Showing posts with label US. Show all posts

Showing posts with label US. Show all posts

Saturday, June 29, 2013

Bridge at Remagen (1969)

Recommended by PN patron. George Segal emotes, does nice job as Army leiutenant leading a squad spearheading US advance across the Rhine. Ben Gazzara does good job as a cynical soldier who is, nevertheless, a crack shot and fearless. Robert Vaughn slightly overplays role as German major sent to hold the last standing bridge crossing the Rhine. Hitler has ordered the bridge to be blown up, even though that will strand 75,000 German soldiers. Despite efforts to hold bridge, an unofficial order given to vaughn's character by his commanding general, he finally decides to blow it up, only to hVe the dynamite he was sent for the jon turn out to ne defective. In next to last scene, Vaughn's major is shot by firing squad. Film tried to show war was more than just shooting, anticipating "Saving Private Ryan" by three decades. Very good war movie.

Labels:

Armed forces,

Germany,

US,

World War

Wednesday, November 14, 2012

Wednesday, October 24, 2012

Sunday, October 9, 2011

A bridge too far

Film version of Cornelius Ryan's book. Cast includes Dirk Bogarde, James Caan, Michael Caine, Sean Connery, and Edward Fox, as well as Elliot Gould, Laurence Olivier and Liv U. Not a happy story, but a good war movie.

Saturday, September 17, 2011

Man in the middle

Not quite sure why I picked out this film, but I have always liked Robert Mitchum. Here he plays an army lifer who gets called to a joint American-British theater during the Second World War (keeping with the theme of my currently reading H.W. Brands's biography of FDR, Traitor to his class), and is asked to provide a credible defense for a GI who has murdered a Brit in cold blood in front of numerous witnesses. Mitchum pays Lt. Col. Barney Adams; he has been summoned by General Kempton (played by another favorite, Barry Sullivan), a friend's of his father (an off-screen senior Adams). Col. Adams reluctantly accepts the assignment, and then pursues all leads, in order to provide a vigorous defense.

Adams refuses to accept what is obviously a coverup. Along the way he meets a nurse, Kate Davray (played by France Nuyen), who provides him with evidence he is, at first, reluctant to accept. What he is not reluctant to do is pursue Nurse Davray, in a 1963 sort of way.

There is much cigarette smoking, much alcohol drinking. Adams defiantly pursues a vigorous defense that even his client, played with a slightly too-heavy hand that almost descends to schtick by Keenan Wynn. Mitchum does a deft job of acting, and fully extends the role. Trevor Howard underplays a British psychiatrist who has been shunted to dispensing medicines, exiled from his true work. Cynical, Major Kensington comes to the rescue of Adams, whose every attempt to get at the truth is frustrated by roadblocks thrown in his way even by his sponsor, General Kempton.

Adams finally accepts Nurse Davray's evidence, and, along with Kensington's corroborating evidence, wins the case. Nicely done.

Adams refuses to accept what is obviously a coverup. Along the way he meets a nurse, Kate Davray (played by France Nuyen), who provides him with evidence he is, at first, reluctant to accept. What he is not reluctant to do is pursue Nurse Davray, in a 1963 sort of way.

There is much cigarette smoking, much alcohol drinking. Adams defiantly pursues a vigorous defense that even his client, played with a slightly too-heavy hand that almost descends to schtick by Keenan Wynn. Mitchum does a deft job of acting, and fully extends the role. Trevor Howard underplays a British psychiatrist who has been shunted to dispensing medicines, exiled from his true work. Cynical, Major Kensington comes to the rescue of Adams, whose every attempt to get at the truth is frustrated by roadblocks thrown in his way even by his sponsor, General Kempton.

Adams finally accepts Nurse Davray's evidence, and, along with Kensington's corroborating evidence, wins the case. Nicely done.

Monday, September 12, 2011

House of Bamboo

This all started with a column in a New Yorker issue in August, Critic's Notebook: Trouble in Mind. To wit: The most exciting spasm of violence in Samuel Fuller's wide-screen, color-splashed 1955 film noir, "House of Bamboo", is one that doesn't happen. It involves an American crime boss (Robert Ryan) who runs a syndicate in Tokyo, a hard-nosed expat (Robert Stack) who has recently joined the gang and arouses suspicion, and a billiard ball. In the first Hollywood feature to be shot on location in postwar Japan, Fuller transports to an exoticized setting his usual concern: the conflict between the moral repugnance of violence and its visual and visceral thrills. The movie is famous for its gunplay - a bathtub shooting that's sordidly funny, a police ambush of silhouettes seen through the rice paper screen, and a climactic shootout on a flying-saucer-like carousel perched on a rooftop high above the city. But for one terrifying moment, captured in a single tense shot and embodied in Ryan's seething, panterish self-control, Fuller makes his fierce sympathies ambiguous even as he imagines gore beyond what Hollywood mores allowed - and hints that he enjoyed it. The writer was Richard Brody.

In watching the commentary provided by two critics, several names jumped out:

The street with no name

Pickup on South Street

I shot Jesse James

Cinemascope

The film itself was interesting. It begins with a narration, which itself is unusual: a film, not a documentary, begins as if it were a documentary. It is post-WW2 Japan. A supply train chugs along, and stops for a peasant struggling to move his oxen off the tracks. In quick order, it turns out he is not a peasant, for he chokes the engineer who comes out to yell at him. Other train personnel are similarly mugged. And the lone US soldier is shot, and killed. A peasant woman hears the shot, rushes over, sees the dead body, and screams into the camera.

Robert Stack lands in Yokohama, takes a taxi to Tokyo, and chases after Mariko, the sweetheart of his buddy (who in prior shots is seen on an operating table being interrogated by US Army personnel, who find the picture of Mariko in his wallet; he confesses that they were married, but that it is a secret). Stack's character (Spanier) begins to intimidate pachinko managers, shaking them down for protection money. At the second joint he is ambushed by men working for Ryan's character (Sandy). He is thrown through rice paper screens, and beat up a bit. In short order, he joins the gang, and becomes a favorite of the boss. Such favoritism rankles Sandy's long-standing second-in-command, and tension is born, to manifest itself in various ways (including the above-mentioned bathtub scene).

In watching the commentary provided by two critics, several names jumped out:

The street with no name

Pickup on South Street

I shot Jesse James

Cinemascope

The film itself was interesting. It begins with a narration, which itself is unusual: a film, not a documentary, begins as if it were a documentary. It is post-WW2 Japan. A supply train chugs along, and stops for a peasant struggling to move his oxen off the tracks. In quick order, it turns out he is not a peasant, for he chokes the engineer who comes out to yell at him. Other train personnel are similarly mugged. And the lone US soldier is shot, and killed. A peasant woman hears the shot, rushes over, sees the dead body, and screams into the camera.

