On a Cole Porter kick.

Realistic, in a contemporary sense. Who knows what really went on? Porter was bisexual, and that is shown in this film. The music is great. Performances by Diana Krall, Elvis Costello and Robbie Williams sizzle. Kevin Kline and Ashley Judd do wonderful acting.

I did not like Cary Grant very much, and, after this film, by opinion has not changed. The film is mediocre, at best.

Tuesday, December 29, 2009

Wednesday, December 23, 2009

Swing time

Saw a biography of director George Stevens on Turner Classic Movies, including clips from several of his films. I was surprised, when I searched the OPAC, that this was one of his films.

Saw a biography of director George Stevens on Turner Classic Movies, including clips from several of his films. I was surprised, when I searched the OPAC, that this was one of his films.Ginger Rogers was flawless, Fred Astaire wonderful, and the movie worked pretty nicely. Victor Moore played Pop, and Helen Broderick played Mabel (trivia: she was mother of Broderick Crawford).

Nice dancing, good music.

Monday, December 21, 2009

Gran Torino

Excellent. Eastwood plays a gruff retired auto worker who has just buried his wife. Cantankerous, he is aggravated by everything. Hmong have moved next door. Walt lives in the past, his Korean War service informing and haunting his every day. A chance encounter with his neighbors leads to friendships, loyalty, and sacrifice.

Excellent. Eastwood plays a gruff retired auto worker who has just buried his wife. Cantankerous, he is aggravated by everything. Hmong have moved next door. Walt lives in the past, his Korean War service informing and haunting his every day. A chance encounter with his neighbors leads to friendships, loyalty, and sacrifice.Funny, poignant, exceedingly well acted, directed and photographed, this is American film making at its best.

Sunday, November 29, 2009

Umbria

Again, for the umteenth time.

Again, for the umteenth time."I may be dead next month. The moon may have crashed into the earth. Who knows what dreadful things might have come to pass. But, at the moment, I'm happy. What else matters?"

"Carpe diem."

"You know, I'm never really sure what that means."

"Seize the day; embrace the present; enjoy life, while you've got the chance."

"Carpe diem. I'll remember that."

Try: http://thecia.com.au/reviews/m/my-house-in-umbria.shtml

Wednesday, November 25, 2009

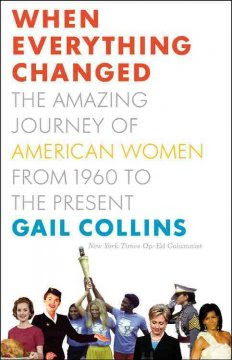

American women

Quite favorably discussed in the 17 December 2009 issue of the New York Review of Books by Cathleen Schine

Quite favorably discussed in the 17 December 2009 issue of the New York Review of Books by Cathleen Schine

Labels:

American history,

Book,

Book review,

Books,

Women

Friday, November 20, 2009

A Nasty Way With Words

Poisoned Pens. Edited by Gary Dexter. 2009.

Poisoned Pens. Edited by Gary Dexter. 2009.Portly G.K. Chesterton once remarked to the exiguous George Bernard Shaw: "To look at you, anyone would think there was a famine in England." To which Shaw replied: "To look at you, anyone would think you caused it."

A monstrous snob, Vladimir Nabokov criticized Fyodor Dostoevsky for his "lack of taste." H. Rider Haggard, the author of "King Solomon's Mines," denounced Anthony Trollope (whom he met in South Africa) for being "obstinate as a pig" and filled with "peculiar ideas."

For sheer schadenfreude "Poisoned Pens" is a book that one can pick up and put down anywhere. There are some notable gaps in the collection. We see nothing of H.L. Mencken. (The focus is mainly British.) Neither is mention made of Baron Corvo, one of literature's most contumacious practitioners, a man who lived to dish and to vilify. Nor are we are treated to anything from the late Truman Capote—"That's not writing," so went his famous remark on Jack Kerouac, "that's typing"—who could have taken up a whole chapter by himself.

The nastiness is amazing. Do buy copies of "Poisoned Pens" for your curmudgeonly friends. It is a perfect Christmas book for those seeking to stem the glut of good will.

