1. Scarlett O'Hara's Younger Sister

By Evelyn Keyes

Stuart, 1977

As the title of Evelyn Keyes's exuberantly clear-eyed autobiography makes clear, the woman who played Suellen in "Gone With the Wind" was more often bridesmaid than star. But what she was denied on the screen she made up for on the page in one of the juiciest and most shrewdly observed books ever to come out of Hollywood. The actress who grew up poor and provincial in Atlanta went knocking on studio doors with nothing more than a vague dream of stardom and a naïveté so thick it was almost a protective armor. She needed every bit of that, and her extraordinary humor, to survive the Daddy figures who served as mentors and something more: Cecil B. DeMille, Harry Cohn, Charles Vidor and John Huston, her third and most flamboyant husband. He takes her out deer hunting in Idaho and fishing with Hemingway in Key West (where the writer's wife, Maria, "cleaned her toenails with a long knife and cut the bread with it afterward"). On the Idaho trip, under Huston's tutelage, Keyes successfully kills a buck -- an experience that her husband later describes as "the best part of our life together." In "Scarlett O'Hara's Younger Sister," Keyes, who died last summer, raises unflappability to a fine art. Don't be fooled by the throwaway style: The timing is too good, the mots too justes.

2. The Lonely Life

By Bette Davis

Putnam, 1962

Any actress who can expose herself to the flesh-peddling standards of Hollywood -- surviving such confidence-shattering epithets as "little brown wren" and "as sexy as Slim Summerville" -- and still insist on a high-toned career while staring down studio bosses has chutzpah to burn. And Bette Davis, a stalwart New Englander who made three movies a year while using her excess energy to fight with Warner Bros., had it in spades. Even more important than sheer ambition, or perhaps it is one of ambition's hallmarks, was Davis's ability to put aside her East Coast theatrical snobbery and see movies as a different medium and moviemaking as a craft with different technical demands that she was determined to learn. As suggested by the title of her memoir, "The Lonely Life," Davis had little interest in false pride; she describes the highs and lows of her career and marriages, coming to the realization that you can't "have it all." Her attempts to be a "real" wife were doomed to failure, she confesses. The role of the "little woman" was perhaps the only one totally beyond her.

3. My Story

By Mary Astor

Doubleday, 1959

Though she made more than a hundred films, most of them silents, the dark-eyed beauty Mary Astor was never a mega-star, but she was more interesting than many who were. Astor was the daughter of an educated, schoolteacher mother and an ambitious German immigrant father so grasping and domineering that studio executives refused to negotiate with him. Sheltered and exploited her entire life, she hadn't had a chance to develop a moral compass or a sense of self before falling under the spell of mentor-lovers both kind (Jack Barrymore) and ambivalent (the rest), and of husbands (four in all) with a lower libido than hers. An increasingly disabling alcoholism led her first to the Catholic Church and then (with the encouragement of a priest-psychotherapist) to the writing of this remarkable book, in which she comes to terms with the rushed-into marriages, the drinking and above all the furor in the 1930s over a diary -- which surfaced during a child-custody battle with one of her ex-husbands -- in which she recorded her affair with writer George S. Kaufman. In "My Story," Astor displays those unusual and very grown-up qualities -- refined but sensual, stand-offish but come-hither -- that sometimes were a liability in Hollywood casting but make for a complex and riveting memoir.

4. Lulu in Hollywood

By Louise Brooks

Knopf, 1982

After laboring for much of the 1920s in Hollywood, the black-helmeted Kansas-born free spirit Louise Brooks had to go to Europe to become a star. She was a revelation in two mesmerizing German silent films directed by G.W. Pabst, "Pandora's Box" (1928) and "Diary of a Lost Girl" (1929) -- but then Brooks, independent-minded to a fault, refused to compromise once Hollywood came calling, and she basically threw her career away. By the late 1940s, she was working as a saleslady at Saks Fifth Avenue in New York. She was rescued by admirers, chief among them James Card, curator of the George Eastman House film archive in Rochester, N.Y. He persuaded Brooks to move to Rochester, where she lived in the 1950s as a recluse, watched films, her own and others, and was reborn as a writer. (She was also rediscovered as an actress by Kenneth Tynan, who championed her work in an influential piece for The New Yorker.) "Lulu in Hollywood" -- Lulu was the ill-fated innocent who drove men to distraction in "Pandora's Box" -- is a collection of Brooks's often brilliant essays. Some of the pieces recount her own joyous romp through the 1920s as a Ziegfeld showgirl (a job she enjoyed more than making movies) and party-girl courtesan. Other essays shimmer with insight as she discusses the work of Humphrey Bogart, W.C. Fields, Greta Garbo, Lillian Gish and others. She paints a vivid picture of Bogie, for instance, still showing vestiges of the stiff stage actor in "The Roaring Twenties" in 1939, when he appears helpless opposite James Cagney, whose "swift dialogue" and "swift movements . . . had the glitter and precision of a meat slicer . . . impossible to anticipate or counterattack."