Robert Stack lands in Yokohama, takes a taxi to Tokyo, and chases after Mariko, the sweetheart of his buddy (who in prior shots is seen on an operating table being interrogated by US Army personnel, who find the picture of Mariko in his wallet; he confesses that they were married, but that it is a secret). Stack's character (Spanier) begins to intimidate pachinko managers, shaking them down for protection money. At the second joint he is ambushed by men working for Ryan's character (Sandy). He is thrown through rice paper screens, and beat up a bit. In short order, he joins the gang, and becomes a favorite of the boss. Such favoritism rankles Sandy's long-standing second-in-command, and tension is born, to manifest itself in various ways (including the above-mentioned bathtub scene).

Tuesday, October 26, 2010

La Misma Luna

I wasn't sure if this would work for me, what with the pretty face and all, but I was surprised by it. This is a good movie. Mexicans crossing a river are found by the Migra, and some are separated from the rest of the group. A small boy lives back in his Mexican home, his mother winds up in East LA. He's cared for by his abuelita, and gets a phone call from his mother every Sunday morning at 10. When his abuelita dies, Carlitos decides he'll go and find his mother. He's shown helping a woman who is a sort of broker {Doña Carmen 'La Coyota' } for those hoping to cross the border. That is a topic that is not discussed anywhere, that I know.

Going to a young couple who had contacted Doña Carmen, offering to smuggle peopleacross the border, as they are US citizens, Carlos pays them to smuggle him across. but they are stopped at the border, their nervousness giving them away. Cleared, they go, only to be stopped, and their car impounded, as they have outstanding tickets.

Carlitos loses his money, is almost sold to a child pornographer or pimp, and is rescued by Reyna, a woman who feeds Mexicanaborers who need the help. This is also a topic not commonly discussed; in fact, both are (and aren't).

The movie is a bit of a tear-jerker, and melodramatic, but it works. It is well made, the story flows, and I enjoyed it a lot.

Going to a young couple who had contacted Doña Carmen, offering to smuggle peopleacross the border, as they are US citizens, Carlos pays them to smuggle him across. but they are stopped at the border, their nervousness giving them away. Cleared, they go, only to be stopped, and their car impounded, as they have outstanding tickets.

Carlitos loses his money, is almost sold to a child pornographer or pimp, and is rescued by Reyna, a woman who feeds Mexicanaborers who need the help. This is also a topic not commonly discussed; in fact, both are (and aren't).

The movie is a bit of a tear-jerker, and melodramatic, but it works. It is well made, the story flows, and I enjoyed it a lot.

Labels:

Mexicans,

Mexico,

Migrants,

US,

US-Mexico border

Wednesday, August 11, 2010

Friday, August 6, 2010

Soccer explains world

Foer, Franklin. (2004). How soccer explains the world: an unlikely theory of globalization. New York: HarperCollins.

Fascinating, enjoyable book.

“Thanks to the immigration of Africans and Asians, Jews have been replaced as the primary objects of European hate.” p.71

Fascinating, enjoyable book.

“Thanks to the immigration of Africans and Asians, Jews have been replaced as the primary objects of European hate.” p.71

Saturday, June 12, 2010

Yalta: the price of peace. (2010). Plokhy, Serhii

New York: Viking .

Various links include an event at the Woodrow Wilson Center, a segment on BookTV,

New York: Viking .

Various links include an event at the Woodrow Wilson Center, a segment on BookTV,

Saturday, May 15, 2010

Books on Statesmen

Evan Thomas chooses distinguished books on statesmen

1. Present at the Creation. Dean Acheson. Norton, 1969. [327.73 A (International Relations) and 973.918 A (North American history)]

Most people, when they are in the midst of history being made, are too caught up in the moment to see its larger meaning. Not the great American statesman Dean Acheson: His aptly named autobiography captures the precise date, on Feb. 27, 1947, when the duties of Pax Britannica passed to Pax Americana. Britain on that day told the U.S. that the British were no longer able to help protect Turkey and Greece from Soviet expansion; America was on its own. "We drank a martini or two to the confusion of our enemies," recorded Acheson, who would go on to become secretary of state (1949-53). Written with grandeur, verve and a certain puckish delight, "Present at the Creation" is the frankest and most gripping work by a statesman since Ulysses S. Grant's 1885 autobiography.

Grant's work is magnificent.

2. Passionate Sage . Joseph Ellis. Norton, 1993. 973.4409 E

Over the past decade or so, the best-seller lists have included some big and wonderfully readable biographies of the Founders, but the best portrait of a Revolutionary-era statesman is this slim, dense and relatively little known volume about John Adams. Written by Joseph Ellis before his own blockbuster biographies of Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, "Passionate Sage" is structured thematically. It demands a reader's close attention, but the reward is great. Ellis shows that Adams was able to use his shrewd understanding of human vanity, especially his own, to shape a government system of checks and balances. Ellis has fun with the irrepressible Adams, who like his old friend and rival Jefferson was obsessed with his place in history. "I thought my Books, as well as myself, were forgotten," Adams joked to Jefferson in 1813. "But behold! I am to become a great Man in my expiring moments."

3. Master of the Senate. Robert A. Caro. Knopf, 2002. B Johnson C

The United States Senate is, generally speaking, a boring place. On most days the chamber is empty, or a single senator drones on as others wander in and out. Yet Robert Caro—researching "Master of the Senate," the third volume in his magisterial series "The Years of Lyndon Johnson"—sat day after day high in the public galleries, conjuring the drama of an earlier time when giants, or one particular giant, strode the Senate floor. Caro's LBJ cajoles, whines, blusters, deceives, intimidates—and gets the Senate, still dominated in the 1950s by Southern Democrats, to pass the first-ever civil-rights bill. Johnson is crude, to put it mildly—Caro describes him on a "monument of a toilet," browbeating secretaries, assistants and other lawmakers. But if only we had someone like LBJ in Congress today.

4. The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt. Edmund Morris. Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, 1979. B Roosevelt M

Edmund Morris virtually inhabits his subject in "The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt" (the first book in a three-volume series that will conclude later this year). His feel for Roosevelt—a bragging, bullying, bellowing, yet somehow tender and always steadfast young man—is so tactile that it verges on the sensuous. "He was dubbed 'The Chief of the Dudes,' and satirized as a tight-trousered snob given to sucking the knob of his ivory cane," Morris writes. This volume, about the pre-presidential Roosevelt, is more engaging than the one that followed. Presidential biographies are almost inherently heavy going because presidents must always be doing too many things at once. But Morris, like TR, is never dull.

