Jack London is known as the writer of what are now children's books, about animals, mainly. Yet, as is usual, there is more to him than the simple image. This review is fascinating: Theroux chastices Haley for obsessing over London's possible homosexuality, yet calls it still a valuable London biography.

Back From the Beyond

The author known for 'The Call of the Wild' was a man of protean passions

By Alexander Theroux

Jack London, born John Griffith Chaney in 1876, grew up a working-class, fatherless boy in Oakland, Calif., and spent his teen years riding the rails, thieving oysters, sailing on a seal-hunting schooner and toiling as what he would later call a "work beast," shoveling coal, working in a cannery, loading bobbins in a jute mill, ironing shirts in a steam laundry. Somehow he also found time to spend in libraries and became an enthusiastic reader of novels and travel books at an early age.

Jack London at his desk in 1916, the year he died at age 40.

On the sealing schooner in 1873 he had survived a harrowing run-in with a typhoon. The stories he told about the storm after his return home prompted his mother, when she saw the announcement of a writing contest in the San Francisco Morning Call asking for descriptive articles by local writers 22 years old or younger, to urge her son to write up his typhoon experience for the contest. The 17-year-old London won the $25 first prize, "beating out students from Stanford and Berkeley with his eighth-grade education," writes biographer James L. Haley in "Wolf: The Lives of Jack London." The prize money, Mr. Haley notes, was the equivalent of a month's wages in the London household. "Jack London, author, was born."

The young man plunged into writing short stories—but found that he couldn't sell them. He made a trip to the East Coast in 1874 (spending a month unjustly jailed as a vagrant in Buffalo), returned to Oakland and enrolled at the University of California at Berkeley, only to withdraw after a semester. Hearing news of a gold strike in the Canadian Yukon Territory, he was hit by a case of "Klondicitis" and headed north. He came back flat broke at 22, more determined than ever to make a living as a writer. London's first-hand experience of life in America's penniless subculture turned him into a committed socialist for the rest of his life—which was not all that long. He died at age 40; during the intervening two decades he would become the highest-paid writer in the country.

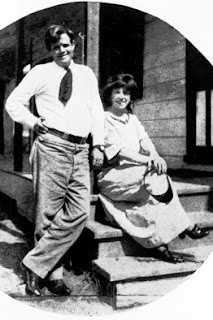

Mr. London with his wife, Charmian, in an undated photograph.

The book that made him a national celebrity, at age 27, was "The Call of the Wild," a novel about a domesticated dog that eventually finds its true self in the raw life of a sled dog in the Yukon. Suddenly it seemed that London knew everybody in the writing world. Sinclair Lewis, Ambrose Bierce, Emma Goldman, Upton Sinclair, Lincoln Steffens, Ida Tarbell and many others counted the young, red-blooded author as their friend.

Mr. Haley says that he does not intend, with "Wolf," to recapitulate what has already been written about London, whether in adulatory biographies or lit-crit monographs. The author wants to explore the forgotten, the "real" Jack London, concluding that "what London needs is a biographer's eye—not the eye of a vestal flametender, nor an acolyte, nor a revisionist, but a biographer's eye, from totally outside the existing circle." Thus we are treated to portraits of London's father, William Chaney, an itinerant evangelizing astrologer; of his shrewish mother, Flora Wellman, a woman who was born into wealth in Ohio and fled both; and of John London, a Civil War veteran from Pennsylvania who married Flora when London was eight months old, giving her a "chance at respectability."

We also meet London's demanding, unforgiving first wife, Bessie, and their two daughters; his African- American wet nurse, a splendid force in his life, named Virginia Prentiss; and, notably, the lusty and lovely but often traduced Charmian Kittredge, the offspring of parents who had dabbled in free love, whom London married on a lecture tour in Chicago in 1906.

Prolific, irrepressible, madly energetic, London wrote a thousand words a day without fail, compulsively, whether or not he was inspired. At his peak he often wrote as many as two books a year. In 1913 alone he published the story collection "The Night Born," two novels ("The Abysmal Brute" and "The Valley of the Moon"), along with his famous "alcoholic memoir" "John Barleycorn," in which he confessed to a lifelong struggle with booze. Temperance advocates used "John Barleycorn" in their push for prohibition; liquor companies denounced it; a popular movie was made of it; ministers cited it in sermons.

London lived hard and intensely, and the plural "lives" to which Mr. Haley refers in the book's subtitle sound plausible. London was a reporter as well as a novelist—Hearst paid him to cover the Russo-Japanese War in 1904—and traveled to the far ends of the planet. He was an omnivorous reader. On cross-country jaunts he lectured about the evils of capitalism. He ate indiscriminately (raw pressed duck was a favorite) and smoked cigarettes until the end of his life. A free spirit, he loved bicycling, flying kites and listening to music—Charmian was a virtuoso pianist. Having traveled to Hawaii and surfed "until the tropical sun almost killed him," London "introduced the sport to the world" in 1911 with "The Cruise of the Snark," an account of a Pacific sailing expedition.

Although London was famous for depicting the brutality of nature in his work, he also celebrated animals in novels such as "The Sea-Wolf" and "White Fang" and was tender-hearted toward them in life. London owned a California ranch, where he kept horses, dogs and pigs. Upon seeing a bullfight in Quito, Ecuador, in 1909, he found it so revolting that he excoriated the sport in his story "The Madness of John Harned." London wept at the deaths of his pets.

The common picture of London presents a robustly physical man with, sadly for Charmian, an almost athletic enthusiasm for philandering. But Mr. Haley wants to give us the "real" Jack London, and so—perhaps inevitably, given the times we live in and the nature of contemporary literary biography—we are treated to endless speculation about London's possible homosexuality. In a July 1903 letter to Charmian, written on the cusp of their marriage and obviously seeking her sympathy, London laments that he has "never had a comrade" and yearns for a "great Man-Comrade" who should be "so much one with me that we could never misunderstand," adding: "He should love the flesh, as he should the spirit."

