Jack London is known as the writer of what are now children's books, about animals, mainly. Yet, as is usual, there is more to him than the simple image. This review is fascinating: Theroux chastices Haley for obsessing over London's possible homosexuality, yet calls it still a valuable London biography.

Back From the Beyond

The author known for 'The Call of the Wild' was a man of protean passions

By Alexander Theroux

Jack London, born John Griffith Chaney in 1876, grew up a working-class, fatherless boy in Oakland, Calif., and spent his teen years riding the rails, thieving oysters, sailing on a seal-hunting schooner and toiling as what he would later call a "work beast," shoveling coal, working in a cannery, loading bobbins in a jute mill, ironing shirts in a steam laundry. Somehow he also found time to spend in libraries and became an enthusiastic reader of novels and travel books at an early age.

Jack London at his desk in 1916, the year he died at age 40.

On the sealing schooner in 1873 he had survived a harrowing run-in with a typhoon. The stories he told about the storm after his return home prompted his mother, when she saw the announcement of a writing contest in the San Francisco Morning Call asking for descriptive articles by local writers 22 years old or younger, to urge her son to write up his typhoon experience for the contest. The 17-year-old London won the $25 first prize, "beating out students from Stanford and Berkeley with his eighth-grade education," writes biographer James L. Haley in "Wolf: The Lives of Jack London." The prize money, Mr. Haley notes, was the equivalent of a month's wages in the London household. "Jack London, author, was born."

The young man plunged into writing short stories—but found that he couldn't sell them. He made a trip to the East Coast in 1874 (spending a month unjustly jailed as a vagrant in Buffalo), returned to Oakland and enrolled at the University of California at Berkeley, only to withdraw after a semester. Hearing news of a gold strike in the Canadian Yukon Territory, he was hit by a case of "Klondicitis" and headed north. He came back flat broke at 22, more determined than ever to make a living as a writer. London's first-hand experience of life in America's penniless subculture turned him into a committed socialist for the rest of his life—which was not all that long. He died at age 40; during the intervening two decades he would become the highest-paid writer in the country.

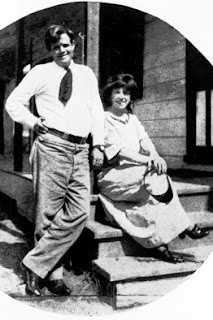

Mr. London with his wife, Charmian, in an undated photograph.

The book that made him a national celebrity, at age 27, was "The Call of the Wild," a novel about a domesticated dog that eventually finds its true self in the raw life of a sled dog in the Yukon. Suddenly it seemed that London knew everybody in the writing world. Sinclair Lewis, Ambrose Bierce, Emma Goldman, Upton Sinclair, Lincoln Steffens, Ida Tarbell and many others counted the young, red-blooded author as their friend.

Mr. Haley says that he does not intend, with "Wolf," to recapitulate what has already been written about London, whether in adulatory biographies or lit-crit monographs. The author wants to explore the forgotten, the "real" Jack London, concluding that "what London needs is a biographer's eye—not the eye of a vestal flametender, nor an acolyte, nor a revisionist, but a biographer's eye, from totally outside the existing circle." Thus we are treated to portraits of London's father, William Chaney, an itinerant evangelizing astrologer; of his shrewish mother, Flora Wellman, a woman who was born into wealth in Ohio and fled both; and of John London, a Civil War veteran from Pennsylvania who married Flora when London was eight months old, giving her a "chance at respectability."

We also meet London's demanding, unforgiving first wife, Bessie, and their two daughters; his African- American wet nurse, a splendid force in his life, named Virginia Prentiss; and, notably, the lusty and lovely but often traduced Charmian Kittredge, the offspring of parents who had dabbled in free love, whom London married on a lecture tour in Chicago in 1906.

Prolific, irrepressible, madly energetic, London wrote a thousand words a day without fail, compulsively, whether or not he was inspired. At his peak he often wrote as many as two books a year. In 1913 alone he published the story collection "The Night Born," two novels ("The Abysmal Brute" and "The Valley of the Moon"), along with his famous "alcoholic memoir" "John Barleycorn," in which he confessed to a lifelong struggle with booze. Temperance advocates used "John Barleycorn" in their push for prohibition; liquor companies denounced it; a popular movie was made of it; ministers cited it in sermons.

London lived hard and intensely, and the plural "lives" to which Mr. Haley refers in the book's subtitle sound plausible. London was a reporter as well as a novelist—Hearst paid him to cover the Russo-Japanese War in 1904—and traveled to the far ends of the planet. He was an omnivorous reader. On cross-country jaunts he lectured about the evils of capitalism. He ate indiscriminately (raw pressed duck was a favorite) and smoked cigarettes until the end of his life. A free spirit, he loved bicycling, flying kites and listening to music—Charmian was a virtuoso pianist. Having traveled to Hawaii and surfed "until the tropical sun almost killed him," London "introduced the sport to the world" in 1911 with "The Cruise of the Snark," an account of a Pacific sailing expedition.