5. The Proud Tower. Barbara Tuchman. Macmillan, 1962. 901.941 T (also 909.82, and 940.28, and 940.311)

The turn of the 20th century was a great age of statesmen, or so it seemed. Dressed handsomely in frock coats, cutaways and top hats, they gravely, pompously, naïvely held international conferences that vowed to put an end to war, forever. Reading Barbara Tuchman's collection of elegant, elegiac essays about this period, you can almost hear the ice cracking beneath their feet. (The title comes from an Edgar Allan Poe poem, "While from a proud tower in the town / Death looks gigantically down.") One portrait is particularly captivating: the tragedy of Thomas Brackett Reed, the House speaker who tried to stop America from lunging into the race for empire in the last years of the 19th century. Reed was brilliant and indomitable, but he was unable to stand in the way of the lust for conquest and dominion that seized America and much of the civilized world on the eve of World War I.

—Mr. Thomas is the author of The war lovers : Roosevelt, Lodge, Hearst, and the rush to empire, 1898. 973.891 T

Printed in The Wall Street Journal, page W8

1. Present at the Creation. Dean Acheson. Norton, 1969. [327.73 A (International Relations) and 973.918 A (North American history)]

Most people, when they are in the midst of history being made, are too caught up in the moment to see its larger meaning. Not the great American statesman Dean Acheson: His aptly named autobiography captures the precise date, on Feb. 27, 1947, when the duties of Pax Britannica passed to Pax Americana. Britain on that day told the U.S. that the British were no longer able to help protect Turkey and Greece from Soviet expansion; America was on its own. "We drank a martini or two to the confusion of our enemies," recorded Acheson, who would go on to become secretary of state (1949-53). Written with grandeur, verve and a certain puckish delight, "Present at the Creation" is the frankest and most gripping work by a statesman since Ulysses S. Grant's 1885 autobiography.

Grant's work is magnificent.

2. Passionate Sage . Joseph Ellis. Norton, 1993. 973.4409 E

Over the past decade or so, the best-seller lists have included some big and wonderfully readable biographies of the Founders, but the best portrait of a Revolutionary-era statesman is this slim, dense and relatively little known volume about John Adams. Written by Joseph Ellis before his own blockbuster biographies of Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, "Passionate Sage" is structured thematically. It demands a reader's close attention, but the reward is great. Ellis shows that Adams was able to use his shrewd understanding of human vanity, especially his own, to shape a government system of checks and balances. Ellis has fun with the irrepressible Adams, who like his old friend and rival Jefferson was obsessed with his place in history. "I thought my Books, as well as myself, were forgotten," Adams joked to Jefferson in 1813. "But behold! I am to become a great Man in my expiring moments."

3. Master of the Senate. Robert A. Caro. Knopf, 2002. B Johnson C

The United States Senate is, generally speaking, a boring place. On most days the chamber is empty, or a single senator drones on as others wander in and out. Yet Robert Caro—researching "Master of the Senate," the third volume in his magisterial series "The Years of Lyndon Johnson"—sat day after day high in the public galleries, conjuring the drama of an earlier time when giants, or one particular giant, strode the Senate floor. Caro's LBJ cajoles, whines, blusters, deceives, intimidates—and gets the Senate, still dominated in the 1950s by Southern Democrats, to pass the first-ever civil-rights bill. Johnson is crude, to put it mildly—Caro describes him on a "monument of a toilet," browbeating secretaries, assistants and other lawmakers. But if only we had someone like LBJ in Congress today.

4. The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt. Edmund Morris. Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, 1979. B Roosevelt M

Edmund Morris virtually inhabits his subject in "The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt" (the first book in a three-volume series that will conclude later this year). His feel for Roosevelt—a bragging, bullying, bellowing, yet somehow tender and always steadfast young man—is so tactile that it verges on the sensuous. "He was dubbed 'The Chief of the Dudes,' and satirized as a tight-trousered snob given to sucking the knob of his ivory cane," Morris writes. This volume, about the pre-presidential Roosevelt, is more engaging than the one that followed. Presidential biographies are almost inherently heavy going because presidents must always be doing too many things at once. But Morris, like TR, is never dull.

5. The Proud Tower. Barbara Tuchman. Macmillan, 1962. 901.941 T (also 909.82, and 940.28, and 940.311)

The turn of the 20th century was a great age of statesmen, or so it seemed. Dressed handsomely in frock coats, cutaways and top hats, they gravely, pompously, naïvely held international conferences that vowed to put an end to war, forever. Reading Barbara Tuchman's collection of elegant, elegiac essays about this period, you can almost hear the ice cracking beneath their feet. (The title comes from an Edgar Allan Poe poem, "While from a proud tower in the town / Death looks gigantically down.") One portrait is particularly captivating: the tragedy of Thomas Brackett Reed, the House speaker who tried to stop America from lunging into the race for empire in the last years of the 19th century. Reed was brilliant and indomitable, but he was unable to stand in the way of the lust for conquest and dominion that seized America and much of the civilized world on the eve of World War I.

—Mr. Thomas is the author of The war lovers : Roosevelt, Lodge, Hearst, and the rush to empire, 1898. 973.891 T

Printed in The Wall Street Journal, page W8

Labels:

American history,

US,

War,

WW1,

WW2

Sunday, April 25, 2010

A Time to Remember

The Publisher. Alan Brinkley. Knopf, 531 pages, $35

Luce is one of the original 20th century right-wing blowhards who used his position in the media to push not objectivity but his own agenda. He did hire Margaret Bourke-White to shoot photogrpahs he included in Fortune magazine from its very beginning; her photogrpahs were also prominently published in Life magazine for many years.

Alan Brinkley's "The Publisher: Henry Luce and His American Century" marshals all the material for a devastating portrait of Luce as a bombastic, autocratic press lord who was full of idolatry for "Great Men" like Chiang Kai-shek and Gen. Douglas MacArthur and who made his magazines mouthpieces for his own ideology and obsessions. Instead, Mr. Brinkley has told Luce's saga with scrupulous fairness, compelling detail and more than a tinge of affection for his vast ambitions and vexing frailties. The author chronicles how Luce built the spindly Time into the world's greatest media empire of its era, with influence unmatched by any other American magazine. Still, Luce emerges as a man of manic energies and enthusiasms who, for all his fervent yearning to do good, bent the journalism of his magazines to propagandize for dubious crusades, most famously urging the "unleashing" of Chiang in the late 1940s to recapture a China lost to communism.

