodgrass, for instance, recalled what would happen when the umpire tossed out a new ball: Helpful infielders would throw the ball around a few times—until it came back to the pitcher "as black as the ace of spades. All the infielders were chewing tobacco or licorice, and spitting into their gloves, and they'd give that ball a good going over before it got to the pitcher." Eagle-eyed observers have detected some errors in the recollections, but that scarcely matters. Hundreds of baseball books get the minutiae right. None has ever captured the spirit of an era better than "The Glory of Their Times."

2. Baseball's Great Experiment. Jules Tygiel. Oxford, 1983. 796.3572 Robinson T

Jackie Robinson's re-integration of organized baseball after a half-century of tacit segregation remains the most remarkable chapter in the game's history. Yet the magnitude of Robinson's courage makes his story difficult to relate without rendering him a paragon of saintly virtue and the events of his life a pat melodrama. We are thus fortunate to have Jules Tygiel's thoughtful portrait of baseball's "great experiment." We see the disturbing broader context of racism in the sport, but we also encounter Robinson as a real person. Turning the other cheek did not come naturally to him: "With Jackie's temper being the way it was," recalled fellow Negro Leaguer Quincy Trouppe, "it didn't seem likely that a major league team would be willing to take a chance with him." Robinson emerges as an inspiring, entirely human hero whose triumph meant conquering his imperfections.

3. The End of Baseball as We Knew It. Charles Korr . University of Illinois, 2002. 331.8904 K

[331 - Labor Economics]

Mining the archives of the Major League Baseball Players Association might sound like an unpromising research project, but Charles Korr turned his findings into a compulsively readable book about how a submissive "house union" was transformed during the 1970s into a union with extraordinary power. For some, that revolution gave ballplayers their long-overdue fair share of the pie. Others saw it as baseball's apocalypse, turning players into rootless guns-for-hire and spoiled millionaires. Korr's splendid study may not sway the true believers in either camp, but it will furnish any reader with a better understanding of the events that shaped the free-agent era.

4. Dollar Sign on the Muscle. Kevin Kerrane. Beaufort, 1984. 796.35702 K

A baseball scout, in Kevin Kerrane's unforgettable portrait of the profession, is part traveling salesman, part spymaster and part hunter for that mythical creature known as "the arm behind the barn." Most of all, it seems, scouts—after all those hours of hanging around ballparks—are consummate storytellers. Kerrane shares their love of a good tale, and the result is a lyrical study of the world of baseball scouting. The 1965 arrival of the amateur draft changed the profession forever, replacing cloak-and-dagger tactics with bureaucracies. But the scouts in "Dollar Sign on the Muscle" are exhilarating to read about: No matter how many disappointments they endure, these men remain steadfast in their belief that the next phenom is just waiting to be discovered.

5. The Dickson Baseball Dictionary. Paul Dickson. Norton, 2009 (3rd ed.) R 796.357 D

Dictionaries aren't usually thought of as works of history, let alone as fun reads, yet "The Dickson Baseball Dictionary" manages against all odds to be both. With each new edition it evolves and expands—the recently released third edition includes more than 10,000 entries and sprawls to nearly a thousand pages. The authoritative entries make it a valuable guide to baseball terminology and history, but what really distinguishes this reference work is its sharp eye for telling anecdotes, apt quotations and succinct definitions. Lord Charles: "An appreciative name for a superb curveball, which elevates an Uncle Charlie to a regal level." The dictionary is itself royalty among baseball reference works.

—Mr. Morris is the author of "A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball." 796.357 M

1. The Glory of Their Times. Lawrence S. Ritter. Macmillan, 1966. 796.357 R

Spurred by the death of baseball legend Ty Cobb in 1961, Lawrence Ritter, an economics professor, made it his mission to tape-record the memories of other players from Cobb's generation before these men were also gone. The result is an invaluable record of what it felt like to play big-league baseball in the early 20th century. Former New York Giants outfielder Fred Snodgrass, for instance, recalled what would happen when the umpire tossed out a new ball: Helpful infielders would throw the ball around a few times—until it came back to the pitcher "as black as the ace of spades. All the infielders were chewing tobacco or licorice, and spitting into their gloves, and they'd give that ball a good going over before it got to the pitcher." Eagle-eyed observers have detected some errors in the recollections, but that scarcely matters. Hundreds of baseball books get the minutiae right. None has ever captured the spirit of an era better than "The Glory of Their Times."

2. Baseball's Great Experiment. Jules Tygiel. Oxford, 1983. 796.3572 Robinson T

Jackie Robinson's re-integration of organized baseball after a half-century of tacit segregation remains the most remarkable chapter in the game's history. Yet the magnitude of Robinson's courage makes his story difficult to relate without rendering him a paragon of saintly virtue and the events of his life a pat melodrama. We are thus fortunate to have Jules Tygiel's thoughtful portrait of baseball's "great experiment." We see the disturbing broader context of racism in the sport, but we also encounter Robinson as a real person. Turning the other cheek did not come naturally to him: "With Jackie's temper being the way it was," recalled fellow Negro Leaguer Quincy Trouppe, "it didn't seem likely that a major league team would be willing to take a chance with him." Robinson emerges as an inspiring, entirely human hero whose triumph meant conquering his imperfections.

3. The End of Baseball as We Knew It. Charles Korr . University of Illinois, 2002. 331.8904 K

[331 - Labor Economics]

Mining the archives of the Major League Baseball Players Association might sound like an unpromising research project, but Charles Korr turned his findings into a compulsively readable book about how a submissive "house union" was transformed during the 1970s into a union with extraordinary power. For some, that revolution gave ballplayers their long-overdue fair share of the pie. Others saw it as baseball's apocalypse, turning players into rootless guns-for-hire and spoiled millionaires. Korr's splendid study may not sway the true believers in either camp, but it will furnish any reader with a better understanding of the events that shaped the free-agent era.

4. Dollar Sign on the Muscle. Kevin Kerrane. Beaufort, 1984. 796.35702 K

A baseball scout, in Kevin Kerrane's unforgettable portrait of the profession, is part traveling salesman, part spymaster and part hunter for that mythical creature known as "the arm behind the barn." Most of all, it seems, scouts—after all those hours of hanging around ballparks—are consummate storytellers. Kerrane shares their love of a good tale, and the result is a lyrical study of the world of baseball scouting. The 1965 arrival of the amateur draft changed the profession forever, replacing cloak-and-dagger tactics with bureaucracies. But the scouts in "Dollar Sign on the Muscle" are exhilarating to read about: No matter how many disappointments they endure, these men remain steadfast in their belief that the next phenom is just waiting to be discovered.

5. The Dickson Baseball Dictionary. Paul Dickson. Norton, 2009 (3rd ed.) R 796.357 D