[BK_Cover2]

Wolf: The Lives of Jack London

By James L. Haley

Basic Books, 364 pages, $29.95

* Read an excerpt

Mr. Haley makes much of this. He also focuses attention on London's friendship with the poet George Sterling. London called him the "Greek" on account of his classical good looks; Sterling called him Wolf. The two were indeed close. Sterling's editorial gifts influenced "The Call of the Wild," and Charmian, before the marriage, fretted about how much time London spent with his friend.

It wouldn't have been the first time that a fiancée resented her intended's pals, but Mr. Haley sees something more. "Sterling alone held the potential to embrace a soul as vast and complex as his own," he writes. "London was never bashful about recommending the therapeutic value of recreational sex, and Sterling was equally forthright in his contention that orgasms liberated creativity. Although the most noted affairs of both men were certainly with women, it seems not improbable that Wolf and the Greek found time and circumstance for one another, but neither man ever committed to paper how deep their relationship extended." Readers can be pardoned for thinking it seems not improbable that London, given the chance, would punch Mr. Haley in the nose.

Mr. Haley is almost prurient with his gaydar. He speculates on the nature of male comradeship during the 17-year-old London's sealing trip to Japan. The author finds homosexual undertones in the brutal naturalism of "The Sea-Wolf." In London's boxing novel, "The Game," Mr. Haley finds "surprisingly" lyrical descriptions of male beauty, stripped and muscular, and he raises an eyebrow over photographs of London "minimally-clad" in "he-man poses." London "was proud of his blond-beastly body," we're told, "and was not shy about showing it off. Unpublished nudes of him also exist."

Mr. Haley concedes—it feels grudging—that he has no solid evidence for London's homosexuality, yet he insists on keeping the theme alive throughout the book. That misguided decision mars "Wolf" (as does, in a minor way, the author's maddening misuse of the word "disinterest"). But this is still a valuable London biography. It surpasses Irving Stone's 1938 "Sailor on Horseback," giving us a well-delineated picture of a singular, complicated figure, a socialist who signed his letters "Yours for the revolution, Jack London" but who traveled for decades—often first-class—with an Asian servant who was required to call him "Master." London was an anti-capitalist who wildly speculated in schemes like importing and selling Australian eucalyptus trees in hopes that he would make a killing as they replaced Eastern hardwoods—in one season he planted 16,000 of them. He was a polemicist who pleaded for the waifs in London but built a four-story castle on the extravagant 1,000-acre Beauty Ranch near Glen Ellen, Calif. "His socialism was not about banning wealth," Mr. Haley notes. "It was about banning wealth accrued by exploiting others."

These days we have little sense of the literary glory that Jack London. When he is read at all, it is predominantly as a writer of boy's books. The daring novel he wrote in 1907, "Before Adam," is a fiercely imaginative, Darwinian tale about a caged lion in a circus, and it is fascinating in its exploration of atavistic memory. The book sold 65,000 copies a century ago but is virtually unknown today. Thanks to James Haley's zeal, the author of that novel, not just the man of "The Call of the Wild" fame, is before us again.

—Mr. Theroux's latest novel is "Laura Warholic: Or, The Sexual Intellectual" (Fantagraphics).

Showing posts with label American writers. Show all posts

Showing posts with label American writers. Show all posts

Thursday, May 20, 2010

Thursday, March 18, 2010

Steinbeck At 100

One more from my files, on Steinbeck, who remains my favorite writer. Interesting links, or links to interesting stories abound.One about his co-op on 72nd Streer finally going for sale in 2009, six years after Elaine Steinbeck's death, after apparent resolution of a bitter family feud.

Searching for a story from Newsday ("He's part of our heritage", written by Aileen Jacobson, took me to the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies in the ML King Library at San Jose State University.

Found a Facebook page entitled Travels with Stenbeck; neat.

March 19, 2002

ARTS IN AMERICA; The Pride Of Salinas: Steinbeck At 100

By STEPHEN KINZER

SALINAS, Calif.— Here in the fertile California valley that was home to many of the hobos, vagrants, prostitutes and migrant farm laborers who populate the works of John Steinbeck, a yearlong celebration is under way to honor the writer's memory.

There are also events being planned elsewhere, including New York, where Steinbeck lived for the last 18 years of his life. There is a tribute at Lincoln Center tonight, a conference at Hofstra University from Thursday through Saturday and a film series in April and May at City University. A Web site, http://www.steinbeck100.org/ newevents.html, provides information on events in other areas.

The Steinbeck towns like Salinas are no longer ringed by shantytowns filled with hungry Dust Bowl refugees, as in ''The Grapes of Wrath.'' Down the road in Monterey, the immigrants and ne'er-do-wells who populate books like ''Cannery Row'' and ''Tortilla Flat'' have given way to boutique owners.

Yet since Steinbeck's death, in 1968, people here have become zealous guardians of his legacy, so the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas seemed the appropriate place for the cake-cutting that opened what is to be a year of speeches, public readings, concerts, academic conferences, film showings and other tributes.

Steinbeck's works are still widely read in the United States and abroad. Many of his admirers say that is because he conveys a love of the downtrodden, the exploited, the ones he called ''the gathered and the scattered.'' He spent years living among them and portrayed them as deftly as any American writer ever has.

The celebration in Salinas on Feb. 27, the 100th anniversary of Steinbeck's birth, included the reading of official proclamations and the presentation of prizes to local high school students who have studied Steinbeck. It was one of more than 175 tributes to be held this year in 39 states. Together they are said to make up the largest-scale homage ever paid to an American author.

Many of these events are being paid for by the National Endowment for the Humanities, which gave $260,000 to a coalition of 26 nonprofit cultural groups and 100 local libraries.

The California Council for the Humanities is planning an effort to persuade as many Californians as possible to read ''The Grapes of Wrath'' over the summer. Beginning in October, libraries and schools across the state will sponsor discussion groups and other events related to the book.

''The Grapes of Wrath,'' generally considered Steinbeck's masterpiece, grew out of a newspaper assignment to investigate the living conditions in California of migrants from the parched heartland. He wrote it during an intense six-month creative marathon in 1938, and its graphic portrayal of workers suffering at the hands of callous landowners brought him death threats, an F.B.I. investigation and charges of Communist sympathy.