That was the sort of myth that the right wing of the Republican and Democratic parties used for years to bludgeon President Truman, FDR's memory and legacy, and subsequent Democrats: that they had lost China, as if it was for the US toi keep or lose.

at a "Turkish ball" at the Waldorf-Astoria in 1934, he met Clare Boothe, the bright, beautiful daughter of a kept woman, and Luce had a coup de foudre. For all his righteous scruples, he dumped his wife of more than a decade and mother of his children, embarking on a tempestuous marriage with Clare that lasted until his death in 1967. They competed with each other, cheated on each other, tormented each other and nearly divorced a dozen times.

[coup de foudre: a thunderbolt; a sudden, intense feeling of love.]

Perhaps it is from this man who ignored his own "righteous scruples" that Rudolf Guiliani learned the trick of dumping his wife and mother of his children for another woman. And after such effrontery to the morality they so busily lectured others on, and after violating its very basic tenets, they continued to appear in public without the least show of shame.

Mr. Brinkley, who teaches American history at Columbia University, neatly captures the tone of the couple's skyscraper-in-the-clouds idyll. Luce once bragged to Clare, the author of "The Women" and onetime U.S. ambassador to Italy, that he couldn't think of anyone who was his intellectual superior. Clare replied: What about Einstein? Well, countered Harry, Einstein was "a specialist."

Modet, too.

Clare had proposed a picture magazine called Life to Condé Nast—the man, not his company—when she worked as the managing editor of his Vanity Fair in the early 1930s. Luce had the same idea, and the triumph of Life gave him an unmatched pulpit where he could preach his increasingly right-wing vision for the U.S. and the world.

What a bully pulpit, too.

It was Luce's impatience with Franklin Roosevelt's tip-toeing into the war before Pearl Harbor that spurred him to take an active role in presidential politics. He fell hard for the Republican Wendell Willkie in 1940 and made his magazines such partisans of every successive GOP candidate for the White House that many of his editors despaired. Time Inc. magazines not only liked Ike, they slobbered over him. Luce did respect John F. Kennedy (although he backed Nixon) and succumbed to Lyndon Johnson's transparent flattery. An old-school anti-communist, Luce had "a strong distaste" for Joseph McCarthy, Mr. Brinkley writes, as a "crude and coarse man" whose "excesses threatened to discredit more legitimate anti-Communist activities," and the publisher never warmed up to Barry Goldwater's frontier conservatism.

Well, nt altogether a distasteful man, at any rate.

Mr. Brinkley has told the cautionary tale of the Luce Half-Century with the rigor, honesty and generosity that Luce's own magazines too often sacrificed to the proprietor's enormous ego and will to power.

Labels:

China,

Finance,

Journalism,

Media,

Photography,

US,

US History

Friday, April 16, 2010

An Independent Spirit

In her novels and short stories—and in her life as well—Muriel Spark's ferocity was as evident as her originality

Muriel Spark occupies a puzzling space in the pantheon of 20th-century writers. Undoubtedly great, she resists classification. Even a question as reductive as "Is she a major or a minor novelist?" dissolves into clouds of qualification. Some might argue that she is "major" in her intellectual reach or the power of her prose but "minor" in the heft of her novels—most of them are fewer than 200 pages long. But is Alberto Giacometti a minor artist because his sculptures are so thin?

Muriel Spark occupies a puzzling space in the pantheon of 20th-century writers. Undoubtedly great, she resists classification. Even a question as reductive as "Is she a major or a minor novelist?" dissolves into clouds of qualification. Some might argue that she is "major" in her intellectual reach or the power of her prose but "minor" in the heft of her novels—most of them are fewer than 200 pages long. But is Alberto Giacometti a minor artist because his sculptures are so thin?

Monday, April 12, 2010

Books on Guilt

One is a series of "Five Best" columns that appear at the weenekd in the WSJ. In this one Pascal Bruckner confesses his admiration of these books about guilt.

1. The Trial. Franz Kafka. Knopf, 1937.

One morning Joseph K. is arrested for no reason at all, brought before a court and, eventually, executed in a quarry: His ordeal has become a poignant metaphor for the experience of citizens in totalitarian regimes. In the eyes of the ruthless judicial system in Franz Kafka's "The Trial," Joseph K. is guilty of existing, no more than that; his crime is the very fact that he is alive. Nothing he can do can save him once he has fallen into the hands of the judges. The more he protests his innocence, the more he arouses suspicion. "Innocent of what?" one judge asks. "The Trial" (first published in German in 1925) is terrifying because the hero, without understanding why, begins collaborating with the machine that crushes him. One is reminded of the people convicted during the Moscow purge trials of the 1930s when they shouted, as they were about to be executed: "Long live Stalin! Long live the proletarian revolution!"

2. And Then There Were None. Agatha Christie. Dodd, Mead. 1940.

Ten people who have nothing in common find themselves on Indian Island. They have been invited there by a mysterious Mr. Owen, who has, unfortunately, not shown up. A couple of servants see to their comfort. On the living-room table the guests find 10 Indian statuettes, and in the bedrooms hangs a nursery rhyme announcing how each guest is to be murdered. The deaths follow one another implacably, hewing to the poem's predictions as though the characters' fates were foreordained. Everyone has sinned enough to deserve death; everyone bears the mark of Cain. Within this Puritan framework Agatha Christie displays her passion for playing with crime. As it turns out, one of the 10 guests is the murderer—and he knocks himself off as well, using a sophisticated technique to make it seem as if he has been killed by someone else. Christie's taste for trickery is stronger than her taste for punishment. Thus there is no tragedy in her work: Evil can always be overcome by a shrewd detective.

3. Heart of Darkness. Joseph Conrad. 1902.

In Joseph Conrad's "Heart of Darkness," an officer in the British merchant marine named Marlow sails up a serpentine African river to look for Kurtz, an ivory-trader from whom no word has been had for months. As Marlow ventures into the interior, oppressed by the dense jungle, he hears a strange report: In a mad quest for ivory, Kurtz has begun slaughtering the natives. Conrad took his inspiration from the atrocities committed by the Belgian King Leopold II, who was then master of the Congo and who tortured and massacred his recalcitrant subjects. Kurtz, of whom we get only glimpses, is fascinating because he speaks the language of the tormentor, not that of civilization: He feels no remorse; he is a man who never feels guilty. A pamphlet he has written on civilizing the natives ends with the terrible words: "Exterminate all the brutes!" He weaves a bond between the logic of profit and the logic of annihilation. Conrad's genius consists not solely in denouncing colonialism but also in anticipating the disasters that followed decolonization. We can read this short novel as a still-relevant depiction of the abominations that have stained the recent history of Africa.

