Read a story, FAA to allow tablets and e-readers during all phases of flight, (at bottom, story has: First published October 31st 2013, 10:06 am). Near the bottom is this paragraph:

Not to mention that passengers will sometimes sneak in a few Words with Friends turns when they think they can get away with it. “You can’t be looking at everybody all the time,” said Tiffany Hawk, a former flight attendant and the author of “Love Me Anyway,” a novel about airline culture. “People are always pretending to turn things off even when they’re not.”

I looked at Kirkus review of that book, which has this: ""Readers will find the book's two heroines well worth knowing."

And they are. I read 185 pages in 2 days. Story is solid, well paced, and has substance.

Publisher's Weekly: Though Hawk provides a fascinating snapshot of an industry seldom explored in fiction, the cycling between first person (Emily) and third person (KC) is distracting, and Hawk's prose turns didactic as the pace slackens.

I did not find the alternative narrators distracting, but I do agree that as the book reaches its last quarter the narrative style weakens.

Fun, worthwhile, nicely done.

Showing posts with label England. Show all posts

Showing posts with label England. Show all posts

Saturday, April 12, 2014

Love me anyway

Labels:

Absent fathers,

Airplane,

England,

Families,

Hawaii,

India,

Las Vegas,

Love,

San Francisco,

Women

Saturday, September 7, 2013

The best exotic Marigold Hotel (2011)

an ensemble cast consisting of Judi Dench, Celia Imrie, Bill Nighy, Ronald Pickup, Maggie Smith, Tom Wilkinson and Penelope Wilton, as a group of British pensioners moving to a retirement hotel in India, run by the young and eager Sonny, played by Dev Patel.

Gets 78% & 79% in Rotten Tomatoes. About right. Wilkinson charcater is very well portrayed. Patel's seems a stereotype that nearly drowns in syrup. Ebert liked it. As did Stephen Holden in the Times: The screenplay does a reasonably skillful job of interweaving its subplots and of creating some mild surprises. This is a programmatically feel-good movie whose tempered optimism and insistence that it’s never too late to leave your comfort zone and explore new horizons stays mostly (but not always) on the safe side of sentimentality. Besides its sterling cast, its ace in the hole is its pungent depiction of Jaipur’s teeming streets, which give an otherwise well-mannered movie a blinding splash of color.

Gets 78% & 79% in Rotten Tomatoes. About right. Wilkinson charcater is very well portrayed. Patel's seems a stereotype that nearly drowns in syrup. Ebert liked it. As did Stephen Holden in the Times: The screenplay does a reasonably skillful job of interweaving its subplots and of creating some mild surprises. This is a programmatically feel-good movie whose tempered optimism and insistence that it’s never too late to leave your comfort zone and explore new horizons stays mostly (but not always) on the safe side of sentimentality. Besides its sterling cast, its ace in the hole is its pungent depiction of Jaipur’s teeming streets, which give an otherwise well-mannered movie a blinding splash of color.

Saturday, September 8, 2012

Salmon Fishing in the Yemen (2012)

Better than expected, really. Fairly good, rather enjoyable.

Quirky and a little reserved, Salmon Fishing in the Yemen is nonetheless a charming little romantic drama sold by some strong central performances.

McGregor's accent is rather quirky. Scott Thomas's character was quite the caricature, and weakened the film, if anything.

Quirky and a little reserved, Salmon Fishing in the Yemen is nonetheless a charming little romantic drama sold by some strong central performances.

McGregor's accent is rather quirky. Scott Thomas's character was quite the caricature, and weakened the film, if anything.

Tuesday, March 13, 2012

South from Granada

From Spanish director Fernando Colomo comes this adaptation of Gerald Brenan's comedic autobiographical book Al sur de Granada. Matthew Goode stars as Brenan, a young Englishman of affluent and noble stock. Motivated by idealism and with a desire to become a great writer, Gerald moves to a small Spanish town to get away from the trappings of his upbringing. There, he befriends Paco, a local man played by Guillermo Toledo, who helps introduce Gerald to the town. Eventually, the beautiful Juliana (Verónica Sánchez) catches Gerald's eye, and he immediately falls for her. From there, it's up to Paco to familiarize Gerald with the local customs so that he can win the heart of Juliana. Consuelo Trujillo and Ángela Molina also star.

Fairly good film. Enjoyable enough.

Brenan is friends with Lytton Strachey and others from the Bloomsbury group, including Dora Carrington, with whom he is portrayed as being in love. In Yegen,a village in the Spanish countryside below Granada, he settles down to clear his head so he can write. However, events and people conspire to otherwise occupy him. In the drama which includes inter-class sex and a Catholic priest who can not help but be in love with a local woman, Brenan falls in love with Julianna, a local woman whom some suspect of being a witch. She is young, and falls in love, eventually, with Brenan. She also tells him she wnats to bear his baby, and is not interested in marriage.

Fairly good film. Enjoyable enough.

Brenan is friends with Lytton Strachey and others from the Bloomsbury group, including Dora Carrington, with whom he is portrayed as being in love. In Yegen,a village in the Spanish countryside below Granada, he settles down to clear his head so he can write. However, events and people conspire to otherwise occupy him. In the drama which includes inter-class sex and a Catholic priest who can not help but be in love with a local woman, Brenan falls in love with Julianna, a local woman whom some suspect of being a witch. She is young, and falls in love, eventually, with Brenan. She also tells him she wnats to bear his baby, and is not interested in marriage.

Sunday, March 11, 2012

Hereafter

46% of Rotten Tomatoes critics liked it, 40% of the audience. I agree: the film is disjointed, lathargic, and the point it makes is strained and unconvincing. The South Pacific tsunami and the London bombings are connected via the vehicle of an American (Matt Damon) who is reluctant to again use his gift (or, as he sees it, curse) of being able to connect with the departed. Why the two Europeans are teamed up with the Yank is a mystery. The French mumble, and shots of the Eiffel Tower and of extra-marital sex are used as symbols that are so clichéd as to make me wonder who the hell had the idea of including them.

RT: Despite a thought-provoking premise and Clint Eastwood's typical flair as director, Hereafter fails to generate much compelling drama, straddling the line between poignant sentimentality and hokey tedium. There are touches of flair: Damon's character loves Dickens, not Shakespeare, and when he escapes northern California and he goes to London, he winds up taking a tour of Dickens's home and attending a Dickensian lecture by Derek Jacobi. He winds up romantically linked with the French woman, but that linkup is strained; the film wanted to make that connection, and it just does, unconvincingly.

RT: Despite a thought-provoking premise and Clint Eastwood's typical flair as director, Hereafter fails to generate much compelling drama, straddling the line between poignant sentimentality and hokey tedium. There are touches of flair: Damon's character loves Dickens, not Shakespeare, and when he escapes northern California and he goes to London, he winds up taking a tour of Dickens's home and attending a Dickensian lecture by Derek Jacobi. He winds up romantically linked with the French woman, but that linkup is strained; the film wanted to make that connection, and it just does, unconvincingly.

Labels:

England,

France,

Psychic power,

San Francisco,

South Pacific,

Tsunami

Sunday, February 12, 2012

Tuesday, April 26, 2011

Brick Lane

A young Blangadeshi is sent to England to marry a man older than her, and leaves behind her sister, an irascible father, and memories of her mother drowning herself, and of happy times playing with her sister.

In London she lives with her two daughters and distant husband in an immense block apartment building that houses immigrants and others on the margins of society. After her husband quits his job in a fit of pique motivated by a perceived insult to his character and intelligence, she buys a sewing machine and begins making garments and money.

She lives for the letters her sister writes of her romantic adventures. As she reads such letters, Nazneen is transported back to her youth and her home.