Although London was famous for depicting the brutality of nature in his work, he also celebrated animals in novels such as "The Sea-Wolf" and "White Fang" and was tender-hearted toward them in life. London owned a California ranch, where he kept horses, dogs and pigs. Upon seeing a bullfight in Quito, Ecuador, in 1909, he found it so revolting that he excoriated the sport in his story "The Madness of John Harned." London wept at the deaths of his pets.

The common picture of London presents a robustly physical man with, sadly for Charmian, an almost athletic enthusiasm for philandering. But Mr. Haley wants to give us the "real" Jack London, and so—perhaps inevitably, given the times we live in and the nature of contemporary literary biography—we are treated to endless speculation about London's possible homosexuality. In a July 1903 letter to Charmian, written on the cusp of their marriage and obviously seeking her sympathy, London laments that he has "never had a comrade" and yearns for a "great Man-Comrade" who should be "so much one with me that we could never misunderstand," adding: "He should love the flesh, as he should the spirit."

[BK_Cover2]

Wolf: The Lives of Jack London

By James L. Haley

Basic Books, 364 pages, $29.95

* Read an excerpt

Mr. Haley makes much of this. He also focuses attention on London's friendship with the poet George Sterling. London called him the "Greek" on account of his classical good looks; Sterling called him Wolf. The two were indeed close. Sterling's editorial gifts influenced "The Call of the Wild," and Charmian, before the marriage, fretted about how much time London spent with his friend.

It wouldn't have been the first time that a fiancée resented her intended's pals, but Mr. Haley sees something more. "Sterling alone held the potential to embrace a soul as vast and complex as his own," he writes. "London was never bashful about recommending the therapeutic value of recreational sex, and Sterling was equally forthright in his contention that orgasms liberated creativity. Although the most noted affairs of both men were certainly with women, it seems not improbable that Wolf and the Greek found time and circumstance for one another, but neither man ever committed to paper how deep their relationship extended." Readers can be pardoned for thinking it seems not improbable that London, given the chance, would punch Mr. Haley in the nose.

Mr. Haley is almost prurient with his gaydar. He speculates on the nature of male comradeship during the 17-year-old London's sealing trip to Japan. The author finds homosexual undertones in the brutal naturalism of "The Sea-Wolf." In London's boxing novel, "The Game," Mr. Haley finds "surprisingly" lyrical descriptions of male beauty, stripped and muscular, and he raises an eyebrow over photographs of London "minimally-clad" in "he-man poses." London "was proud of his blond-beastly body," we're told, "and was not shy about showing it off. Unpublished nudes of him also exist."

Mr. Haley concedes—it feels grudging—that he has no solid evidence for London's homosexuality, yet he insists on keeping the theme alive throughout the book. That misguided decision mars "Wolf" (as does, in a minor way, the author's maddening misuse of the word "disinterest"). But this is still a valuable London biography. It surpasses Irving Stone's 1938 "Sailor on Horseback," giving us a well-delineated picture of a singular, complicated figure, a socialist who signed his letters "Yours for the revolution, Jack London" but who traveled for decades—often first-class—with an Asian servant who was required to call him "Master." London was an anti-capitalist who wildly speculated in schemes like importing and selling Australian eucalyptus trees in hopes that he would make a killing as they replaced Eastern hardwoods—in one season he planted 16,000 of them. He was a polemicist who pleaded for the waifs in London but built a four-story castle on the extravagant 1,000-acre Beauty Ranch near Glen Ellen, Calif. "His socialism was not about banning wealth," Mr. Haley notes. "It was about banning wealth accrued by exploiting others."

These days we have little sense of the literary glory that Jack London. When he is read at all, it is predominantly as a writer of boy's books. The daring novel he wrote in 1907, "Before Adam," is a fiercely imaginative, Darwinian tale about a caged lion in a circus, and it is fascinating in its exploration of atavistic memory. The book sold 65,000 copies a century ago but is virtually unknown today. Thanks to James Haley's zeal, the author of that novel, not just the man of "The Call of the Wild" fame, is before us again.

—Mr. Theroux's latest novel is "Laura Warholic: Or, The Sexual Intellectual" (Fantagraphics).

Thursday, May 20, 2010

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Blog Archive

-

▼

2010

(170)

-

▼

May

(21)

- The lemon tree

- 5 moguls

- How the West won

- Sjöwall and Wahlöö

- Aimée & Jaguar : a love story, Berlin 1943

- A man of protean passions

- Books on Statesmen

- The Red Book Of C.G. Jung

- Blame it on the rain

- The truth about dogs

- Operation Mincemeat

- Capitalist democracy crisis

- The Jewish Question

- The Man Who Broke Babe’s Record

- Ghost town

- Five Best Baseball Books

- Bedwetter

- Literature About Aging

- Successful Spadework

- Fun with Dick & Jane

- The things they carried

-

▼

May

(21)

No comments:

Post a Comment