4. The Fall. Albert Camus. Vintage. 1956.

At the height of the Cold War and communist domination over the French intelligentsia, Albert Camus published "The Fall," the brief confession of a "judge-penitent" named Clamens, who let a young woman commit suicide before his eyes by throwing herself into the Seine and did nothing to help her. Clamens has taken refuge in Amsterdam, preferring the canals' still water to the Seine's impetuous flow, and he likes to confide in strangers. He tells them that he does not regret what he has done—and then forces the strangers to confess, in turn, a crime of their own. I am a bastard, he seems to say, but so are you. Clamens practices public confession as kind of contamination, a way of implicating all humanity in his crime. The novel was an indirect attack on Jean-Paul Sartre, who was always ready to flagellate himself for being a bourgeois and to accuse France and Europe of causing all the world's ills. In the tradition of the 17th-century French moralists, Camus, concealed under this penitent's habit, denounces the moral hypocrisy of a certain kind of leftist.

5. The Human Stain. Philip Roth. Houghton Mifflin. 2000.

Coleman Silk has been forced to retire from his professorship amid murky accusations of racism, an episode in which he lost everything—his job, his family, his reputation. Embittered, he visits his new neighbor, the writer Nathan Zuckerman, to suggest that Zuckerman avenge him by writing his story. We discover that Silk's main crime is having tried to escape the racial prison in which America incarcerates its citizens: Born black, Silk has passed himself off as a Jew to escape the stereotypes he might have had to endure. Refusing to accept being identified by the color of his skin is, of course, an offense that Silk's "tolerant" colleagues find intolerable.

—Mr. Bruckner is the author of "The Tears of the White Man" (1986) and "The Tyranny of Guilt," recently published by Princeton University Press. Printed in The Wall Street Journal, page W8

1. The Trial. Franz Kafka. Knopf, 1937.

One morning Joseph K. is arrested for no reason at all, brought before a court and, eventually, executed in a quarry: His ordeal has become a poignant metaphor for the experience of citizens in totalitarian regimes. In the eyes of the ruthless judicial system in Franz Kafka's "The Trial," Joseph K. is guilty of existing, no more than that; his crime is the very fact that he is alive. Nothing he can do can save him once he has fallen into the hands of the judges. The more he protests his innocence, the more he arouses suspicion. "Innocent of what?" one judge asks. "The Trial" (first published in German in 1925) is terrifying because the hero, without understanding why, begins collaborating with the machine that crushes him. One is reminded of the people convicted during the Moscow purge trials of the 1930s when they shouted, as they were about to be executed: "Long live Stalin! Long live the proletarian revolution!"

2. And Then There Were None. Agatha Christie. Dodd, Mead. 1940.

Ten people who have nothing in common find themselves on Indian Island. They have been invited there by a mysterious Mr. Owen, who has, unfortunately, not shown up. A couple of servants see to their comfort. On the living-room table the guests find 10 Indian statuettes, and in the bedrooms hangs a nursery rhyme announcing how each guest is to be murdered. The deaths follow one another implacably, hewing to the poem's predictions as though the characters' fates were foreordained. Everyone has sinned enough to deserve death; everyone bears the mark of Cain. Within this Puritan framework Agatha Christie displays her passion for playing with crime. As it turns out, one of the 10 guests is the murderer—and he knocks himself off as well, using a sophisticated technique to make it seem as if he has been killed by someone else. Christie's taste for trickery is stronger than her taste for punishment. Thus there is no tragedy in her work: Evil can always be overcome by a shrewd detective.

3. Heart of Darkness. Joseph Conrad. 1902.

In Joseph Conrad's "Heart of Darkness," an officer in the British merchant marine named Marlow sails up a serpentine African river to look for Kurtz, an ivory-trader from whom no word has been had for months. As Marlow ventures into the interior, oppressed by the dense jungle, he hears a strange report: In a mad quest for ivory, Kurtz has begun slaughtering the natives. Conrad took his inspiration from the atrocities committed by the Belgian King Leopold II, who was then master of the Congo and who tortured and massacred his recalcitrant subjects. Kurtz, of whom we get only glimpses, is fascinating because he speaks the language of the tormentor, not that of civilization: He feels no remorse; he is a man who never feels guilty. A pamphlet he has written on civilizing the natives ends with the terrible words: "Exterminate all the brutes!" He weaves a bond between the logic of profit and the logic of annihilation. Conrad's genius consists not solely in denouncing colonialism but also in anticipating the disasters that followed decolonization. We can read this short novel as a still-relevant depiction of the abominations that have stained the recent history of Africa.

4. The Fall. Albert Camus. Vintage. 1956.

At the height of the Cold War and communist domination over the French intelligentsia, Albert Camus published "The Fall," the brief confession of a "judge-penitent" named Clamens, who let a young woman commit suicide before his eyes by throwing herself into the Seine and did nothing to help her. Clamens has taken refuge in Amsterdam, preferring the canals' still water to the Seine's impetuous flow, and he likes to confide in strangers. He tells them that he does not regret what he has done—and then forces the strangers to confess, in turn, a crime of their own. I am a bastard, he seems to say, but so are you. Clamens practices public confession as kind of contamination, a way of implicating all humanity in his crime. The novel was an indirect attack on Jean-Paul Sartre, who was always ready to flagellate himself for being a bourgeois and to accuse France and Europe of causing all the world's ills. In the tradition of the 17th-century French moralists, Camus, concealed under this penitent's habit, denounces the moral hypocrisy of a certain kind of leftist.

5. The Human Stain. Philip Roth. Houghton Mifflin. 2000.

Coleman Silk has been forced to retire from his professorship amid murky accusations of racism, an episode in which he lost everything—his job, his family, his reputation. Embittered, he visits his new neighbor, the writer Nathan Zuckerman, to suggest that Zuckerman avenge him by writing his story. We discover that Silk's main crime is having tried to escape the racial prison in which America incarcerates its citizens: Born black, Silk has passed himself off as a Jew to escape the stereotypes he might have had to endure. Refusing to accept being identified by the color of his skin is, of course, an offense that Silk's "tolerant" colleagues find intolerable.

—Mr. Bruckner is the author of "The Tears of the White Man" (1986) and "The Tyranny of Guilt," recently published by Princeton University Press. Printed in The Wall Street Journal, page W8

Friday, March 5, 2010

World Safe for Capitalism

The topic of books on the Dominican Republic arose last night; there are very few in the County. Peninsula owns two, from 1968 and 1970. There are nine all told in the County, which is pitiful. One is from 1928, written by Sumner Welles. (Look at his Wiki page; there is video from 1933). The books go to 1972, and then there is a jump to a book from 2002, A world safe for capitalism : dollar diplomacy and America's rise to global power. Reviews of that book mention the San Domingo Improvement Company. Googling that gave this as the first result: San Domingo Improvement Company Claims (Dominican Republic, United ... a pdf from the UN entitled REPORTS OF INTERNATIONAL ARBITRAL AWARDS. Why the UN? It's dated14 July 1904. Curious.