Karim delivers her the raw materials and picks up her finished work is also Bangladeshi. Slowly a friendship develops between them. Her husband's indifference (his only tenderness, if it can be called that, is to take her hand in bed, before climbing on her and discharging his desire) pushes her away, and Karim's tenderness slowly seduces her.

When 9/11 happens the slow radicalization of Asian youth is propelled by the racist backlash of whites screaming invective and threatening violence ("go home, Paki" they scream, but never think that perhaps the colonialism of the homeland is, at least, partly responsible for the immigration of those they loathe).

Subtlety in storytelling renders this film weak; it could use a shot of adrenaline. Yet it is a beautiful film that tells an important and compelling story.

In London she lives with her two daughters and distant husband in an immense block apartment building that houses immigrants and others on the margins of society. After her husband quits his job in a fit of pique motivated by a perceived insult to his character and intelligence, she buys a sewing machine and begins making garments and money.

She lives for the letters her sister writes of her romantic adventures. As she reads such letters, Nazneen is transported back to her youth and her home.

Karim delivers her the raw materials and picks up her finished work is also Bangladeshi. Slowly a friendship develops between them. Her husband's indifference (his only tenderness, if it can be called that, is to take her hand in bed, before climbing on her and discharging his desire) pushes her away, and Karim's tenderness slowly seduces her.

When 9/11 happens the slow radicalization of Asian youth is propelled by the racist backlash of whites screaming invective and threatening violence ("go home, Paki" they scream, but never think that perhaps the colonialism of the homeland is, at least, partly responsible for the immigration of those they loathe).

Subtlety in storytelling renders this film weak; it could use a shot of adrenaline. Yet it is a beautiful film that tells an important and compelling story.

Labels:

Bangladesh,

England,

Immigrants,

Marriage

Sunday, March 13, 2011

Wednesday, August 11, 2010

Saturday, June 12, 2010

Yalta: the price of peace. (2010). Plokhy, Serhii

New York: Viking .

Various links include an event at the Woodrow Wilson Center, a segment on BookTV,

New York: Viking .

Various links include an event at the Woodrow Wilson Center, a segment on BookTV,

Wednesday, May 12, 2010

Operation Mincemeat

Courtesy of Jeremy Montagu/From “Operation Mincemeat” - Charles Cholmondeley, left, and Ewen Montagu in April 1943, about to put their ruse in motion.

Excellent westerns have been composed by people who could barely ride a horse, and the best writers of sex scenes are often novelists you wouldn’t wish to see naked. But when it comes to spy fiction, life and art tend to collide fully: nearly all of the genre’s greatest practitioners worked in intelligence before signing their first book contract. “W. Somerset Maugham, John Buchan, Ian Fleming, Graham Greene, John le Carré: all had experienced the world of espionage firsthand,” Ben Macintyre writes in his new book, “Operation Mincemeat.” “For the task of the spy is not so very different from that of the novelist: to create an imaginary, credible world and then lure others into it by words and artifice.” Both are lurkers, confounders, ironists, betrayers: in a word, they’re spooks.

Mr. Macintyre himself writes about spies so craftily, and so ebulliently, that you half suspect him of being some type of spook himself. It is apparently not so. He is a benign-seeming writer at large and associate editor at The Times of London, a father of three and the author of five previous, respected nonfiction books, including “Agent Zigzag: A True Story of Nazi Espionage, Love, and Betrayal” (2007). Perhaps he is also controlling predator drones and a flock of assassins from a basement compound. But, alas, I doubt it.

“Operation Mincemeat” is utterly, to employ a dead word, thrilling. But to call it thus is to miss the point slightly, in terms of admiring it properly. Mr. Macintyre has got his hands around a true story that’s so wind-swept, so weighty and so implausible that the staff of a college newspaper, high on glue sticks, could surely take its basic ingredients and not completely muck things up.

I first read about this in David Ignatius's book, Body of Lies. That was after seeing the film with Leo DiCaprio. In turn, I went to the film, The man who never was, with Clifton Webb, and its eponymous book.

Excellent westerns have been composed by people who could barely ride a horse, and the best writers of sex scenes are often novelists you wouldn’t wish to see naked. But when it comes to spy fiction, life and art tend to collide fully: nearly all of the genre’s greatest practitioners worked in intelligence before signing their first book contract. “W. Somerset Maugham, John Buchan, Ian Fleming, Graham Greene, John le Carré: all had experienced the world of espionage firsthand,” Ben Macintyre writes in his new book, “Operation Mincemeat.” “For the task of the spy is not so very different from that of the novelist: to create an imaginary, credible world and then lure others into it by words and artifice.” Both are lurkers, confounders, ironists, betrayers: in a word, they’re spooks.

Mr. Macintyre himself writes about spies so craftily, and so ebulliently, that you half suspect him of being some type of spook himself. It is apparently not so. He is a benign-seeming writer at large and associate editor at The Times of London, a father of three and the author of five previous, respected nonfiction books, including “Agent Zigzag: A True Story of Nazi Espionage, Love, and Betrayal” (2007). Perhaps he is also controlling predator drones and a flock of assassins from a basement compound. But, alas, I doubt it.

“Operation Mincemeat” is utterly, to employ a dead word, thrilling. But to call it thus is to miss the point slightly, in terms of admiring it properly. Mr. Macintyre has got his hands around a true story that’s so wind-swept, so weighty and so implausible that the staff of a college newspaper, high on glue sticks, could surely take its basic ingredients and not completely muck things up.

I first read about this in David Ignatius's book, Body of Lies. That was after seeing the film with Leo DiCaprio. In turn, I went to the film, The man who never was, with Clifton Webb, and its eponymous book.

Labels:

Book review,

England,

Spying,

WW2

Thursday, April 29, 2010

Fortune's Ambassador

Moses Montefiore

By Abigail Green

Belknap/Harvard, 540 pages, $35

Moses Montefiore, a world-renowned figure in the 19th century, was virtually forgotten by the 20th and is remembered today, at times, simply by the resonance of his name. A hospital in the Bronx is named for him, another in Pittsburgh, and a Jewish quarter in Jerusalem just outside the Old City. The accomplishments of some of Montefiore's descendants—including a pugnacious Anglican bishop—may remind us the progenitor's renown, but his story certainly needs to be retold. It is a remarkable one.

Not a perfect being, perhaps a philanderer, he was materially successful, married into the Rothschild family, knighted at 51, he lived to be 101.

It is a little hard for us to imagine Montefiore's public role, since there is no equivalent today. He was roving foreign minister and emissary of a people without a state. In many places they called him "sar"—a Hebrew word for minister, a person of great influence. People attributed to him almost magical powers.

But he wasn't a magician. He did, though, accomplish many things.

That Montefiore had been received for an audience by Czar Nicholas I, not known as a philo-Semite, did matter. The czar had given orders, on the occasion of Montefiore's visit to the Russian capital, that the guard in front of his palace be constituted of Jewish soldiers, whom he praised as being as brave as the ancient Maccabeans.

Nicholas I: (Russian: Николай I Павлович, Nikolaj I Pavlovič), (6 July [O.S. 25 June] 1796 – 2 March [O.S. 18 February] 1855), was the Emperor of Russia from 1825 until 1855, known as one of the most reactionary of the Russian monarchs. On the eve of his death, the Russian Empire reached its historical zenith spanning over 20 million square kilometers. In his capacity as the emperor he was also the King of Poland and the Grand Duke of Finland.

Ms. Green writes deftly and tells Montefiore's story with a admirable thoroughness. (She is herself a professional historian.) "Moses Montefiore" is mercifully free of academic theory. It is exactly what a good biography should be—fair and illuminating without ever descending to hagiography. Still, it is clear that Montefiore was a genuinely good man. Their number in history is not substantial, and praise should be given where it is due.