That last charge may have seemed plausible during the contentious 1930's, when anyone speaking out for the rights of the poor was considered suspicious, but it sounds quite odd in light of Steinbeck's later opinions. After World War II he denounced Communists for having ''established the most reactionary governments in the world, governments so fearful of revolt that they must make every man an informer against his fellows, and layer their society with secret police.'' During the 1960's he was one of the few American intellectuals who refused to denounce the United States role in Vietnam.

Steinbeck won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1962. ''His sympathies always go out to the oppressed, the misfits and the distressed,'' the Nobel committee asserted in choosing him. ''He likes to contrast the simple joy of life with the brutal and cynical craving for money.''

In accepting the award, Steinbeck said: ''The ancient commission of the writer has not changed. He is charged with exposing our many grievous faults and failures, with dredging up to the light our dark and dangerous dreams for the purpose of improvement. Furthermore, the writer is delegated to declare and to celebrate man's proven capacity for greatness of heart and spirit -- for gallantry in defeat, for courage, compassion and love.''

During Steinbeck's childhood in Salinas, his parents often read aloud to him and his three sisters. He spent hours in the attic of his family home devouring books like ''Adventures of Huckleberry Finn'' and ''Ivanhoe'' and one that became a lifelong favorite, Malory's ''Morte d'Arthur.''

As he grew older, Steinbeck often left Salinas and traveled to the seaside town of Monterey, about 25 miles away. There he developed a bond with cannery workers, fishermen and others on the fringes of society.

Most of Steinbeck's works are straightforward, accessible and easy to read. That has led some sophisticates to scorn them, but it has also attracted legions of admirers. One of them is Anne Wright, a Silicon Valley marketing executive who attended a Steinbeck memorial reception and dinner in San Jose, Calif.

''His style was like the people he wrote about,'' said Ms. Wright, who confided that according to family legend, she was delivered by the same doctor who delivered Steinbeck. ''It wasn't complex, or if it was, then not in a philosophical way.''

Several bookstores in the Salinas area are featuring Steinbeck's works or mounting special programs about him. At one store a collector and dealer, James Johnson, displayed posters from many of the more than 30 films that have been made from Steinbeck's works, along with copies of his books translated into languages including Farsi, Vietnamese and Slovenian.

''We don't know how many languages he's been translated into, but I have books in about 40 and I'd guess the total is around 60,'' Mr. Johnson said. ''He wrote about the common man, and in the end almost all of us think of ourselves as common. That transcends national boundaries.''

Japan is among the countries where Steinbeck's works are especially popular. A former executive director of the Steinbeck Society of Japan, Kiyoshi Nakayama, attended the Salinas festivities.

''We went through a very poor period after the war, and many people of that generation identified with what Steinbeck wrote,'' said Mr. Nakayama, whose 1998 translation of ''The Grapes of Wrath'' is the eighth to appear in Japanese. ''He is still very popular in Japan, even though there are more scholarly papers written about Hemingway and Faulkner.''

The debate over how Steinbeck compares with Hemingway and Faulkner, titans of his generation who also won the Nobel Prize, may be endless. Some critics have sought to dismiss him as less profound and more superficial than the other two, a straightforward storyteller beloved by high school students rather than a profound intellectual who probed the human psyche. Sometimes he is dismissed as unsophisticated, as when Edmund Wilson complained about ''the coarseness that tends to spoil Mr. Steinbeck as an artist.''

Susan Shillinglaw, a professor of English at San Jose State University and director of the Center for Steinbeck Studies, said she admired all three novelists and did not believe Steinbeck suffered by comparison.

''I love Hemingway's prose, and I think his short stories are some of the best in the language, but Steinbeck did the same kind of listening and simplifying,'' Ms. Shillinglaw said in an interview after addressing the crowd at Salinas. ''Steinbeck has more heart and soul, more empathy. He reaches out to readers with a participatory prose that invites us to engage, rather than writing as an observer the way Hemingway often does.

''Faulkner was certainly complex and experimental in a way that Steinbeck was not. He was more in touch with the modernism of people like Joyce and Virginia Woolf. But to compare him to Steinbeck is like comparing Picasso to Matisse. They weren't trying to do the same thing.''

Ms. Shillinglaw is the co-editor of a newly published anthology of Steinbeck's journalistic work, ''America and Americans,'' and also of a forthcoming book in which 23 American and foreign writers pay tribute to Steinbeck and assess his cultural influence. Contributors include Arthur Miller, Norman Mailer, E. L. Doctorow, Kurt Vonnegut and T. C. Boyle.

Among those who joined the celebration in Salinas was Thom Steinbeck, the author's only surviving child, who bears a striking resemblance to his father.

''He was an animist,'' Mr. Steinbeck said of his father while reminiscing between public appearances. ''He would tip his hat to dogs. He'd talk to screwdrivers, start a conversation with a parking meter at the drop of a hat.''

Mr. Steinbeck said that after years of monitoring the royalty checks the family receives for his father's works, he has developed a theory about the rises and falls in his popularity.

''Every time people are being driven out of work by powerful institutions that they think are against them, when there's unemployment and economic trouble, sales increase,'' Mr. Steinbeck said. ''When you have boom times like the mad 80's and there's plenty of money around, sales go down. It all depends on the age we're in.''

Searching for a story from Newsday ("He's part of our heritage", written by Aileen Jacobson, took me to the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies in the ML King Library at San Jose State University.

Found a Facebook page entitled Travels with Stenbeck; neat.

March 19, 2002

ARTS IN AMERICA; The Pride Of Salinas: Steinbeck At 100

By STEPHEN KINZER

SALINAS, Calif.— Here in the fertile California valley that was home to many of the hobos, vagrants, prostitutes and migrant farm laborers who populate the works of John Steinbeck, a yearlong celebration is under way to honor the writer's memory.