Labels:

Books,

Insults,

Nastiness,

Schadenfreude,

Writers

Thursday, November 12, 2009

Sleuth

Usually I do not like to compare films, but let each stand on its own merits, but, I do feel compelled to say, this original version is superior to the 2007 version.

Usually I do not like to compare films, but let each stand on its own merits, but, I do feel compelled to say, this original version is superior to the 2007 version.I liked the 2007 film, with Michale Kane playing Andrew Wyke, the role Laurence Olivier played in the 1972 film; Caine played Milo Tindle in 1972. Jude Law played Mile Tindle in the 2007 version. All the acting is quite good; Olivier was superb, Caine better in 1972 than in 2007, and Law was excellent.

New books

Witold Gombrowicz,

New book: Pornografia (He died in 1969)

Thucydides : the reinvention of history

New book: Pornografia (He died in 1969)

There Is No Freedom Without Bread!: 1989 and the Civil War That Brought Down ...

Constantine Pleshakov - History - 2009 - 304 pages - No preview availableThucydides : the reinvention of history

Sunday, November 8, 2009

Books That Evoke Time and Place

November 7, 2009 - Penelope Lively says these books excel in depicting a particular time and place

1. The Boys' Crusade. By Paul Fussell. Modern Library, 2003 940.5421 F

In 1944, during the run-up to D-Day, two million young American men were given 17 weeks of basic training and shipped to Europe. Over the course of 11 months, from the Normandy landings to Germany's surrender, 135,000 U.S. infantrymen were killed and half a million wounded. Paul Fussell was among the soldiers who came home. He offers a brief, selective and forceful account of that period in "The Boys' Crusade"— and boys is what they largely were. The jacket of my copy shows the face of what one can only see as a child, swamped by his helmet. The book makes liberal use of eye-witness quotation—one soldier describes finding German corpses, "gray teeth, gray hands, worn boots, no identities . . . dead meat, nothing to grieve," and being "stupefied by the death we'd breathed"—an effect that plunges the reader into specific actions and the day-by-day routines of combat. But "The Boys' Crusade" also evokes the outlook of those teenagers—their blithe fidelity to the idea of America as the best and only modern country in the world, and their rapid exposure to the grim realities of an annihilating war.

2. The Last September. By Elizabeth Bowen. The Dial Press, 1929. FIC Bowen

This early novel by Elizabeth Bowen (1899-1973) is set in September 1920, at one of the "great houses" of the Anglo-Irish landowning Protestant families in southern Ireland. The central figure is Lois, a teenager staying on the estate, called Danielstown, with her aunt and uncle. There are tennis parties and dances—Lois loves a British officer from the nearby army station. But behind the story of this happy, innocent girl lurks another one: Ireland is in the midst of violent turmoil—guerrilla conflict between Irish rebels and the British troops who garrison the land. There are ambushes, reprisals, figures glimpsed in the darkness, rumors of arms caches. None of this is made explicit; instead, it surfaces in hints and clues that disturb the autumn program of social events. Until, at the end, there is the stark account of what came soon after: "A fearful scarlet ate up the hard spring darkness."

3. A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare. By James Shapiro. HarperCollins, 2005 822.33 Shakespeare S

James Shapiro places Shakespeare and his plays in their historical context, demonstrating how a yearlong burst of creative activity in 1599—"Henry V," "Julius Caesar," "As You Like It," the first draft of "Hamlet"—was prompted and fueled by what was actually happening at the time. England was threatened by Spain and its armada (possibly inspiring the "jittery soldiers" early in "Hamlet"), for instance, and Queen Elizabeth's favorite, the Earl of Essex, was pursuing a disastrous campaign to put down an Irish insurrection ("Henry V" mentions a general "from Ireland coming, / Bring rebellion broached on his sword"). The aging Elizabeth, with no successor waiting, feared assassination; "Julius Caesar" depicted the murder of a ruler. By finding public concerns reflected in the plays that Shakespeare was writing, Shapiro cunningly carries readers back to a single year and shows an extraordinary mind at work.