A fascinating story; sounds to be a good read. The reviewer, Walter Laqueur is the author, most recently of "Best of Times, Worst of Times: Memoirs of a Political Education" (University of New England Press, 2010).

By Abigail Green

Belknap/Harvard, 540 pages, $35

Moses Montefiore, a world-renowned figure in the 19th century, was virtually forgotten by the 20th and is remembered today, at times, simply by the resonance of his name. A hospital in the Bronx is named for him, another in Pittsburgh, and a Jewish quarter in Jerusalem just outside the Old City. The accomplishments of some of Montefiore's descendants—including a pugnacious Anglican bishop—may remind us the progenitor's renown, but his story certainly needs to be retold. It is a remarkable one.

Not a perfect being, perhaps a philanderer, he was materially successful, married into the Rothschild family, knighted at 51, he lived to be 101.

It is a little hard for us to imagine Montefiore's public role, since there is no equivalent today. He was roving foreign minister and emissary of a people without a state. In many places they called him "sar"—a Hebrew word for minister, a person of great influence. People attributed to him almost magical powers.

But he wasn't a magician. He did, though, accomplish many things.

That Montefiore had been received for an audience by Czar Nicholas I, not known as a philo-Semite, did matter. The czar had given orders, on the occasion of Montefiore's visit to the Russian capital, that the guard in front of his palace be constituted of Jewish soldiers, whom he praised as being as brave as the ancient Maccabeans.

Nicholas I: (Russian: Николай I Павлович, Nikolaj I Pavlovič), (6 July [O.S. 25 June] 1796 – 2 March [O.S. 18 February] 1855), was the Emperor of Russia from 1825 until 1855, known as one of the most reactionary of the Russian monarchs. On the eve of his death, the Russian Empire reached its historical zenith spanning over 20 million square kilometers. In his capacity as the emperor he was also the King of Poland and the Grand Duke of Finland.

Ms. Green writes deftly and tells Montefiore's story with a admirable thoroughness. (She is herself a professional historian.) "Moses Montefiore" is mercifully free of academic theory. It is exactly what a good biography should be—fair and illuminating without ever descending to hagiography. Still, it is clear that Montefiore was a genuinely good man. Their number in history is not substantial, and praise should be given where it is due.

A fascinating story; sounds to be a good read. The reviewer, Walter Laqueur is the author, most recently of "Best of Times, Worst of Times: Memoirs of a Political Education" (University of New England Press, 2010).

Sunday, March 21, 2010

Appetite for America

Denver Public Library - The Fred Harvey restaurant at Dearborn Station in Chicago opened in 1899.

In 1946, when Judy Garland starred in a movie called "The Harvey Girls," no one had to explain the title to the film-going public. The Harvey Girls were the young women who waited tables at the Fred Harvey restaurant chain, and they were as familiar in their day as Starbucks baristas are today. In many of the dusty railroad towns out West in the late 1880s and early decades of the 1900s, there was only one place to get a decent meal, one place to take the family for a celebration, one place to eat when the train stopped to load and unload: a Fred Harvey restaurant. And the owner's decision to import an all-female waitstaff meant that his restaurants offered up one more important and hard-to-find commodity in cowboy country: wives.

It was a brilliant formula, and for a long time Fred Harvey's name was synonymous in America with good food, efficient service and young women. Today, though, you'd be hard-pressed to find anyone aware of the prominent role Harvey played in civilizing the West and raising America's dining standards. His is one of those household names now stashed somewhere up in the attic.

Helen Harvey Mills

Fred Harvey in the early 1880s.

In "Appetite for America," Stephen Fried aims to give Fred Harvey his due, making an impressive case for this Horatio Alger tale written in mashed potatoes and gravy. Fred Harvey restaurants grew up with the railroads in the American West beginning in the 1870s, with opulent dining rooms in major train stations and relatively luxurious eating spots at more remote railroad outposts. Eventually, the Fred Harvey brand spread to 65 restaurants and lunch counters, 60 dining cars and a dozen large Harvey-owned hotels. And Harvey understood that the reputation of his brand depended on his own personal standards for excellence—which is why he called his company simply "Fred Harvey," not Fred Harvey Co. or Harvey Inc.

He built "the first national chain of anything," writes Mr. Fried. He tells his story in crisp prose and delightful detail, from staggering statistics—in 1905, when moving fresh food across the country was still a challenge, Harvey restaurants served up 6.48 million eggs and two million pounds of beef—to savory recipes, including those for "Plantation Beef Stew on Hot Buttermilk Biscuits" and "Finnan Haddie Dearborn" (smoked haddock). Mr. Fried also deftly captures the significance of how Harvey remade the American rail experience: For the first time in the U.S., a traveler could step off his train and know exactly what to expect: hot coffee, good food and friendly service—all of it delivered in time to get him back on the train before it pulled out of the station.

When Harvey left his home in England at age 15 in 1850, he later recalled, he had two pounds in his pocket and no particular plan of action. He soon found work as a "pot walloper," or dishwasher, at a restaurant on the Hudson River piers in New York. And like so many pot wallopers, then and now, he worked his way up: busboy, waiter, line cook. Eventually, in another classic move, Harvey headed west. In Kansas he worked two jobs, as a railroad ticket agent and as a newspaper ad salesman. With the completion of the first transcontinental railroad in 1869 and the arrival of a postwar business boom, rail commerce thrived—as did Fred Harvey. He became a freight agent, traveling the countryside and arranging with farmers, manufacturers and miners to ship their goods.

Appetite for America

By Stephen Fried

Bantam, 518 pages, $27

Book excerpt.

Enduring the endless smoke, soot, stale air and unappetizing food that typified train journeys of the era, Harvey decided that he at least could do something about the food. In the 1870s George Pullman was building elegant sleeping cars and handsomely appointed dining cars, but the dining cars were unsuccessful: On trains of that time passengers couldn't walk between cars, so hungry travelers were unable to reach the dining car except when the train stopped—and diners long finished with their meals had to wait to go back to their seats. Passengers unable to afford the expensive fare were at the mercy, as Mr. Fried writes, "of stomach-turning depot meals." Harvey believed there was money to be made: "Fred was certain it was possible to serve the finest cuisine imaginable along the train tracks in the middle of nowhere."

It was this ambition—to serve not just fast food but the best possible fast food—that would mark his true contribution to American business. Before there were four-star hotels or restaurants, he set out to create a brand that delivered the goods quickly without cutting corners on quality. He ran his railroad-restaurant business, operating along the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe lines, like a military operation. His waitresses lived in company housing and kept curfew. On and off the job, they were expected to follow rules: "Have a Sincere Interest in People" was the first on a list that Mr. Fried reprints. Another reminded employees that "Tact is an Asset and HONESTY is still a Virtue." Harvey's decrees didn't necessarily apply to Harvey: A newspaper in 1881 reported that when he fired the manager of a train-station restaurant in Deming, N.M., Harvey threw the man out the front door onto the train platform "and the dining room equipment followed after him in quick order."

As his empire expanded, Harvey built the first national chain of hotels and the first chain of bookstores. He also helped establish the Grand Canyon as a major tourist destination and sparked some of the country's early appreciation and preservation of Native American culture.

The tale of Harvey's rise, as told by Mr. Fried, is a business story and a sweeping social history populated with memorable characters. We meet, for instance, David Benjamin, who was a 22-year-old bank teller in Leavenworth, Kan., Harvey's base of operations, when the businessman offered him a job in 1881. Soon the matter-of-fact Benjamin was the mercurial Harvey's right-hand man, "creating elaborate systems to put Fred Harvey's demands and dreams into memo and manual form, making 'the standard' easier to understand."