There are also events being planned elsewhere, including New York, where Steinbeck lived for the last 18 years of his life. There is a tribute at Lincoln Center tonight, a conference at Hofstra University from Thursday through Saturday and a film series in April and May at City University. A Web site, http://www.steinbeck100.org/ newevents.html, provides information on events in other areas.

The Steinbeck towns like Salinas are no longer ringed by shantytowns filled with hungry Dust Bowl refugees, as in ''The Grapes of Wrath.'' Down the road in Monterey, the immigrants and ne'er-do-wells who populate books like ''Cannery Row'' and ''Tortilla Flat'' have given way to boutique owners.

Yet since Steinbeck's death, in 1968, people here have become zealous guardians of his legacy, so the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas seemed the appropriate place for the cake-cutting that opened what is to be a year of speeches, public readings, concerts, academic conferences, film showings and other tributes.

Steinbeck's works are still widely read in the United States and abroad. Many of his admirers say that is because he conveys a love of the downtrodden, the exploited, the ones he called ''the gathered and the scattered.'' He spent years living among them and portrayed them as deftly as any American writer ever has.

The celebration in Salinas on Feb. 27, the 100th anniversary of Steinbeck's birth, included the reading of official proclamations and the presentation of prizes to local high school students who have studied Steinbeck. It was one of more than 175 tributes to be held this year in 39 states. Together they are said to make up the largest-scale homage ever paid to an American author.

Many of these events are being paid for by the National Endowment for the Humanities, which gave $260,000 to a coalition of 26 nonprofit cultural groups and 100 local libraries.

The California Council for the Humanities is planning an effort to persuade as many Californians as possible to read ''The Grapes of Wrath'' over the summer. Beginning in October, libraries and schools across the state will sponsor discussion groups and other events related to the book.

''The Grapes of Wrath,'' generally considered Steinbeck's masterpiece, grew out of a newspaper assignment to investigate the living conditions in California of migrants from the parched heartland. He wrote it during an intense six-month creative marathon in 1938, and its graphic portrayal of workers suffering at the hands of callous landowners brought him death threats, an F.B.I. investigation and charges of Communist sympathy.

That last charge may have seemed plausible during the contentious 1930's, when anyone speaking out for the rights of the poor was considered suspicious, but it sounds quite odd in light of Steinbeck's later opinions. After World War II he denounced Communists for having ''established the most reactionary governments in the world, governments so fearful of revolt that they must make every man an informer against his fellows, and layer their society with secret police.'' During the 1960's he was one of the few American intellectuals who refused to denounce the United States role in Vietnam.

Steinbeck won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1962. ''His sympathies always go out to the oppressed, the misfits and the distressed,'' the Nobel committee asserted in choosing him. ''He likes to contrast the simple joy of life with the brutal and cynical craving for money.''

In accepting the award, Steinbeck said: ''The ancient commission of the writer has not changed. He is charged with exposing our many grievous faults and failures, with dredging up to the light our dark and dangerous dreams for the purpose of improvement. Furthermore, the writer is delegated to declare and to celebrate man's proven capacity for greatness of heart and spirit -- for gallantry in defeat, for courage, compassion and love.''

During Steinbeck's childhood in Salinas, his parents often read aloud to him and his three sisters. He spent hours in the attic of his family home devouring books like ''Adventures of Huckleberry Finn'' and ''Ivanhoe'' and one that became a lifelong favorite, Malory's ''Morte d'Arthur.''

As he grew older, Steinbeck often left Salinas and traveled to the seaside town of Monterey, about 25 miles away. There he developed a bond with cannery workers, fishermen and others on the fringes of society.

Most of Steinbeck's works are straightforward, accessible and easy to read. That has led some sophisticates to scorn them, but it has also attracted legions of admirers. One of them is Anne Wright, a Silicon Valley marketing executive who attended a Steinbeck memorial reception and dinner in San Jose, Calif.

''His style was like the people he wrote about,'' said Ms. Wright, who confided that according to family legend, she was delivered by the same doctor who delivered Steinbeck. ''It wasn't complex, or if it was, then not in a philosophical way.''

Several bookstores in the Salinas area are featuring Steinbeck's works or mounting special programs about him. At one store a collector and dealer, James Johnson, displayed posters from many of the more than 30 films that have been made from Steinbeck's works, along with copies of his books translated into languages including Farsi, Vietnamese and Slovenian.

''We don't know how many languages he's been translated into, but I have books in about 40 and I'd guess the total is around 60,'' Mr. Johnson said. ''He wrote about the common man, and in the end almost all of us think of ourselves as common. That transcends national boundaries.''

Japan is among the countries where Steinbeck's works are especially popular. A former executive director of the Steinbeck Society of Japan, Kiyoshi Nakayama, attended the Salinas festivities.

''We went through a very poor period after the war, and many people of that generation identified with what Steinbeck wrote,'' said Mr. Nakayama, whose 1998 translation of ''The Grapes of Wrath'' is the eighth to appear in Japanese. ''He is still very popular in Japan, even though there are more scholarly papers written about Hemingway and Faulkner.''

The debate over how Steinbeck compares with Hemingway and Faulkner, titans of his generation who also won the Nobel Prize, may be endless. Some critics have sought to dismiss him as less profound and more superficial than the other two, a straightforward storyteller beloved by high school students rather than a profound intellectual who probed the human psyche. Sometimes he is dismissed as unsophisticated, as when Edmund Wilson complained about ''the coarseness that tends to spoil Mr. Steinbeck as an artist.''

Susan Shillinglaw, a professor of English at San Jose State University and director of the Center for Steinbeck Studies, said she admired all three novelists and did not believe Steinbeck suffered by comparison.

''I love Hemingway's prose, and I think his short stories are some of the best in the language, but Steinbeck did the same kind of listening and simplifying,'' Ms. Shillinglaw said in an interview after addressing the crowd at Salinas. ''Steinbeck has more heart and soul, more empathy. He reaches out to readers with a participatory prose that invites us to engage, rather than writing as an observer the way Hemingway often does.

''Faulkner was certainly complex and experimental in a way that Steinbeck was not. He was more in touch with the modernism of people like Joyce and Virginia Woolf. But to compare him to Steinbeck is like comparing Picasso to Matisse. They weren't trying to do the same thing.''