Interest piqued, I looked some more; the fourth link is for Ulises Heureau, president of the DR thrice in the 1880s. Fascinating reading. Mentioned is made of the Ten Years' War, one of three wars for Cuban independence.

Book sources Wikipedia page

Interest piqued, I looked some more; the fourth link is for Ulises Heureau, president of the DR thrice in the 1880s. Fascinating reading. Mentioned is made of the Ten Years' War, one of three wars for Cuban independence.

Book sources Wikipedia page

Labels:

Cuba,

Dominican Republic,

Spain,

US

Saturday, February 20, 2010

Valley of Death

The French Connection - Vietnam lessons the U.S. might have learned at Dien Bien Phu

Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

French paratroopers landing at Dien Bien Phu in November 1953.

In November 1953, France was in its eighth year of war for control over Indochina. Things were going poorly—Vietnamese guerrillas, or Vietminh, held the upper hand—and at a strategy session in Saigon the French commander, Gen. Henri Navarre, outlined his latest plan. "I'm thinking of occupying the basin of Dien Bien Phu," he began. "The goal of this risky operation will be to defend Laos." He went on to argue that the move would draw the Vietminh into a battle they could not win. France had the advantage of air power. A base at Dien Bien Phu—in the northwest corner of Vietnam, near the Laos border—could be resupplied by air, while guerrilla leader Ho Chi Minh's cadres would be forced to move huge numbers of men and matériel through miles of mountain jungle. Finishing his presentation, Gen. Navarre turned to the group. "What do you think?"

The politicians were onboard—but the officers balked. The military men were "unanimous in objection," one senior officer noted. Building a base in a mountain valley, they told Gen. Navarre, presented formidable challenges. Dropping in paratroopers would be dangerous, resupplying the base difficult, and Dien Bien Phu would drain manpower from more important theaters—all for questionable military gain. Nevertheless, Gen. Navarre got his base. Within months—on May 7, 1954, to be exact—Dien Bien Phu was overrun by the Vietminh. Two years later Gen. Navarre was rewriting history in his memoir of the war. "No unfavorable opinion," he wrote, "was expressed before the battle."

The annals of warfare are of course studded with questionable military decisions and after-battle lies, but for sheer hubris and incompetence it is hard to match what happened before and during the 56-day battle for Dien Bien Phu. Ted Morgan's "Valley of Death" is an authoritative account of those days—but it's also a history of the early U.S. involvement in Indochina. "The words Dien Bien Phu," President Dwight Eisenhower told a conference of newspaper publishers in April 1954, "are no longer just a funny-sounding name to be dismissed from the breakfast conversation because we don't know where it is." Indeed, by then Dien Bien Phu was proving a disaster for the French—one that held warning signs for the U.S.

A lesson not heeded.

Nearly every French assumption would be punctured that spring. None proved more disastrous than Gen. Navarre's faith in the power of air supremacy. The Vietnamese, led by the brilliant general Vo Nguyen Giap (whom the Americans would face a decade later), moved a seemingly limitless supply of men and munitions through the jungle to Dien Bien Phu. It was a mind-bending feat, and it gave the Vietminh high ground above the French base. In a memorable analysis, Ho Chi Minh turned a helmet upside down, pointed to the bottom and said: "That's where the French are." Fingering the helmet's rim, he added, "that's where we are. They will never get out."

Air power was held to be a significant advantage by US politicians and generals, and the Vietminh, relabeled Viet Cong and North Vietnamese, flouted as inferior.

Ho was right—and his forces held other advantages. China sent the Vietminh food, medicine and heavy weaponry. As a guerrilla force, the Vietminh enjoyed the edge in motivation and in knowledge of terrain. As Mr. Morgan writes: "The French had an air force. The Vietminh had home-field advantage and could count on the support of the rural population."

In the meantime, French blunders multiplied. France's commissioner general for Indochina was "better known for his champagne dinners in Saigon than his military knowledge." As soldiers died waiting for fresh supplies of food and medicine, parachute teams were delayed because they lacked training certificates. All the while, horrors accumulated on the battlefield. Wounded men languished in overcrowded wards; trenches filled with corpses; monsoon rains flooded the French camp. As conditions deteriorated, evacuation became nearly impossible. Mr. Morgan draws a stirring portrait of the French medic Paul Grauwin, who worked in soaked-through, maggot-infested tents handling "an unending procession of blinded eyes, broken jaws, chests blown open and fractured limbs." Certainly courage was not lacking at Dien Bien Phu.

For years, Indochina had been a geopolitical sideshow for the U.S. After World War II, Washington stood with the region's liberation movements— and so, as a gesture of friendship, a small contingent of American paratroopers was dropped into Ho Chi Minh's forward base in July 1945. Mr. Morgan gives a fascinating account of the meeting: The paratroopers are greeted by a banner hailing "our American friends," and a U.S. medic treats Ho for a dangerously high fever. Says Mr. Morgan: "It is entirely possible that the life of the future president of North Vietnam was saved by an American medic."

Irony of ironies.

Of course the early friendship frayed as anticommunism gripped 1950s Washington. No fewer than seven U.S. presidents and would-be presidents appear in Mr. Morgan's book, and their words make compelling reading, given what was to come. As Dien Bien Phu nears collapse, Eisenhower worries about falling dominoes in Southeast Asia but remains steadfast against intervening on France's behalf. "No one could be more bitterly opposed to ever getting the U.S. involved in a hot war in that region than I am." John F. Kennedy, a senator from Masschusetts at the time, is just as firm: "To pour money, matériel and men into the jungles of Indochina without at least a remote prospect of victory would be dangerously futile and self-destructive." Among future commanders in chief, only Richard Nixon stands unabashedly for intervention.

Seven.

Valley of Death

By Ted Morgan

Random House, 722 pages, $35

Still, as the French plight worsened, American diplomats searched for ways to help. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles pressed Congress and the British for a muscular response, but Dulles found few takers. "No more Koreas, with the U.S. furnishing 90% of the manpower," vowed Senate Majority Leader William Knowland, a Republican from California. As monsoons turned Dien Bien Phu to muck, diplomacy bogged down in its own way. No reinforcements would be forthcoming. In the end, the Vietminh laid siege to the French positions, swarming the valley and capturing thousands of prisoners. For France, the catastrophe meant the end of an era, the loss of a jewel in its colonial realm. For Vietnam, it meant partition into North and South. And for the U.S.—though no one knew it then—it meant the seeds had been sown for another Indochina war.