University of Arizona Library - A 'Harvey Girl' in Emporia, Kan., where the restaurant opened in 1888. Fred Harvey also owned a farm in Emporia.

When Harvey dies in 1901, we watch his son, Ford Harvey, execute such a smooth transition and maintain such a low profile that hardly anyone knows the company's namesake is gone. Ford Harvey has all of the old man's obsessive attention to detail. When he receives a letter from a patron claiming that another establishment serves better olives than Fred Harvey's, Ford is taken aback and writes to the rival, asking for a bottle of the olives. When the bottle arrives, he announces to his top staff the good news: The olives are the same as the ones served in the Harvey chain—the letter-writer "just thought those olives tasted better."

The Fred Harvey company lasted the better part of a century and through three generations of family management, but as automobile travel rose in popularity in the 1930s and 1940s, the age of the passenger train began to wane, taking with it the Harvey empire.

When Judy Garland played an onscreen Harvey Girl in 1946, the movie was a great success, and one of its songs, "On the Atchison, Topeka and the Santa Fe," became a No. 1 hit. There were hopes that the movie might somehow spark a revival in the Fred Harvey fortunes, but by then another hospitality genius was on the scene, and Howard Johnson had set up shop beside the nation's highways.

By Jonathan Eig

—Mr. Eig's "Get Capone: The Secret Plot That Captured America's Most Wanted Gangster," will be published next month by Simon & Schuster.

In 1946, when Judy Garland starred in a movie called "The Harvey Girls," no one had to explain the title to the film-going public. The Harvey Girls were the young women who waited tables at the Fred Harvey restaurant chain, and they were as familiar in their day as Starbucks baristas are today. In many of the dusty railroad towns out West in the late 1880s and early decades of the 1900s, there was only one place to get a decent meal, one place to take the family for a celebration, one place to eat when the train stopped to load and unload: a Fred Harvey restaurant. And the owner's decision to import an all-female waitstaff meant that his restaurants offered up one more important and hard-to-find commodity in cowboy country: wives.

It was a brilliant formula, and for a long time Fred Harvey's name was synonymous in America with good food, efficient service and young women. Today, though, you'd be hard-pressed to find anyone aware of the prominent role Harvey played in civilizing the West and raising America's dining standards. His is one of those household names now stashed somewhere up in the attic.

Helen Harvey Mills

Fred Harvey in the early 1880s.

In "Appetite for America," Stephen Fried aims to give Fred Harvey his due, making an impressive case for this Horatio Alger tale written in mashed potatoes and gravy. Fred Harvey restaurants grew up with the railroads in the American West beginning in the 1870s, with opulent dining rooms in major train stations and relatively luxurious eating spots at more remote railroad outposts. Eventually, the Fred Harvey brand spread to 65 restaurants and lunch counters, 60 dining cars and a dozen large Harvey-owned hotels. And Harvey understood that the reputation of his brand depended on his own personal standards for excellence—which is why he called his company simply "Fred Harvey," not Fred Harvey Co. or Harvey Inc.

He built "the first national chain of anything," writes Mr. Fried. He tells his story in crisp prose and delightful detail, from staggering statistics—in 1905, when moving fresh food across the country was still a challenge, Harvey restaurants served up 6.48 million eggs and two million pounds of beef—to savory recipes, including those for "Plantation Beef Stew on Hot Buttermilk Biscuits" and "Finnan Haddie Dearborn" (smoked haddock). Mr. Fried also deftly captures the significance of how Harvey remade the American rail experience: For the first time in the U.S., a traveler could step off his train and know exactly what to expect: hot coffee, good food and friendly service—all of it delivered in time to get him back on the train before it pulled out of the station.

When Harvey left his home in England at age 15 in 1850, he later recalled, he had two pounds in his pocket and no particular plan of action. He soon found work as a "pot walloper," or dishwasher, at a restaurant on the Hudson River piers in New York. And like so many pot wallopers, then and now, he worked his way up: busboy, waiter, line cook. Eventually, in another classic move, Harvey headed west. In Kansas he worked two jobs, as a railroad ticket agent and as a newspaper ad salesman. With the completion of the first transcontinental railroad in 1869 and the arrival of a postwar business boom, rail commerce thrived—as did Fred Harvey. He became a freight agent, traveling the countryside and arranging with farmers, manufacturers and miners to ship their goods.

Appetite for America

By Stephen Fried

Bantam, 518 pages, $27

Book excerpt.

Enduring the endless smoke, soot, stale air and unappetizing food that typified train journeys of the era, Harvey decided that he at least could do something about the food. In the 1870s George Pullman was building elegant sleeping cars and handsomely appointed dining cars, but the dining cars were unsuccessful: On trains of that time passengers couldn't walk between cars, so hungry travelers were unable to reach the dining car except when the train stopped—and diners long finished with their meals had to wait to go back to their seats. Passengers unable to afford the expensive fare were at the mercy, as Mr. Fried writes, "of stomach-turning depot meals." Harvey believed there was money to be made: "Fred was certain it was possible to serve the finest cuisine imaginable along the train tracks in the middle of nowhere."

It was this ambition—to serve not just fast food but the best possible fast food—that would mark his true contribution to American business. Before there were four-star hotels or restaurants, he set out to create a brand that delivered the goods quickly without cutting corners on quality. He ran his railroad-restaurant business, operating along the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe lines, like a military operation. His waitresses lived in company housing and kept curfew. On and off the job, they were expected to follow rules: "Have a Sincere Interest in People" was the first on a list that Mr. Fried reprints. Another reminded employees that "Tact is an Asset and HONESTY is still a Virtue." Harvey's decrees didn't necessarily apply to Harvey: A newspaper in 1881 reported that when he fired the manager of a train-station restaurant in Deming, N.M., Harvey threw the man out the front door onto the train platform "and the dining room equipment followed after him in quick order."

As his empire expanded, Harvey built the first national chain of hotels and the first chain of bookstores. He also helped establish the Grand Canyon as a major tourist destination and sparked some of the country's early appreciation and preservation of Native American culture.

The tale of Harvey's rise, as told by Mr. Fried, is a business story and a sweeping social history populated with memorable characters. We meet, for instance, David Benjamin, who was a 22-year-old bank teller in Leavenworth, Kan., Harvey's base of operations, when the businessman offered him a job in 1881. Soon the matter-of-fact Benjamin was the mercurial Harvey's right-hand man, "creating elaborate systems to put Fred Harvey's demands and dreams into memo and manual form, making 'the standard' easier to understand."

University of Arizona Library - A 'Harvey Girl' in Emporia, Kan., where the restaurant opened in 1888. Fred Harvey also owned a farm in Emporia.

When Harvey dies in 1901, we watch his son, Ford Harvey, execute such a smooth transition and maintain such a low profile that hardly anyone knows the company's namesake is gone. Ford Harvey has all of the old man's obsessive attention to detail. When he receives a letter from a patron claiming that another establishment serves better olives than Fred Harvey's, Ford is taken aback and writes to the rival, asking for a bottle of the olives. When the bottle arrives, he announces to his top staff the good news: The olives are the same as the ones served in the Harvey chain—the letter-writer "just thought those olives tasted better."

The Fred Harvey company lasted the better part of a century and through three generations of family management, but as automobile travel rose in popularity in the 1930s and 1940s, the age of the passenger train began to wane, taking with it the Harvey empire.