Ms. Shillinglaw is the co-editor of a newly published anthology of Steinbeck's journalistic work, ''America and Americans,'' and also of a forthcoming book in which 23 American and foreign writers pay tribute to Steinbeck and assess his cultural influence. Contributors include Arthur Miller, Norman Mailer, E. L. Doctorow, Kurt Vonnegut and T. C. Boyle.

Among those who joined the celebration in Salinas was Thom Steinbeck, the author's only surviving child, who bears a striking resemblance to his father.

''He was an animist,'' Mr. Steinbeck said of his father while reminiscing between public appearances. ''He would tip his hat to dogs. He'd talk to screwdrivers, start a conversation with a parking meter at the drop of a hat.''

Mr. Steinbeck said that after years of monitoring the royalty checks the family receives for his father's works, he has developed a theory about the rises and falls in his popularity.

''Every time people are being driven out of work by powerful institutions that they think are against them, when there's unemployment and economic trouble, sales increase,'' Mr. Steinbeck said. ''When you have boom times like the mad 80's and there's plenty of money around, sales go down. It all depends on the age we're in.''

Wednesday, December 10, 2008

Monday, August 26, 2002

another Writers on Writing

One more from my files, another Writers on Writing.

August 26, 2002

WRITERS ON WRITING; Why Not Put Off Till Tomorrow the Novel You Could Begin Today?

By Ann Patchett

My life is a series of ranked priorities. At the top of the list is the thing I do not wish to do the very most, and beneath that is everything else. There is vague order to the everything else, but it scarcely matters. The thing I really don't want to do is start my fifth novel, and the rest of my life is little more than a series of stalling techniques to help me achieve my goal.

This essay, for example, which I asked to write because all of the other essays I have thought of are now finished, will easily kill a day. I have already restored my oven to the level of showroom-floor cleanliness, written a small hill of thank-you notes (some of them completely indiscriminate: ''Thank you for sending me the list of typographical errors you found in my last novel''), walked the dog to the point of the dog's collapse. I've read most of the books I've been meaning to read since high school.

The sad part is, when there is something I very much don't want to do, I become incredibly fast about shooting through everything else. This week I have cleaned out my sister's closets. And then my mother's.

For a long time before I start to write a novel, anywhere from one year to two, I make it up. This is the happiest time I have with my books. The novel in my imagination travels with me like a small lavender moth making loopy circles around my head. It is a truly gorgeous thing, its unpredictable flight patterns, the amethyst light on its wings. I think of my characters as I wander through the grocery store. I write out their names like a teenage girl dreaming of marriage.

In these early pre-text days my story has more promise, more beauty, than I have ever seen in any novel ever written, because, sadly, this novel is not written. Then the time comes when I have to begin to translate ideas into words, a process akin to reaching into the air, grabbing my little friend (crushing its wings slightly in my thick hand), holding it down on a cork board and running it though with a pin. It is there that the lovely thing in my head dies.

I take some comfort that I've done this before, that eventually, perhaps even today, I will write the opening pages. Somewhere around Page 80 I will accept that I am neither smart enough nor talented enough to put all the light and movement and beauty I had hoped for onto paper, and so I will have to settle for what I am capable of pulling off. But the question then becomes: On what day do you do format a new file on the computer and type that first sentence? I don't actually sell the book until I've finished writing it, so I don't have a deadline to compel me. And if I'm careful with the money I've got, it could last me for a while.

Suddenly, five novels seems ungainly. The thought of it convinces me how boring I've become, and I start to wonder why I never went to medical school. I imagine Elizabeth Taylor choosing a dress in which to marry Richard Burton. Did she believe that this time everything would be different? That this time she would be true until death did them part? I marvel at such hopefulness.

Starting a novel isn't so different from starting a marriage. The dreams you pin on these people are enormous. You are diving into the lives of your characters, knowing that you will fall in love with all of them, knowing (as surely Elizabeth Taylor knew) that in the end the love will finish and turn you out on the street alone.

From the vantage point of a novelist trying to get inside the novel, it makes the most sense to me to shoot for something along the lines of ''A Man Without Qualities'' or ''Remembrance of Things Past,'' a genuine tome that will keep me busy for the next 30 years or so. But that doesn't work either, because as soon as I'm comfortably inside my book I inevitably long to get out. The farther into the story I get, the harder and faster I write. In short, I become a malcontent dog, either scratching to get in or scratching to get out.

It should be noted that there are two blissful things about writing novels: making them up and seeing them finished. The days I spend in either of these two states are so sweet, they easily make the rest of the process bearable. The novel in my head is all mapped out and ready to go, but in these final minutes before departure I feel the rocking waves of doubt.

In trying to start a novel, I dream about the novels I wish I had written, the ideas I should have had. A book about a boy in a boat with a Bengal tiger? Surely I would have come up with that one had Yann Martel not written ''Life of Pi.'' Surely with a little more time I would have come up with something as important and beautiful as Carol Shields's ''Unless.'' And yet, the books I most long to plagiarize are my own.

Every time I start a new novel, I think what a comfort it would be to crawl back into the broken-in softness of the old one. Would it be completely unreasonable to write another book about opera and South America? Would reviewers say I was in a rut? Honestly, how often do reviewers actually read the preceding novels? Of course when I was starting ''Bel Canto,'' I was longing for just one more book about a gay magician, and so on, backward.

Despite the hand wringing, housekeeping and the overdrive of unnecessary productivity, there will come a point very soon when I will begin, if for no other reason than the stress of not beginning will finally overwhelm me. That, and I'll want to see how the whole thing ends. Sometimes if there's a book you really want to read, you have to write it yourself.

Writers on Writing

Articles in this series are presenting writers' exploration of literary themes. Previous contributions are online: nytimes.com/books/columns

August 26, 2002

WRITERS ON WRITING; Why Not Put Off Till Tomorrow the Novel You Could Begin Today?