4. The Common Stream. By Rowland Parker. Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1975. 942.0657 P

Rowland Parker's publication of "The Common Stream" more than three decades ago was a pioneering instance of what is now known as micro-history. Parker was not a professional historian; he lived in the village of Foxton in eastern England and became fascinated by the visible presence of the past all around him. He walked, dug, ferreted in archives and eventually produced this remarkable reconstruction of how people had lived in one small part of the world for 2,000 years. The presence of water determined the beginnings of settlement, hence "the common stream" of the book's title. National events intruded on Foxton: A Roman villa was burned down by what we would now call insurgents; the Black Death devastated the area; the English Civil War made partisan demands on the populace. But the village's story is of persons and of families—individual homes traced, their furnishings deduced from the content of wills. In Parker's telling, Foxton springs to life, century by century.

5. The Shorter Pepys. By Samuel Pepys. Penguin Classics, 1993. Biography B Pepys

"Up, and to the office . . ." So far, so 21st century, but Samuel Pepys's office was of course that of the British Navy Board in the 1660s. His expansive, vivid diaries, published in several editions since they first appeared in 1825, are one of the most immediate and valuable accounts that we have of the habits and outlook of the mid-17th century, let alone the habits and outlook of a remarkable man. Pepys was clever, ambitious and wonderfully indiscreet. At one extreme, the diaries are an insight into the operation of the British navy and the labyrinthine politics of the times; at the other, they are a funny and candid portrait of Pepys's own family life, his incessant pursuit of women, his fractious relationship with his young wife. They also provide close-up accounts of the Fire of London and the Great Plague, presenting as well an enthralling picture of what it was like to live through it all as a privileged Londoner.

—Ms. Lively is the author of "Moon Tiger" and other novels. Her latest, "Family Album," has just been published by Viking.

1. The Boys' Crusade. By Paul Fussell. Modern Library, 2003 940.5421 F

In 1944, during the run-up to D-Day, two million young American men were given 17 weeks of basic training and shipped to Europe. Over the course of 11 months, from the Normandy landings to Germany's surrender, 135,000 U.S. infantrymen were killed and half a million wounded. Paul Fussell was among the soldiers who came home. He offers a brief, selective and forceful account of that period in "The Boys' Crusade"— and boys is what they largely were. The jacket of my copy shows the face of what one can only see as a child, swamped by his helmet. The book makes liberal use of eye-witness quotation—one soldier describes finding German corpses, "gray teeth, gray hands, worn boots, no identities . . . dead meat, nothing to grieve," and being "stupefied by the death we'd breathed"—an effect that plunges the reader into specific actions and the day-by-day routines of combat. But "The Boys' Crusade" also evokes the outlook of those teenagers—their blithe fidelity to the idea of America as the best and only modern country in the world, and their rapid exposure to the grim realities of an annihilating war.

2. The Last September. By Elizabeth Bowen. The Dial Press, 1929. FIC Bowen

This early novel by Elizabeth Bowen (1899-1973) is set in September 1920, at one of the "great houses" of the Anglo-Irish landowning Protestant families in southern Ireland. The central figure is Lois, a teenager staying on the estate, called Danielstown, with her aunt and uncle. There are tennis parties and dances—Lois loves a British officer from the nearby army station. But behind the story of this happy, innocent girl lurks another one: Ireland is in the midst of violent turmoil—guerrilla conflict between Irish rebels and the British troops who garrison the land. There are ambushes, reprisals, figures glimpsed in the darkness, rumors of arms caches. None of this is made explicit; instead, it surfaces in hints and clues that disturb the autumn program of social events. Until, at the end, there is the stark account of what came soon after: "A fearful scarlet ate up the hard spring darkness."

3. A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare. By James Shapiro. HarperCollins, 2005 822.33 Shakespeare S

James Shapiro places Shakespeare and his plays in their historical context, demonstrating how a yearlong burst of creative activity in 1599—"Henry V," "Julius Caesar," "As You Like It," the first draft of "Hamlet"—was prompted and fueled by what was actually happening at the time. England was threatened by Spain and its armada (possibly inspiring the "jittery soldiers" early in "Hamlet"), for instance, and Queen Elizabeth's favorite, the Earl of Essex, was pursuing a disastrous campaign to put down an Irish insurrection ("Henry V" mentions a general "from Ireland coming, / Bring rebellion broached on his sword"). The aging Elizabeth, with no successor waiting, feared assassination; "Julius Caesar" depicted the murder of a ruler. By finding public concerns reflected in the plays that Shakespeare was writing, Shapiro cunningly carries readers back to a single year and shows an extraordinary mind at work.