When Judy Garland played an onscreen Harvey Girl in 1946, the movie was a great success, and one of its songs, "On the Atchison, Topeka and the Santa Fe," became a No. 1 hit. There were hopes that the movie might somehow spark a revival in the Fred Harvey fortunes, but by then another hospitality genius was on the scene, and Howard Johnson had set up shop beside the nation's highways.

By Jonathan Eig

—Mr. Eig's "Get Capone: The Secret Plot That Captured America's Most Wanted Gangster," will be published next month by Simon & Schuster.

Labels:

Commerce,

England,

Progress,

Railroad,

US History

Thursday, March 18, 2010

A week in December

Faulks's hugely ambitious novel is a delightful and witty satire on contemporary London life, says Justin Cartwright

Faulks's new novel is a study of contemporary London. Photograph: Sophia Evans

Sebastian Faulks's new novel, set in one week in December 2007, is very ambitious. It aspires to be a state-of-the-nation book, a satirical comedy of metropolitan literary life, a sweeping, Dickensian look at contemporary London, a serious examination of Islam and the reasons for radicalism among young Muslims, a thriller, a satire on the Notting Hill Cameroonians and a detailed look at the sharp financial practices that led to the collapse. There's London football, reality TV, cyber porn, a love story or two. As if all that weren't enough, it is a roman a clef, which has already provided fun for metropolitan journalists as they speculate about the identity of the various characters.

A Week in December. Sebastian Faulks

pp400,Hutchinson,£18.99

The scene is set with the wife of a Tory MP organising a dinner party for the benefit of her husband's career in somewhere evoking Notting Hill. Every guest is chosen to suggest that the MP is a Renaissance man. We are reminded of Alan Hollinghurst's The Line of Beauty, as though all wealthy Tories inevitably have grand gatherings with deep undercurrents of class, ambition and financial chicanery. As she goes through the guest list, we immediately know that they are all going to be linked in some way. The guests are mostly wealthy men and their wives, owners of hedge funds and banks and so on.

There is also a manufacturer who has been invited to lend multicultural credibility. Farooq al-Rashid has made his money in pickles; he is a substantial contributor to the party and he has a son – the alarm bells ring stridently at this point – called Hassan who, in his parents' opinion, is rather too interested in the true message of Islam. While they simply want to enjoy the benefits of wealth and acceptance, he is planning to blow the Kafir world to pieces.

John Veals is a hedge fund owner who has made hundreds of millions by barely legal activity and he sees an opportunity to make much, much more by causing a big bank to collapse. Faulks has clearly done extensive research, sometimes not wholly digested by the plot, but admirably authentic. The real problem with Veals, though, is that he never lifts off the page. This is partly because the book is so crowded that Faulks doesn't have the space to produce a rounded character. Any novel that tries to take the temperature of the nation needs a fully human central character to pull the big themes together. Dickens's Merdle and Tom Wolfe's Sherman McCoy are horribly believable.

Anyway, besides the toffs, there are two less plutocratic guests invited to the dinner party, one an unsuccessful and bookish young barrister, Gabriel Northwood, the other a jobbing literary journalist, R Tranter. Tranter is all too clearly based on journalist DJ Taylor. Tranter admires Thackeray and writes for a satirical magazine, the Toad; Taylor has written a biography of Thackeray and writes a literary column for Private Eye. Tranter uses the Toad to work out his disdain for, and envy of, more successful writers. He also has a habit in his reviews of sadly concluding that most successful authors are ultimately deploying a few cheap tricks and are con artists, even if they are good. His reaction when he reads a novel by a rival critic – "It was worse, far worse, than he had dared to hope" – is spot on. There is a brilliant literary prize scene which was painfully familiar to me. Faulks knows the book world and satirises it with brio, but he can give up any hope of winning the Costa Prize after this.

The marriage of these elements is mostly smooth, with the best strands involving the literary world and the hypocrisies and presumption of the rich. Less successful is Faulks's rather plodding analysis of why young men turn to Islam. All too often, we are subjected to reiterations of the contradictions of the Qur'an and Islam's appeal to the disaffected, which are strangely lifeless as fiction. In John Updike's 2006 novel , the conversations between the potential bomber and his mentor also suffered from a certain stiffness. Maybe it is difficult to cross this particular cultural barrier. Another key character, Jenni Fortune (not invited to the dinner party), is a book-loving, cyber-obsessed young tube driver; her world isn't fully realised either.

But Gabriel Northwood, the barrister, is a fine character. He is slightly diffident, very human in his weaknesses, observant and well read. Remembering the great love of his life, a married woman, Northwood wonders about "this desperate passion… was it really such an enviable way to live, always at the edge of panic, desperate for a cellphone bleep, all your judgments skewed?" Some time before the book opens, he met Jenni, when he was junior to a QC on a case involving London Transport: Jenni had been driving a train when somebody jumped on to the line. He has taken to seeing her on the slightest pretext; we know that they are going to fall in love, despite their different backgrounds.

As the week progresses, we see Farooq al-Rashid preparing for his investiture with the OBE at Buckingham Palace; he is fretting over what he is going to say to the Queen. For a few months, he has been employing Tranter to coach him on the Queen's literary preferences. At their first meeting, Tranter dismissed all the books Rashid had been advised to buy ("OT – Oirish Twaddle", the "higher bogus", "poor man's Somerset Maugham" or "from the man who put the anal into banal") and recommended instead an obscure Victorian writer and Dick Francis.

In a highly nervous state, Rashid is trying to memorise the verdicts Tranter delivered in case Her Majesty should ask him what he reads. Meanwhile, young Hassan has to juggle his timetable in order to go on from Buckingham Palace to the bombing of a hospital with a large maternity unit. The scene at the investiture is hilarious, particularly as Prince Charles stands in for his mother. One of the flunkeys, as he boxes up Farooq's medal, says: "How was the Princess? She's ever such a chatterbox when she gets going. There you are, sir. One little gong."

As John Veals puts the finishing touches to his plan to bring down a bank – and incidentally destroy the livelihoods of thousands of African farmers – his teenage son, Finbar, is experimenting with skunk. This leads to a terrible psychotic episode and admission to hospital where it is touch and go if he will recover or lapse into schizophrenia. His mother, Vanessa, ultimately comes to his aid, overcome by guilt for her neglect.

Finally, the dinner party takes place. One of the guests, Roger Malpasse, delivers a fine drunken rant against the financial malpractice that is leading to crisis: "It's a fraud as old as markets themselves. The only difference is that it's been done on a titanic scale. At the invitation of the politicians. Behind the backs of the regulators and with the dumb connivance of the auditors. And with the fatal misunderstanding of the ratings agencies." This is one of the strongest moments in the novel, and unexpected, because up to now Roger has been portrayed only as a man who likes a drink, starting with a "phlegm-cracker" early in the day, moving on to a "sharpener" before food and finishing with a "zonker", which is virtually anything he can tip into a glass at the end of the day.

A Week in December is a little too long, a little too prolix. And yet it survives all this to be a compelling tale of contemporary London. I am not sure that it is the classic state-of-the-nation novel we need, but I have no doubt at all that it will outsell the higher bogus by a very long way.

Sebastian Faulks

Born 20 April 1953 and later educated at Emmanuel College, Cambridge. Now lives with his wife, Victoria, and three children in west London.

1984 His first published novel, A Trick of the Light

1986 Appointed the first literary editor of the Independent, then deputy editor of the Independent on Sunday

1989 The Girl at the Lion d'Or, the first of his French Trilogy, is published.

1993 Birdsong published.

1998 Charlotte Gray wins the James Tait Black Memorial Prize and is made into a film starring Cate Blanchett.

2006 Publishes the non-fiction Pistache, a series of parodies of other writers.

2008 Writes Devil May Care, a new James Bond novel to mark the centenary of Ian Fleming's birth.

2002 Made a CBE and in 2007 an honorary fellow of Emmanuel College.

He says: "I found it extremely difficult to get going as a novelist."