By Ann Patchett

My life is a series of ranked priorities. At the top of the list is the thing I do not wish to do the very most, and beneath that is everything else. There is vague order to the everything else, but it scarcely matters. The thing I really don't want to do is start my fifth novel, and the rest of my life is little more than a series of stalling techniques to help me achieve my goal.

This essay, for example, which I asked to write because all of the other essays I have thought of are now finished, will easily kill a day. I have already restored my oven to the level of showroom-floor cleanliness, written a small hill of thank-you notes (some of them completely indiscriminate: ''Thank you for sending me the list of typographical errors you found in my last novel''), walked the dog to the point of the dog's collapse. I've read most of the books I've been meaning to read since high school.

The sad part is, when there is something I very much don't want to do, I become incredibly fast about shooting through everything else. This week I have cleaned out my sister's closets. And then my mother's.

For a long time before I start to write a novel, anywhere from one year to two, I make it up. This is the happiest time I have with my books. The novel in my imagination travels with me like a small lavender moth making loopy circles around my head. It is a truly gorgeous thing, its unpredictable flight patterns, the amethyst light on its wings. I think of my characters as I wander through the grocery store. I write out their names like a teenage girl dreaming of marriage.

In these early pre-text days my story has more promise, more beauty, than I have ever seen in any novel ever written, because, sadly, this novel is not written. Then the time comes when I have to begin to translate ideas into words, a process akin to reaching into the air, grabbing my little friend (crushing its wings slightly in my thick hand), holding it down on a cork board and running it though with a pin. It is there that the lovely thing in my head dies.

I take some comfort that I've done this before, that eventually, perhaps even today, I will write the opening pages. Somewhere around Page 80 I will accept that I am neither smart enough nor talented enough to put all the light and movement and beauty I had hoped for onto paper, and so I will have to settle for what I am capable of pulling off. But the question then becomes: On what day do you do format a new file on the computer and type that first sentence? I don't actually sell the book until I've finished writing it, so I don't have a deadline to compel me. And if I'm careful with the money I've got, it could last me for a while.

Suddenly, five novels seems ungainly. The thought of it convinces me how boring I've become, and I start to wonder why I never went to medical school. I imagine Elizabeth Taylor choosing a dress in which to marry Richard Burton. Did she believe that this time everything would be different? That this time she would be true until death did them part? I marvel at such hopefulness.

Starting a novel isn't so different from starting a marriage. The dreams you pin on these people are enormous. You are diving into the lives of your characters, knowing that you will fall in love with all of them, knowing (as surely Elizabeth Taylor knew) that in the end the love will finish and turn you out on the street alone.

From the vantage point of a novelist trying to get inside the novel, it makes the most sense to me to shoot for something along the lines of ''A Man Without Qualities'' or ''Remembrance of Things Past,'' a genuine tome that will keep me busy for the next 30 years or so. But that doesn't work either, because as soon as I'm comfortably inside my book I inevitably long to get out. The farther into the story I get, the harder and faster I write. In short, I become a malcontent dog, either scratching to get in or scratching to get out.

It should be noted that there are two blissful things about writing novels: making them up and seeing them finished. The days I spend in either of these two states are so sweet, they easily make the rest of the process bearable. The novel in my head is all mapped out and ready to go, but in these final minutes before departure I feel the rocking waves of doubt.

In trying to start a novel, I dream about the novels I wish I had written, the ideas I should have had. A book about a boy in a boat with a Bengal tiger? Surely I would have come up with that one had Yann Martel not written ''Life of Pi.'' Surely with a little more time I would have come up with something as important and beautiful as Carol Shields's ''Unless.'' And yet, the books I most long to plagiarize are my own.

Every time I start a new novel, I think what a comfort it would be to crawl back into the broken-in softness of the old one. Would it be completely unreasonable to write another book about opera and South America? Would reviewers say I was in a rut? Honestly, how often do reviewers actually read the preceding novels? Of course when I was starting ''Bel Canto,'' I was longing for just one more book about a gay magician, and so on, backward.

Despite the hand wringing, housekeeping and the overdrive of unnecessary productivity, there will come a point very soon when I will begin, if for no other reason than the stress of not beginning will finally overwhelm me. That, and I'll want to see how the whole thing ends. Sometimes if there's a book you really want to read, you have to write it yourself.

Writers on Writing

Articles in this series are presenting writers' exploration of literary themes. Previous contributions are online: nytimes.com/books/columns

Monday, June 17, 2002

Recognizing The Book

June 17, 2002

WRITERS ON WRITING; Recognizing The Book That Needs To Be Written

By DOROTHY GALLAGHER

Years ago, I picked up a copy of Sarah Orne Jewett's collection of stories ''The Country of the Pointed Firs.'' These are wonderful stories. But what struck me at the time, and what has stayed with me, is a letter from Jewett to Willa Cather that Cather quotes in her preface to the book:

''The thing that teases the mind over and over for years, and at last gets itself put down rightly on paper -- whether little or great, it belongs to Literature.''

The thing that teases the mind. . . . A writer is always preoccupied with identifying the material that is essential to her work, the book that needs to be written. If there is such a core of material, bits and pieces of it will find their way into everything she writes, even into an editor's assignment. And she waits for that moment of synthesis when the subject finds the vehicle for its expression.

For me, that moment first came in the late 1970's. I learned then about an obscure Italian-American anarchist named Carlo Tresca. By that time Tresca had been dead for more than 30 years, murdered in 1943. I had never heard of him, but I recognized him at once. He was the embodiment of my subject. In writing his life, I would at last be dealing with the material that was necessary to me.

And to say what that is, I will turn to another writer, Robert Warshow, who died young, in the 1950's, still in his 30's, but who produced in his short life a number of brilliant essays on American cultural life that are collected as ''The Immediate Experience.'' In one essay Warshow wrote about the crucial effect of the American Communist movement on the intellectual life of the country in the 1930's.