"Valley of Death" draws deeply on documentary evidence from all sides—French and Vietnamese, American and British, Russian and Chinese. Mr. Morgan's chronicle is exhaustive— sometimes overly so. There are nearly 200 pages of buildup before Dien Bien Phu is mentioned. On the diplomatic front, though one marvels at Mr. Morgan's ability to bring the reader into the negotiating rooms, after a while one finds oneself eager to leave.

Much has been made of Dien Bien Phu's lessons—lessons that the U.S. perhaps should have heeded in Vietnam: the tenacity of the country's indigenous forces, their passion and organization, and the difficulties posed by climate and terrain. But the descriptions of battle in "Valley of Death" are instructive for any military endeavor. At its best, the book is a blistering indictment of commanders whose missteps and arrogance condemn young soldiers to terrible fates. Mr. Morgan tells the haunting story of a French colonel who takes his own life after the fall of a key position. A few days later a young officer reflects: "If all those responsible for what's happening decide to kill themselves, it's going to be quite a crowd in Paris as well as Dien Bien Phu."

—Mr. Nagorski, a senior producer at ABC News, is the author of "Miracles on the Water: The Heroic Survivors of a World War II U-Boat Attack."

Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

French paratroopers landing at Dien Bien Phu in November 1953.

In November 1953, France was in its eighth year of war for control over Indochina. Things were going poorly—Vietnamese guerrillas, or Vietminh, held the upper hand—and at a strategy session in Saigon the French commander, Gen. Henri Navarre, outlined his latest plan. "I'm thinking of occupying the basin of Dien Bien Phu," he began. "The goal of this risky operation will be to defend Laos." He went on to argue that the move would draw the Vietminh into a battle they could not win. France had the advantage of air power. A base at Dien Bien Phu—in the northwest corner of Vietnam, near the Laos border—could be resupplied by air, while guerrilla leader Ho Chi Minh's cadres would be forced to move huge numbers of men and matériel through miles of mountain jungle. Finishing his presentation, Gen. Navarre turned to the group. "What do you think?"

The politicians were onboard—but the officers balked. The military men were "unanimous in objection," one senior officer noted. Building a base in a mountain valley, they told Gen. Navarre, presented formidable challenges. Dropping in paratroopers would be dangerous, resupplying the base difficult, and Dien Bien Phu would drain manpower from more important theaters—all for questionable military gain. Nevertheless, Gen. Navarre got his base. Within months—on May 7, 1954, to be exact—Dien Bien Phu was overrun by the Vietminh. Two years later Gen. Navarre was rewriting history in his memoir of the war. "No unfavorable opinion," he wrote, "was expressed before the battle."

The annals of warfare are of course studded with questionable military decisions and after-battle lies, but for sheer hubris and incompetence it is hard to match what happened before and during the 56-day battle for Dien Bien Phu. Ted Morgan's "Valley of Death" is an authoritative account of those days—but it's also a history of the early U.S. involvement in Indochina. "The words Dien Bien Phu," President Dwight Eisenhower told a conference of newspaper publishers in April 1954, "are no longer just a funny-sounding name to be dismissed from the breakfast conversation because we don't know where it is." Indeed, by then Dien Bien Phu was proving a disaster for the French—one that held warning signs for the U.S.

A lesson not heeded.

Nearly every French assumption would be punctured that spring. None proved more disastrous than Gen. Navarre's faith in the power of air supremacy. The Vietnamese, led by the brilliant general Vo Nguyen Giap (whom the Americans would face a decade later), moved a seemingly limitless supply of men and munitions through the jungle to Dien Bien Phu. It was a mind-bending feat, and it gave the Vietminh high ground above the French base. In a memorable analysis, Ho Chi Minh turned a helmet upside down, pointed to the bottom and said: "That's where the French are." Fingering the helmet's rim, he added, "that's where we are. They will never get out."

Air power was held to be a significant advantage by US politicians and generals, and the Vietminh, relabeled Viet Cong and North Vietnamese, flouted as inferior.

Ho was right—and his forces held other advantages. China sent the Vietminh food, medicine and heavy weaponry. As a guerrilla force, the Vietminh enjoyed the edge in motivation and in knowledge of terrain. As Mr. Morgan writes: "The French had an air force. The Vietminh had home-field advantage and could count on the support of the rural population."

In the meantime, French blunders multiplied. France's commissioner general for Indochina was "better known for his champagne dinners in Saigon than his military knowledge." As soldiers died waiting for fresh supplies of food and medicine, parachute teams were delayed because they lacked training certificates. All the while, horrors accumulated on the battlefield. Wounded men languished in overcrowded wards; trenches filled with corpses; monsoon rains flooded the French camp. As conditions deteriorated, evacuation became nearly impossible. Mr. Morgan draws a stirring portrait of the French medic Paul Grauwin, who worked in soaked-through, maggot-infested tents handling "an unending procession of blinded eyes, broken jaws, chests blown open and fractured limbs." Certainly courage was not lacking at Dien Bien Phu.

For years, Indochina had been a geopolitical sideshow for the U.S. After World War II, Washington stood with the region's liberation movements— and so, as a gesture of friendship, a small contingent of American paratroopers was dropped into Ho Chi Minh's forward base in July 1945. Mr. Morgan gives a fascinating account of the meeting: The paratroopers are greeted by a banner hailing "our American friends," and a U.S. medic treats Ho for a dangerously high fever. Says Mr. Morgan: "It is entirely possible that the life of the future president of North Vietnam was saved by an American medic."

Irony of ironies.

Of course the early friendship frayed as anticommunism gripped 1950s Washington. No fewer than seven U.S. presidents and would-be presidents appear in Mr. Morgan's book, and their words make compelling reading, given what was to come. As Dien Bien Phu nears collapse, Eisenhower worries about falling dominoes in Southeast Asia but remains steadfast against intervening on France's behalf. "No one could be more bitterly opposed to ever getting the U.S. involved in a hot war in that region than I am." John F. Kennedy, a senator from Masschusetts at the time, is just as firm: "To pour money, matériel and men into the jungles of Indochina without at least a remote prospect of victory would be dangerously futile and self-destructive." Among future commanders in chief, only Richard Nixon stands unabashedly for intervention.

Seven.