4. The Common Stream. By Rowland Parker. Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1975. 942.0657 P

Rowland Parker's publication of "The Common Stream" more than three decades ago was a pioneering instance of what is now known as micro-history. Parker was not a professional historian; he lived in the village of Foxton in eastern England and became fascinated by the visible presence of the past all around him. He walked, dug, ferreted in archives and eventually produced this remarkable reconstruction of how people had lived in one small part of the world for 2,000 years. The presence of water determined the beginnings of settlement, hence "the common stream" of the book's title. National events intruded on Foxton: A Roman villa was burned down by what we would now call insurgents; the Black Death devastated the area; the English Civil War made partisan demands on the populace. But the village's story is of persons and of families—individual homes traced, their furnishings deduced from the content of wills. In Parker's telling, Foxton springs to life, century by century.

5. The Shorter Pepys. By Samuel Pepys. Penguin Classics, 1993. Biography B Pepys

"Up, and to the office . . ." So far, so 21st century, but Samuel Pepys's office was of course that of the British Navy Board in the 1660s. His expansive, vivid diaries, published in several editions since they first appeared in 1825, are one of the most immediate and valuable accounts that we have of the habits and outlook of the mid-17th century, let alone the habits and outlook of a remarkable man. Pepys was clever, ambitious and wonderfully indiscreet. At one extreme, the diaries are an insight into the operation of the British navy and the labyrinthine politics of the times; at the other, they are a funny and candid portrait of Pepys's own family life, his incessant pursuit of women, his fractious relationship with his young wife. They also provide close-up accounts of the Fire of London and the Great Plague, presenting as well an enthralling picture of what it was like to live through it all as a privileged Londoner.

—Ms. Lively is the author of "Moon Tiger" and other novels. Her latest, "Family Album," has just been published by Viking.

Labels:

Book review,

Books,

England,

Ireland,

WW2

Saturday, November 7, 2009

Bluffing at the Highest Levels

When Harry S. Truman was sworn in to office, his poker buddies from the previous war were afraid he might stop playing now that he  had been "promoted." They need not have worried. The new chief executive even requisitioned a set of chips embossed with the presidential seal for use in the White House, though he tried to avoid being photographed gambling on its premises. The prudes of America would put up with only so much.

had been "promoted." They need not have worried. The new chief executive even requisitioned a set of chips embossed with the presidential seal for use in the White House, though he tried to avoid being photographed gambling on its premises. The prudes of America would put up with only so much.

Truman had learned to play cards from his aunt Ida and uncle Harry on their Missouri farm back in the 1890s. In a letter to Bess Wallace, the woman he was courting, in February 1911, the sincere 26-year-old suitor wrote, "I like to play cards and dance . . . and go to shows and do all the things [religious people] say I shouldn't, but I don't feel badly about it."

Truman's preference for poker over fussier country-club pastimes helps explain the temperament of "Give 'Em Hell Harry" during American labor disputes, hot wars with Japan and North Korea, and the cold war with Russia and China.

Throughout his 88 years, Truman used poker as both a personal and political means of expression. His motto, "The buck stops here," refers to the dealer's button or placeholder, because during the 19th century hunting knives with buckhorn handles often served that function. It was the president's folksy way of letting Americans know he was responsible for what happened on his watch.

James McManus is the author of "Positively Fifth Street." This essay is adapted from "Cowboys Full," recently published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

had been "promoted." They need not have worried. The new chief executive even requisitioned a set of chips embossed with the presidential seal for use in the White House, though he tried to avoid being photographed gambling on its premises. The prudes of America would put up with only so much.

had been "promoted." They need not have worried. The new chief executive even requisitioned a set of chips embossed with the presidential seal for use in the White House, though he tried to avoid being photographed gambling on its premises. The prudes of America would put up with only so much.Truman had learned to play cards from his aunt Ida and uncle Harry on their Missouri farm back in the 1890s. In a letter to Bess Wallace, the woman he was courting, in February 1911, the sincere 26-year-old suitor wrote, "I like to play cards and dance . . . and go to shows and do all the things [religious people] say I shouldn't, but I don't feel badly about it."