There was a time, Warshow wrote, when virtually all intellectual vitality was derived in one way or another from the Communist Party. ''If you were not somewhere within the party's wide orbit'' -- and he was referring to the days of the Popular Front, the Spanish Civil War, the rise of Fascism: the time of the party's greatest influence in America and in Europe -- ''then you were likely to be in the opposition, which meant that much of your thought and energy had to be devoted to maintaining yourself in opposition. In either case, it was the Communist Party that determined what you were to think about and in what terms.''

The world has moved on, and very quickly, too. Fanatical ideologies have taken different forms, and even as we watch at this moment, we see the categories of political and social thought that defined the world through the 1980's dissolve and re-form in strange and terrifying ways. But it was the idiom of the Communist Party that I took in with my mother's milk: it was my introduction to intellectual experience and to the dense web of loyalties and enmities that ideology so dangerously generates; and it continues to engage me as nothing else does.

And, really, why wouldn't it? Unquestioning belief in an abstract idea is a peculiar feature of our species that transcends the ages. The historian Martin Malia called Communism ''the great political religion of the modern age . . . promising egalitarian redemption at the end of history.'' Worse, almost, than the horrific acts committed in its name, Communist ideology appropriated the language of the best hopes and ideals of humanity. And every horror was called by the name of its opposite, as George Orwell noticed.

Many immigrant Jews, as my own family did, lived in fairly isolated enclaves, among people who had come from the same part of the world -- Eastern Europe, Russia -- and who largely shared their views. It was possible for that immigrant generation to live an entire life in America with little connection to the people and country of their emigration.

If my grandfather kept the God of the shtetl, my mother's generation found life's meaning in the Bolshevik revolution. It was left to their children, who were the first generation born in America, to connect with the new world. And for many years that was my business: finding a foothold on this ground. When I felt firmly grounded, the past asserted itself, and I eventually found Carlo Tresca, an anarchist, whose political viewpoint had led him very early to see the dangers of Bolshevism. He became my vehicle and guide to what had always been waiting at the back of my mind.

Writing is problem solving; whether in fiction, biography or memoir, certain basic questions have to be resolved. In biography, at least, a writer leans heavily on materials gathered in research. Working with a trove of documents is constraining, but also in some ways liberating, as working a puzzle is liberating. The clues are in your files, and if you've done your job as a researcher, you have the tools to solve the puzzle. But when I turned to memoir -- the shamelessly naked core of a writer's necessary material -- I found myself traveling as light as any writer of fiction.

I have never written fiction, and this memoir may be as close as I ever get to it. No more than a biography or a novel is memoir true to life. Because, truly, life is just one damn thing after another. The writer's business is to find the shape in unruly life and to serve her story. Not, you may note, to serve her family, or to serve the truth, but to serve the story. There really is no choice. A reporter of fact is in service to the facts, a eulogist to the family of the dead, but a writer serves the story without apology to competing claims.

This is an attitude that some have characterized as ruthless: that cold detachment, that remove, that allows writers to make a commodity of the lives of others. But a writer who cannot separate herself from her characters and see them within the full spectrum of their human qualities loses everything in a haze of nostalgia and sentimentality. Bathos would do no honor to my subjects nor, most important, bring them to literary life, which is the only way they could live in the world again.

At first I intended to write only one piece, the story of the agonizing last years of my parents' lives, a five-year period during which I had made some notes. The original version of the story I wrote was about 150 pages long. Everything was in it, but it didn't work. I hadn't solved any of the problems that the story demanded. But I was lucky, and eventually a solution came to me.

The right voice in which to tell the story came to me, and when it did, many other things fell into place. And I wound up with a story that is 10 or 12 pages long and yet contains everything I wanted to say. After that first piece, I went on to make a book of stories about my family that I called ''How I Came Into My Inheritance and Other True Stories,'' without notes this time, with only treacherous memory and a few letters to guide me.

Now you may ask: Just what is the relation of your memoir to the truth?

It is as close as it can be.

The moment you put pen to paper and begin to shape a story, the essential nature of life -- that one damn thing after another -- is lost. No matter how ambiguous you try to make a story, no matter how many ends you leave hanging, it's a package made to travel.

Everything that happened is not in my stories; how could it be? Memory is selective, storytelling insists on itself. But there is nothing in my stories that did not happen. In their essence they are true.

Or a shade of true. There is a piece in my memoir that I call ''Cousin Meyer's Autobiography.'' I did not really write this story. My cousin, whose real name was Oscar, left a self-printed memoir of some hundred pages. The first liberty I took with it was to change his name to Meyer in order to avoid confusion with my uncle whose name was Oscar.

Cousin Meyer's memoir was a treasure; it told of some extraordinary events in his life that dovetailed with the central material of my book. I took his hundred pages, reduced them in the way you would reduce a sauce, I turned them a little, say fron north to northeast. The result may not be the story he wanted people to read. I took his story over, I insisted on my interpretation, I even added some lines that he did not write.

Did I have a right to do that? Some would say not, and really I would have no defense. Nevertheless, if cousin Meyer, so incensed by my interference, returned from the dead to object, I would answer him: But, cousin, for more than 20 years your story languished in a drawer; you were dead in fact, your life lingered in hardly anyone's memory. And now, because I have used you, more people have read your story than you ever could have dreamed. Cousin, you live, even if you dance to my tune.

Writers on Writing

Articles in this series are presenting writers' exploration of literary themes. Previous contributions: nytimes.com/books/columns

WRITERS ON WRITING; Recognizing The Book That Needs To Be Written

By DOROTHY GALLAGHER

Years ago, I picked up a copy of Sarah Orne Jewett's collection of stories ''The Country of the Pointed Firs.'' These are wonderful stories. But what struck me at the time, and what has stayed with me, is a letter from Jewett to Willa Cather that Cather quotes in her preface to the book:

''The thing that teases the mind over and over for years, and at last gets itself put down rightly on paper -- whether little or great, it belongs to Literature.''

The thing that teases the mind. . . . A writer is always preoccupied with identifying the material that is essential to her work, the book that needs to be written. If there is such a core of material, bits and pieces of it will find their way into everything she writes, even into an editor's assignment. And she waits for that moment of synthesis when the subject finds the vehicle for its expression.