5. Me

By Katharine Hepburn

Random House, 1991

Katharine Hepburn, equal to Bette Davis in ambition, seems in this memoir also to share her sense of solitary pursuit: "People who want to be famous are really loners. Or they should be." Like Davis, Hepburn put career first; unlike Davis, she never really fantasized the perfect marriage and the little white house. Until she fell for Spencer Tracy, she kept her lovers -- Howard Hughes, Leland Hayward -- at arm's length and was a shrewd businesswoman from the start. Her writing style consists of a slapdash series of jottings to self and fans, as if she were dictating while striding over a golf course. Yet "Me" captures beautifully that signal Hepburn combination of presumption and insecurity, self-love and abject humility. Should I have done this, done that? Wasn't I a bitch! And, yes, she was, often, but also an enchantress, and she is unstinting in showing us both. A superhuman resiliency allows her (like Davis) to suffer the most humiliating setbacks -- she was once famously declared "box-office poison" -- and continue going forward. Her flinty New England upbringing was both inspiration and protection: At her parents' urging, she was diving off cliffs, wrestling and competing from an early age, turning fear into something she feared so much that it made her fearless.

Ms. Haskell's "Frankly My Dear: Gone With the Wind Revisited" will be published next week by Yale University Press.

* FIVE BEST

* FEBRUARY 21, 2009

Printed in The Wall Street Journal, page W8

The Lost City of Z

The Lost City of Z

Another excellent film. This review captures it well.

Another excellent film. This review captures it well. The attention is deserved – after a lifetime of supporting roles, Jenkins finally gets his chance to truly shine in The Visitor, and he knocks it out of the park, using all of the film’s 104 minutes to peel away his character’s layers with a quiet performance that’s almost Newmanesque in its finely shaded understatement. Jenkins plays Connecticut college professor Walter Vale, who begins the picture as a bit of a douche – in the opening scenes, he fires his piano teacher and curtly dismisses a student’s pleas for mercy – and such a wet noodle that by the time he’s strong-armed into traveling to New York to present a paper he co-authored in name only, you may be wondering how and why he deserves his own movie.

The attention is deserved – after a lifetime of supporting roles, Jenkins finally gets his chance to truly shine in The Visitor, and he knocks it out of the park, using all of the film’s 104 minutes to peel away his character’s layers with a quiet performance that’s almost Newmanesque in its finely shaded understatement. Jenkins plays Connecticut college professor Walter Vale, who begins the picture as a bit of a douche – in the opening scenes, he fires his piano teacher and curtly dismisses a student’s pleas for mercy – and such a wet noodle that by the time he’s strong-armed into traveling to New York to present a paper he co-authored in name only, you may be wondering how and why he deserves his own movie. Of course, chance encounters can be good or bad – something McCarthy reminds us in The Visitor’s second act, when Walter is called upon to help Tarek out of a sudden, terrible predicament. The ways he answers this call, and the completion of his transformation from closed circuit to human conduit, are best left out of this review; suffice it to say The Visitor is a beautifully tender drama built out of small, warm moments, with some profound things to say about the possibilities buried in every stranger you pass on the street. It’s sort of the anti-Death Wish, offering a glimpse of city life that’s rife with hope and brotherhood. Jenkins has said he’s waited his entire professional career to be a part of something like The Visitor, and after watching the film, you’ll be as glad as he is that the opportunity presented itself.

Of course, chance encounters can be good or bad – something McCarthy reminds us in The Visitor’s second act, when Walter is called upon to help Tarek out of a sudden, terrible predicament. The ways he answers this call, and the completion of his transformation from closed circuit to human conduit, are best left out of this review; suffice it to say The Visitor is a beautifully tender drama built out of small, warm moments, with some profound things to say about the possibilities buried in every stranger you pass on the street. It’s sort of the anti-Death Wish, offering a glimpse of city life that’s rife with hope and brotherhood. Jenkins has said he’s waited his entire professional career to be a part of something like The Visitor, and after watching the film, you’ll be as glad as he is that the opportunity presented itself.

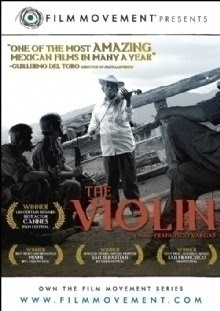

The violin

The violin

Master of War: The Life of General George H. Thomas.

Master of War: The Life of General George H. Thomas. The Painter’s Chair: George Washington and the Making of American Art.

The Painter’s Chair: George Washington and the Making of American Art. The Rebellion of Ronald Reagan: A History of the End of the Cold War.Mann, James (author).

The Rebellion of Ronald Reagan: A History of the End of the Cold War.Mann, James (author). Mecca and Main Street : Muslim life in America after 9/11./ Geneive Abdo.

Mecca and Main Street : Muslim life in America after 9/11./ Geneive Abdo.

Read the first few pages, recommended a patron; great writing, great use of language.

Read the first few pages, recommended a patron; great writing, great use of language.

Recommended by a patron.

Recommended by a patron.