They say: "A masterpiece, one of the great novels of this or any other century." Trevor Nunn on Human Traces (2005). Oliver Marre

Faulks's new novel is a study of contemporary London. Photograph: Sophia Evans

Sebastian Faulks's new novel, set in one week in December 2007, is very ambitious. It aspires to be a state-of-the-nation book, a satirical comedy of metropolitan literary life, a sweeping, Dickensian look at contemporary London, a serious examination of Islam and the reasons for radicalism among young Muslims, a thriller, a satire on the Notting Hill Cameroonians and a detailed look at the sharp financial practices that led to the collapse. There's London football, reality TV, cyber porn, a love story or two. As if all that weren't enough, it is a roman a clef, which has already provided fun for metropolitan journalists as they speculate about the identity of the various characters.

A Week in December. Sebastian Faulks

pp400,Hutchinson,£18.99

The scene is set with the wife of a Tory MP organising a dinner party for the benefit of her husband's career in somewhere evoking Notting Hill. Every guest is chosen to suggest that the MP is a Renaissance man. We are reminded of Alan Hollinghurst's The Line of Beauty, as though all wealthy Tories inevitably have grand gatherings with deep undercurrents of class, ambition and financial chicanery. As she goes through the guest list, we immediately know that they are all going to be linked in some way. The guests are mostly wealthy men and their wives, owners of hedge funds and banks and so on.

There is also a manufacturer who has been invited to lend multicultural credibility. Farooq al-Rashid has made his money in pickles; he is a substantial contributor to the party and he has a son – the alarm bells ring stridently at this point – called Hassan who, in his parents' opinion, is rather too interested in the true message of Islam. While they simply want to enjoy the benefits of wealth and acceptance, he is planning to blow the Kafir world to pieces.

John Veals is a hedge fund owner who has made hundreds of millions by barely legal activity and he sees an opportunity to make much, much more by causing a big bank to collapse. Faulks has clearly done extensive research, sometimes not wholly digested by the plot, but admirably authentic. The real problem with Veals, though, is that he never lifts off the page. This is partly because the book is so crowded that Faulks doesn't have the space to produce a rounded character. Any novel that tries to take the temperature of the nation needs a fully human central character to pull the big themes together. Dickens's Merdle and Tom Wolfe's Sherman McCoy are horribly believable.

Anyway, besides the toffs, there are two less plutocratic guests invited to the dinner party, one an unsuccessful and bookish young barrister, Gabriel Northwood, the other a jobbing literary journalist, R Tranter. Tranter is all too clearly based on journalist DJ Taylor. Tranter admires Thackeray and writes for a satirical magazine, the Toad; Taylor has written a biography of Thackeray and writes a literary column for Private Eye. Tranter uses the Toad to work out his disdain for, and envy of, more successful writers. He also has a habit in his reviews of sadly concluding that most successful authors are ultimately deploying a few cheap tricks and are con artists, even if they are good. His reaction when he reads a novel by a rival critic – "It was worse, far worse, than he had dared to hope" – is spot on. There is a brilliant literary prize scene which was painfully familiar to me. Faulks knows the book world and satirises it with brio, but he can give up any hope of winning the Costa Prize after this.

The marriage of these elements is mostly smooth, with the best strands involving the literary world and the hypocrisies and presumption of the rich. Less successful is Faulks's rather plodding analysis of why young men turn to Islam. All too often, we are subjected to reiterations of the contradictions of the Qur'an and Islam's appeal to the disaffected, which are strangely lifeless as fiction. In John Updike's 2006 novel , the conversations between the potential bomber and his mentor also suffered from a certain stiffness. Maybe it is difficult to cross this particular cultural barrier. Another key character, Jenni Fortune (not invited to the dinner party), is a book-loving, cyber-obsessed young tube driver; her world isn't fully realised either.

But Gabriel Northwood, the barrister, is a fine character. He is slightly diffident, very human in his weaknesses, observant and well read. Remembering the great love of his life, a married woman, Northwood wonders about "this desperate passion… was it really such an enviable way to live, always at the edge of panic, desperate for a cellphone bleep, all your judgments skewed?" Some time before the book opens, he met Jenni, when he was junior to a QC on a case involving London Transport: Jenni had been driving a train when somebody jumped on to the line. He has taken to seeing her on the slightest pretext; we know that they are going to fall in love, despite their different backgrounds.

As the week progresses, we see Farooq al-Rashid preparing for his investiture with the OBE at Buckingham Palace; he is fretting over what he is going to say to the Queen. For a few months, he has been employing Tranter to coach him on the Queen's literary preferences. At their first meeting, Tranter dismissed all the books Rashid had been advised to buy ("OT – Oirish Twaddle", the "higher bogus", "poor man's Somerset Maugham" or "from the man who put the anal into banal") and recommended instead an obscure Victorian writer and Dick Francis.

In a highly nervous state, Rashid is trying to memorise the verdicts Tranter delivered in case Her Majesty should ask him what he reads. Meanwhile, young Hassan has to juggle his timetable in order to go on from Buckingham Palace to the bombing of a hospital with a large maternity unit. The scene at the investiture is hilarious, particularly as Prince Charles stands in for his mother. One of the flunkeys, as he boxes up Farooq's medal, says: "How was the Princess? She's ever such a chatterbox when she gets going. There you are, sir. One little gong."

As John Veals puts the finishing touches to his plan to bring down a bank – and incidentally destroy the livelihoods of thousands of African farmers – his teenage son, Finbar, is experimenting with skunk. This leads to a terrible psychotic episode and admission to hospital where it is touch and go if he will recover or lapse into schizophrenia. His mother, Vanessa, ultimately comes to his aid, overcome by guilt for her neglect.

Finally, the dinner party takes place. One of the guests, Roger Malpasse, delivers a fine drunken rant against the financial malpractice that is leading to crisis: "It's a fraud as old as markets themselves. The only difference is that it's been done on a titanic scale. At the invitation of the politicians. Behind the backs of the regulators and with the dumb connivance of the auditors. And with the fatal misunderstanding of the ratings agencies." This is one of the strongest moments in the novel, and unexpected, because up to now Roger has been portrayed only as a man who likes a drink, starting with a "phlegm-cracker" early in the day, moving on to a "sharpener" before food and finishing with a "zonker", which is virtually anything he can tip into a glass at the end of the day.

A Week in December is a little too long, a little too prolix. And yet it survives all this to be a compelling tale of contemporary London. I am not sure that it is the classic state-of-the-nation novel we need, but I have no doubt at all that it will outsell the higher bogus by a very long way.

Sebastian Faulks

Born 20 April 1953 and later educated at Emmanuel College, Cambridge. Now lives with his wife, Victoria, and three children in west London.

1984 His first published novel, A Trick of the Light

1986 Appointed the first literary editor of the Independent, then deputy editor of the Independent on Sunday

1989 The Girl at the Lion d'Or, the first of his French Trilogy, is published.

1993 Birdsong published.

1998 Charlotte Gray wins the James Tait Black Memorial Prize and is made into a film starring Cate Blanchett.

2006 Publishes the non-fiction Pistache, a series of parodies of other writers.

2008 Writes Devil May Care, a new James Bond novel to mark the centenary of Ian Fleming's birth.

2002 Made a CBE and in 2007 an honorary fellow of Emmanuel College.

He says: "I found it extremely difficult to get going as a novelist."