Valley of Death

By Ted Morgan

Random House, 722 pages, $35

Still, as the French plight worsened, American diplomats searched for ways to help. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles pressed Congress and the British for a muscular response, but Dulles found few takers. "No more Koreas, with the U.S. furnishing 90% of the manpower," vowed Senate Majority Leader William Knowland, a Republican from California. As monsoons turned Dien Bien Phu to muck, diplomacy bogged down in its own way. No reinforcements would be forthcoming. In the end, the Vietminh laid siege to the French positions, swarming the valley and capturing thousands of prisoners. For France, the catastrophe meant the end of an era, the loss of a jewel in its colonial realm. For Vietnam, it meant partition into North and South. And for the U.S.—though no one knew it then—it meant the seeds had been sown for another Indochina war.

"Valley of Death" draws deeply on documentary evidence from all sides—French and Vietnamese, American and British, Russian and Chinese. Mr. Morgan's chronicle is exhaustive— sometimes overly so. There are nearly 200 pages of buildup before Dien Bien Phu is mentioned. On the diplomatic front, though one marvels at Mr. Morgan's ability to bring the reader into the negotiating rooms, after a while one finds oneself eager to leave.

Much has been made of Dien Bien Phu's lessons—lessons that the U.S. perhaps should have heeded in Vietnam: the tenacity of the country's indigenous forces, their passion and organization, and the difficulties posed by climate and terrain. But the descriptions of battle in "Valley of Death" are instructive for any military endeavor. At its best, the book is a blistering indictment of commanders whose missteps and arrogance condemn young soldiers to terrible fates. Mr. Morgan tells the haunting story of a French colonel who takes his own life after the fall of a key position. A few days later a young officer reflects: "If all those responsible for what's happening decide to kill themselves, it's going to be quite a crowd in Paris as well as Dien Bien Phu."

—Mr. Nagorski, a senior producer at ABC News, is the author of "Miracles on the Water: The Heroic Survivors of a World War II U-Boat Attack."

Tuesday, February 2, 2010

Thursday, January 14, 2010

Feature films as history

Selected papers from a conference sponsored by Zentrum für Interdisziplinäre Forschung, University of Bielefeld held in 1979.

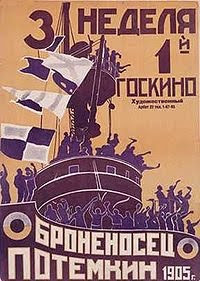

Cover of book shows "Jacket illustration of Battleship Potemkin poster from the National Film Archive, London" of a sailor with the ship's name on the headband of his cap.

The book contains papers on:

1. Introduction: Feature films as history

2. Battleship Potemkin

3. Germany and France in 1920s

4. Jean Renoir

5. British films, 1935-1947

6. Film censorship in Liberal England

7. Casablanca, Tennessee Johnson and The Negro Soldier

8. Hollywood fights anti-Semitism

Cover of book shows "Jacket illustration of Battleship Potemkin poster from the National Film Archive, London" of a sailor with the ship's name on the headband of his cap.

The book contains papers on:

1. Introduction: Feature films as history

2. Battleship Potemkin

3. Germany and France in 1920s

4. Jean Renoir

5. British films, 1935-1947

6. Film censorship in Liberal England

7. Casablanca, Tennessee Johnson and The Negro Soldier

8. Hollywood fights anti-Semitism

Saturday, October 3, 2009

American on purpose

Ferguson, Craig. (2009). American on purpose: the improbable adventures of an unlikely patriot. New York: Harper.

Ferguson, Craig. (2009). American on purpose: the improbable adventures of an unlikely patriot. New York: Harper.Craig Ferguson isn’t kidding. That’s what struck me as I turned the pages of the Scottish late-night comedian’s memoir, “American on Purpose: The Improbable Adventures of an Unlikely Patriot.” Almost every time Ferguson has a chance to go for a cheap, easy laugh — the mother’s milk of late-night comedy — he runs in the opposite direction. Take the opening scene in which he meets George W. Bush at a reception before the 2008 White House Correspondents’ Association dinner, where Ferguson, a newly minted American citizen, is to be the entertainment. He recognizes that making fun of Bush near the end of his catastrophic presidency would be like shooting fish in a barrel, so what does he do instead? He bonds with Bush as a fellow recovering alcoholic, clinking glasses of sparkling water with him as the president makes an earnest toast to America. I repeat: this is the opening scene of a book by a comedian. That’s what we in the comedy business call courage, and it pretty much sets the tone for the rest of this memoir, in which Ferguson admirably avoids wisecracks and instead goes for something like wisdom.

Craig Ferguson at the White House Correspondents’ Association dinner in 2008.

Labels:

Book review,

Citizenship,

Comedy,

Scotland,

US

Saturday, August 8, 2009

Vantage point

Vantage point

Vantage pointInteresting idea. US television (GNN, a fictional network) is carrying the US president (played aloofly by William Hurt, who sort of looks presidential) appearance in a plaza in Salamanca, Spain, at a summit of Western and Arab nations. As he is introduced and starts to speak, he is shot, twice. He is rushed off in an ambulance. Moments later a bomb explodes. A few more moments later a Secret Service agents bursts into the television truck and demands to see its tapes, and spots suspicious activity.

The film backs up to seconds before 12, and tells the same story from a different person's perspective 7 other times.

At first, the movie is gripping, the story well told. An interesting idea: how do different people see the same sequence of events? However, by the fourth or fifth, the cumulative effect becomes tiresome rather than illuminating.

After the teevee's perspective come others: Dennis Quaid's Secret Service agent, Thomas Barnes, just-returned to the job after a medical leave (having taken two bullets in protection of the president some unspecified time back); Forest Whitaker's tourist with a hand-held camera, who catches action and befriends a little girl who bumps into him and loses her ice cream; the President, who actually than actually having been shot is ensconced in a hotel room, his double having taken the bullets; one of the terrorists; and so on.

A big car chase scene follows Barnes spotting one of his fellow agents in a Spanish police uniform (he calls Washington on his cellphone, and describes the "rogue agent"). Meantime, one of the bad guys has infiltrated the hotel where the President is staying, and works his way up to POTUS's floor. A co-conspirator detonates a vest-bomb to create a diversion, and that first bad guy guns down all remaining agents, both outside and inside POTUS's room. POTUS is kidnapped, there is much shooting, more car chasing, and in the end the good guys win.

As far-fetched as it might seem, events of the last eight years have shown that wild schemes are planned, and can be executed. Technology is featured in a way that is intriguing: cellphones to call around the world; smart phones used to remotely shoot the president and detonate bombs. Alas, technology could not rescue this film. The Times review didn't mince words.

Labels:

Politics,

Spain,

Technology,

Terrorism,

US

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)