For me, that moment first came in the late 1970's. I learned then about an obscure Italian-American anarchist named Carlo Tresca. By that time Tresca had been dead for more than 30 years, murdered in 1943. I had never heard of him, but I recognized him at once. He was the embodiment of my subject. In writing his life, I would at last be dealing with the material that was necessary to me.

And to say what that is, I will turn to another writer, Robert Warshow, who died young, in the 1950's, still in his 30's, but who produced in his short life a number of brilliant essays on American cultural life that are collected as ''The Immediate Experience.'' In one essay Warshow wrote about the crucial effect of the American Communist movement on the intellectual life of the country in the 1930's.

There was a time, Warshow wrote, when virtually all intellectual vitality was derived in one way or another from the Communist Party. ''If you were not somewhere within the party's wide orbit'' -- and he was referring to the days of the Popular Front, the Spanish Civil War, the rise of Fascism: the time of the party's greatest influence in America and in Europe -- ''then you were likely to be in the opposition, which meant that much of your thought and energy had to be devoted to maintaining yourself in opposition. In either case, it was the Communist Party that determined what you were to think about and in what terms.''

The world has moved on, and very quickly, too. Fanatical ideologies have taken different forms, and even as we watch at this moment, we see the categories of political and social thought that defined the world through the 1980's dissolve and re-form in strange and terrifying ways. But it was the idiom of the Communist Party that I took in with my mother's milk: it was my introduction to intellectual experience and to the dense web of loyalties and enmities that ideology so dangerously generates; and it continues to engage me as nothing else does.

And, really, why wouldn't it? Unquestioning belief in an abstract idea is a peculiar feature of our species that transcends the ages. The historian Martin Malia called Communism ''the great political religion of the modern age . . . promising egalitarian redemption at the end of history.'' Worse, almost, than the horrific acts committed in its name, Communist ideology appropriated the language of the best hopes and ideals of humanity. And every horror was called by the name of its opposite, as George Orwell noticed.

Many immigrant Jews, as my own family did, lived in fairly isolated enclaves, among people who had come from the same part of the world -- Eastern Europe, Russia -- and who largely shared their views. It was possible for that immigrant generation to live an entire life in America with little connection to the people and country of their emigration.

If my grandfather kept the God of the shtetl, my mother's generation found life's meaning in the Bolshevik revolution. It was left to their children, who were the first generation born in America, to connect with the new world. And for many years that was my business: finding a foothold on this ground. When I felt firmly grounded, the past asserted itself, and I eventually found Carlo Tresca, an anarchist, whose political viewpoint had led him very early to see the dangers of Bolshevism. He became my vehicle and guide to what had always been waiting at the back of my mind.

Writing is problem solving; whether in fiction, biography or memoir, certain basic questions have to be resolved. In biography, at least, a writer leans heavily on materials gathered in research. Working with a trove of documents is constraining, but also in some ways liberating, as working a puzzle is liberating. The clues are in your files, and if you've done your job as a researcher, you have the tools to solve the puzzle. But when I turned to memoir -- the shamelessly naked core of a writer's necessary material -- I found myself traveling as light as any writer of fiction.

I have never written fiction, and this memoir may be as close as I ever get to it. No more than a biography or a novel is memoir true to life. Because, truly, life is just one damn thing after another. The writer's business is to find the shape in unruly life and to serve her story. Not, you may note, to serve her family, or to serve the truth, but to serve the story. There really is no choice. A reporter of fact is in service to the facts, a eulogist to the family of the dead, but a writer serves the story without apology to competing claims.

This is an attitude that some have characterized as ruthless: that cold detachment, that remove, that allows writers to make a commodity of the lives of others. But a writer who cannot separate herself from her characters and see them within the full spectrum of their human qualities loses everything in a haze of nostalgia and sentimentality. Bathos would do no honor to my subjects nor, most important, bring them to literary life, which is the only way they could live in the world again.

At first I intended to write only one piece, the story of the agonizing last years of my parents' lives, a five-year period during which I had made some notes. The original version of the story I wrote was about 150 pages long. Everything was in it, but it didn't work. I hadn't solved any of the problems that the story demanded. But I was lucky, and eventually a solution came to me.

The right voice in which to tell the story came to me, and when it did, many other things fell into place. And I wound up with a story that is 10 or 12 pages long and yet contains everything I wanted to say. After that first piece, I went on to make a book of stories about my family that I called ''How I Came Into My Inheritance and Other True Stories,'' without notes this time, with only treacherous memory and a few letters to guide me.

Now you may ask: Just what is the relation of your memoir to the truth?

It is as close as it can be.

The moment you put pen to paper and begin to shape a story, the essential nature of life -- that one damn thing after another -- is lost. No matter how ambiguous you try to make a story, no matter how many ends you leave hanging, it's a package made to travel.

Everything that happened is not in my stories; how could it be? Memory is selective, storytelling insists on itself. But there is nothing in my stories that did not happen. In their essence they are true.

Or a shade of true. There is a piece in my memoir that I call ''Cousin Meyer's Autobiography.'' I did not really write this story. My cousin, whose real name was Oscar, left a self-printed memoir of some hundred pages. The first liberty I took with it was to change his name to Meyer in order to avoid confusion with my uncle whose name was Oscar.

Cousin Meyer's memoir was a treasure; it told of some extraordinary events in his life that dovetailed with the central material of my book. I took his hundred pages, reduced them in the way you would reduce a sauce, I turned them a little, say fron north to northeast. The result may not be the story he wanted people to read. I took his story over, I insisted on my interpretation, I even added some lines that he did not write.

Did I have a right to do that? Some would say not, and really I would have no defense. Nevertheless, if cousin Meyer, so incensed by my interference, returned from the dead to object, I would answer him: But, cousin, for more than 20 years your story languished in a drawer; you were dead in fact, your life lingered in hardly anyone's memory. And now, because I have used you, more people have read your story than you ever could have dreamed. Cousin, you live, even if you dance to my tune.

Writers on Writing

Articles in this series are presenting writers' exploration of literary themes. Previous contributions: nytimes.com/books/columns

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)