They say: "A masterpiece, one of the great novels of this or any other century." Trevor Nunn on Human Traces (2005). Oliver Marre

Saturday, February 20, 2010

Wartime trickery and misdirection

Five Best: The British talent for wartime trickery and misdirection is fully revealed by these books, says Nicholas Rankin

1. 'Blinker' Hall. (2008). David Ramsay. Stroud : Spellmount. 940.459

As David Ramsay recounts in this fascinating biography, Britain's Machiavellian director of naval intelligence in World War I, Reginald "Blinker" Hall, was a man whose talent for tricks and bribes made the U.S. ambassador consider him "the one genius that the war has developed." Hall's organization, working out of Room 40 in the Admiralty offices, "tapped the air" for German wireless messages and scanned diplomatic cables. The codebreakers' greatest coup came in 1917 with the interception and deciphering of "the Zimmermann telegram," a secret message from Germany to the Mexican government offering money and the return of the American Southwest if the Mexicans would help wage war on the U.S. The furor that ensued after the message's contents were revealed helped impel the U.S. into the war, thus clinching final victory for the British and their allies.

2. The Double-Cross System in the War of 1939 to 1945. (1972). J.C. Masterman. New Haven: Yale. 940.5486 M

J.C. Masterman was an Oxford don who, during World War II, chaired the secret Twenty Committee—20 is XX in Roman numerals, but XX is also a "double cross." The group coordinated false information fed to German intelligence through Nazi spies who had been "turned." Masterman waited nearly three decades after the war's end to publish his account of how the committee and more generally the British Security Service (also known as MI5) actively ran and controlled agents of the German espionage service, but his book caused a sensation nonetheless. It was the first great, unsanctioned breach in the wall of British wartime secrecy. As an operating handbook of astonishingly successful deception, "The Double-Cross System" is without peer. But some of Masterman's colleagues never spoke to him again for having exposed their work.

3. The Man Who Never Was. (1953). Ewen Montagu. Philadelphia: Lippincott. 940.5486 M

Operation Mincemeat, designed to divert German attention away from the Allies' impending invasion of Sicily in 1943, involved planting false papers on a genuine corpse outfitted to be a British Royal Marine, "Maj. William Martin." The body was dropped in the ocean off the coast of Spain; when it washed ashore, the Germans soon discovered what seemed to be plans for an invasion of Greece and Sardinia. Mincemeat worked perfectly—the Nazis took the poisoned bait and rushed to bolster their Greek defenses. A novel published soon after World War II told the tale of the operation, but readers had no idea how close to the truth the improbable story was until the appearance a few years later of "The Man Who Never Was." Lawyer Ewen Montagu, who had been the naval-intelligence representative on the Twenty Committee during the war, was given official permission to write the book after a reporter began digging for the half-buried facts in the fictional version. Montagu produced a genuine wartime thriller.

4. The Deceivers. (2004). Thaddeus Holt. New York: Scribner. 940.5486 H

This scholarly yet entertaining magnum opus is the definitive account of all the stratagems used by the Allies against the Axis in World War II. The "master of the game" was the enigmatic Britisher Brig. Dudley W. Clarke, and "The Deceivers" follows the development of Clarke's organization, from its origins in a converted bathroom in Cairo to a world-wide network with key nodes in Washington, London and New Delhi. It was during the desert warfare in North Africa that Clarke started using such ruses as dummy vehicles and fake radio traffic to make the enemy think the British were stronger than they were. The culmination of these ideas was the big lie that convinced the German high command in 1944 that the Allied invasion of Europe would come not at Normandy but with an Army Group led by Gen. George S. Patton at Calais.

5. Garbo. Tomás Harris. (2000). Kew: Public Record Office. 940.54 H

Catalan-born Juan Pujol— the greatest of World War II double agents—was such a brilliant actor that British intelligence gave him the codename Garbo. The Germans, who thought Pujol was working for them, called him Arabel (sometimes Arabal). His exploits were recorded by his handler, Tomás Harris, in an intelligence file that made such riveting reading that it was published in book form. It shows how Pujol and Harris collaborated in creating a network of fictitious sub-agents throughout Britain to channel bogus information through "Arabel" to the enemy. His ultimate coup was playing a key role in persuading the Germans to hold troops ready for the imminent D-Day invasion at Calais. During the war the oblivious Germans gratefully awarded the Iron Cross to Pujol; after the war, he was given the Order of the British Empire (fifth class) and a gratuity that allowed him to retire quietly to Venezuela, where he died in 1988.

—Mr. Rankin is the author of "A Genius for Deception: How Cunning Helped the British Win Two World Wars" (2009). New York: Oxford.

1. 'Blinker' Hall. (2008). David Ramsay. Stroud : Spellmount. 940.459

As David Ramsay recounts in this fascinating biography, Britain's Machiavellian director of naval intelligence in World War I, Reginald "Blinker" Hall, was a man whose talent for tricks and bribes made the U.S. ambassador consider him "the one genius that the war has developed." Hall's organization, working out of Room 40 in the Admiralty offices, "tapped the air" for German wireless messages and scanned diplomatic cables. The codebreakers' greatest coup came in 1917 with the interception and deciphering of "the Zimmermann telegram," a secret message from Germany to the Mexican government offering money and the return of the American Southwest if the Mexicans would help wage war on the U.S. The furor that ensued after the message's contents were revealed helped impel the U.S. into the war, thus clinching final victory for the British and their allies.

2. The Double-Cross System in the War of 1939 to 1945. (1972). J.C. Masterman. New Haven: Yale. 940.5486 M

J.C. Masterman was an Oxford don who, during World War II, chaired the secret Twenty Committee—20 is XX in Roman numerals, but XX is also a "double cross." The group coordinated false information fed to German intelligence through Nazi spies who had been "turned." Masterman waited nearly three decades after the war's end to publish his account of how the committee and more generally the British Security Service (also known as MI5) actively ran and controlled agents of the German espionage service, but his book caused a sensation nonetheless. It was the first great, unsanctioned breach in the wall of British wartime secrecy. As an operating handbook of astonishingly successful deception, "The Double-Cross System" is without peer. But some of Masterman's colleagues never spoke to him again for having exposed their work.

3. The Man Who Never Was. (1953). Ewen Montagu. Philadelphia: Lippincott. 940.5486 M

Operation Mincemeat, designed to divert German attention away from the Allies' impending invasion of Sicily in 1943, involved planting false papers on a genuine corpse outfitted to be a British Royal Marine, "Maj. William Martin." The body was dropped in the ocean off the coast of Spain; when it washed ashore, the Germans soon discovered what seemed to be plans for an invasion of Greece and Sardinia. Mincemeat worked perfectly—the Nazis took the poisoned bait and rushed to bolster their Greek defenses. A novel published soon after World War II told the tale of the operation, but readers had no idea how close to the truth the improbable story was until the appearance a few years later of "The Man Who Never Was." Lawyer Ewen Montagu, who had been the naval-intelligence representative on the Twenty Committee during the war, was given official permission to write the book after a reporter began digging for the half-buried facts in the fictional version. Montagu produced a genuine wartime thriller.

4. The Deceivers. (2004). Thaddeus Holt. New York: Scribner. 940.5486 H

This scholarly yet entertaining magnum opus is the definitive account of all the stratagems used by the Allies against the Axis in World War II. The "master of the game" was the enigmatic Britisher Brig. Dudley W. Clarke, and "The Deceivers" follows the development of Clarke's organization, from its origins in a converted bathroom in Cairo to a world-wide network with key nodes in Washington, London and New Delhi. It was during the desert warfare in North Africa that Clarke started using such ruses as dummy vehicles and fake radio traffic to make the enemy think the British were stronger than they were. The culmination of these ideas was the big lie that convinced the German high command in 1944 that the Allied invasion of Europe would come not at Normandy but with an Army Group led by Gen. George S. Patton at Calais.

5. Garbo. Tomás Harris. (2000). Kew: Public Record Office. 940.54 H

Catalan-born Juan Pujol— the greatest of World War II double agents—was such a brilliant actor that British intelligence gave him the codename Garbo. The Germans, who thought Pujol was working for them, called him Arabel (sometimes Arabal). His exploits were recorded by his handler, Tomás Harris, in an intelligence file that made such riveting reading that it was published in book form. It shows how Pujol and Harris collaborated in creating a network of fictitious sub-agents throughout Britain to channel bogus information through "Arabel" to the enemy. His ultimate coup was playing a key role in persuading the Germans to hold troops ready for the imminent D-Day invasion at Calais. During the war the oblivious Germans gratefully awarded the Iron Cross to Pujol; after the war, he was given the Order of the British Empire (fifth class) and a gratuity that allowed him to retire quietly to Venezuela, where he died in 1988.

—Mr. Rankin is the author of "A Genius for Deception: How Cunning Helped the British Win Two World Wars" (2009). New York: Oxford.

Labels:

Book review,

Books,

England,

Spies,

WW2

Tuesday, February 2, 2010

Browning's Aeschylus

A very English film. Finney plays a hard-ass teacher who gives not an inch on his demands that his students learn the classics in Greek. For varied reasons, he has been forced out after 18 years, and not given a pension. Scacchi plays his not-loving wife, who is having an affair with another teacher in the private school where they all work.

Enjoyable.

Enjoyable.

Sunday, January 24, 2010

Enchanted April

Two English wives search for an escape from the dreariness of unhappy marriages, and go to a castle on the Italian coast for the month of April. Based on a book by Elizabeth von Arnim.

Lottie Wilkins (played by Josie Lawrence - whom, at first, I did not recognize, byt soon realized I remembered from the English , and original, version of Whose line is it anyway?) sees a newspaper advert for an Italian castle being let for April, with servants, and decides she wants to go. In her ladies club she speaks with Rose Arbuthnot (played by Miranda Richardson), and convinces her that the month's respite would do them good. Soon Mrs. Arbuthnot is in charge of the details, and rents the castle from George Briggs (played by Michael Kitchen, of Foyle's War). To offset the cost of the month's rent, they advertise for women to share their month's idyll, and receive, to their utter surprise, only two answers. One is crusty Mrs. Fisher (played by Joan Plowright), a widow whose husband had been part of English intellectual circles in which personages such as Tennyson existed, and who retains a rather elevated sense of herself. The second respondent is Lady Caroline Dester (played by Polly Walker), a society beauty who longs to be away from all the attention of men clawing at her, all the parties she attends, and simply do nothing.

It was a kick to see Joan Plowright, the reason I searched out the film (being on a Plowright binge, having seen Mrs. Palfrey at the Claremont and Tea with Mussolini recently). An added fun detail was the presence of an Arbuthnot, as there had been a charactert with the same name in Claremont. She plays the character marvelously, and some of her quirks and mannerisms, and vocal inflections, are there.

The Italian countryside is a marvelous added detail. The men in the film, Alfred Molina playing Mellersh Wilkins, Michael Kitchen as George Briggs, and Jim Broadbent as Frederick Arbuthnot, are quite hapless.

A gem.

Lottie Wilkins (played by Josie Lawrence - whom, at first, I did not recognize, byt soon realized I remembered from the English , and original, version of Whose line is it anyway?) sees a newspaper advert for an Italian castle being let for April, with servants, and decides she wants to go. In her ladies club she speaks with Rose Arbuthnot (played by Miranda Richardson), and convinces her that the month's respite would do them good. Soon Mrs. Arbuthnot is in charge of the details, and rents the castle from George Briggs (played by Michael Kitchen, of Foyle's War). To offset the cost of the month's rent, they advertise for women to share their month's idyll, and receive, to their utter surprise, only two answers. One is crusty Mrs. Fisher (played by Joan Plowright), a widow whose husband had been part of English intellectual circles in which personages such as Tennyson existed, and who retains a rather elevated sense of herself. The second respondent is Lady Caroline Dester (played by Polly Walker), a society beauty who longs to be away from all the attention of men clawing at her, all the parties she attends, and simply do nothing.

It was a kick to see Joan Plowright, the reason I searched out the film (being on a Plowright binge, having seen Mrs. Palfrey at the Claremont and Tea with Mussolini recently). An added fun detail was the presence of an Arbuthnot, as there had been a charactert with the same name in Claremont. She plays the character marvelously, and some of her quirks and mannerisms, and vocal inflections, are there.

The Italian countryside is a marvelous added detail. The men in the film, Alfred Molina playing Mellersh Wilkins, Michael Kitchen as George Briggs, and Jim Broadbent as Frederick Arbuthnot, are quite hapless.

A gem.

Wednesday, January 20, 2010

Ladies in Lavender

Maggie Smith and Judi Dench play two sisters living in splendid isolation in Cornwall. One day they find a body washed up on the beach, who turns out to be Andrea, a Polish musician who washed up on shore (it is never fully explained how or why that happened). The sisters become fond of Andrea: Janet (Smith) becomes a somewhat remote mother figure, who speaks enough German to communicate with the young man; Ursula (Dench) becomes infatuated with him, the love she has never had for anyone now directed to Andrea. The local doctor at first treats the youngster, then becomes resentful of his presence, and finally jealous of him. A young Russian woman, Olga, is in town, painting, and rebuffs the doctor's romantic advances. It is then that the doctor tells the local police that he suspects the foreigners in their midst. Olga tells Andrea that he is a very talented violinist, and wishes him to meet her brother, a concert violinist and conductor.

Dench and Smith do their usual great work.

Dench and Smith do their usual great work.

Brief Encounter

Watched film in two parts: started it last Thursday evening, finished it last evening (before watching Mrs. Palfrey yet again).

Rather slow. Melodramatic. Yet I managed to enjoy it. Rachmaninoff's

Piano Concerto No. 2 played by Eileen Joyce, runs through the film.

Trevor Howard and Celia Johnson

Rather slow. Melodramatic. Yet I managed to enjoy it. Rachmaninoff's

Piano Concerto No. 2 played by Eileen Joyce, runs through the film.

Trevor Howard and Celia Johnson

Thursday, January 14, 2010

Feature films as history

Selected papers from a conference sponsored by Zentrum für Interdisziplinäre Forschung, University of Bielefeld held in 1979.

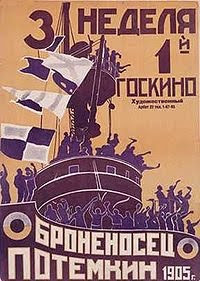

Cover of book shows "Jacket illustration of Battleship Potemkin poster from the National Film Archive, London" of a sailor with the ship's name on the headband of his cap.

The book contains papers on:

1. Introduction: Feature films as history

2. Battleship Potemkin

3. Germany and France in 1920s

4. Jean Renoir

5. British films, 1935-1947

6. Film censorship in Liberal England

7. Casablanca, Tennessee Johnson and The Negro Soldier

8. Hollywood fights anti-Semitism

Cover of book shows "Jacket illustration of Battleship Potemkin poster from the National Film Archive, London" of a sailor with the ship's name on the headband of his cap.

The book contains papers on:

1. Introduction: Feature films as history

2. Battleship Potemkin

3. Germany and France in 1920s

4. Jean Renoir

5. British films, 1935-1947

6. Film censorship in Liberal England

7. Casablanca, Tennessee Johnson and The Negro Soldier

8. Hollywood fights anti-Semitism

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)