Truman's preference for poker over fussier country-club pastimes helps explain the temperament of "Give 'Em Hell Harry" during American labor disputes, hot wars with Japan and North Korea, and the cold war with Russia and China.

Throughout his 88 years, Truman used poker as both a personal and political means of expression. His motto, "The buck stops here," refers to the dealer's button or placeholder, because during the 19th century hunting knives with buckhorn handles often served that function. It was the president's folksy way of letting Americans know he was responsible for what happened on his watch.

James McManus is the author of "Positively Fifth Street." This essay is adapted from "Cowboys Full," recently published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Labels:

Book,

Books,

Poker,

Presidency,

President Truman

Friday, November 6, 2009

Precious

Sapphire. (1996). Push: a novel. New York : Alfred A. Knopf.

Sapphire. (1996). Push: a novel. New York : Alfred A. Knopf.This novel is now the basis for a film.

Precious: Based on the novel "Push" by Sapphire, with Gabourey Sidibe in the title role, opens Friday in selected cities.

Gabourey Sidibe (left) and Mo'Nique (right) star in the new movie 'Precious.'

Writing in the Wall Street Journal, Juan Williams, himself black, does not think highly of the movie or the book on which it is based:

The black imagination as revealed in gangster lit is centered on the world of drug dealers— "dough boys" who are heavy with drug money—and the get-rich-quick rappers and athletes who mimic the druggie lifestyle. And there are lots of "ghetto-fabulous" women, referring to themselves as bitches, carrying brand-name handbags and wearing big, gaudy jewelry. Attitude and anger are everything. The dispiriting word "nigger" is used freely by black characters talking about one another. There are guns and drive-by murders; hot sex that emphasizes the pleasure of getting it on with no strings attached; women without husbands and children without fathers; people who brag about being street-smart and then drop out of school and find themselves unemployed.

"Precious" is already a cultural event, then, whatever its box-office success turns out to be. The movie gives prominence to the subculture of gangster-lit novels, bringing them into the mainstream. Not only the best but the worst that can be said about these books is they are an authentic literary product of 21st-century black America. They are poorly written, poorly edited and celebrate the worst of black life.

Designated a Critic's Pick by the film reviewers of The Times.

Joe Morgenstern reviewed it well in the Journal.

One of the most telling moments of a shockingly beautiful film called "Precious" comes toward the end, and it's hardly more than a throwaway—the heroine glances at a mirror and sees herself. Until then mirrors have reflected her desperate fantasies of who she might be—a svelte blonde, a bejeweled black dancer or cover girl. That's because Claireece "Precious" Jones (Gabourey Sidibe) has found the sight of her physical self—like the plight of her spiritual self—unendurable. A 16-year-old African-American in the Harlem of 1987, she is mountainously obese, sexually and psychically abused, illiterate, almost mute and pregnant with her second child. The drama begins by giving her spirit voice—it's another notion of "A Beautiful Mind"—and follows her growth from a rageful child with a turbulent inner life to a formidable young woman with a life full of promise and hope.

The full, contractual title of the film, which was directed by Lee Daniels, is "Precious: Based on the Novel 'Push' By Sapphire." (Geoffrey Fletcher did the screen adaptation.) In addition to striking a blow for books and the written word, the title serves as a reminder that "Precious" is a work of fiction, by the African-American poet who calls herself Sapphire, and something of a fantasy in its own right—an inspirational fable about the power of kindness and caring. (The producers include Oprah Winfrey and Tyler Perry.)

View Full Image

FILM2_GOATS

Overture Films

George Clooney, below, is one of the stars of 'The Men Who Stare at Goats.'

FILM2_GOATS

FILM2_GOATS

That's not to diminish the fable's value, only to note the near-saintly devotion of an alternative-school teacher, Ms. Rain (Paula Patton), and a social worker, Ms. Weiss (Mariah Carey), and to acknowledge the time-lapse pace of the heroine's blossoming under their care. "Precious" is genuinely and irresistibly inspirational. If the filmmaking weren't so skillful and the acting weren't so consistently brilliant, you might mistake this production for a raw slice of life from a Third World country where movies can still be instruments of moral instruction and social change.

If Ms. Sidibe weren't playing the title role, it's hard to imagine what "Precious" would be. She doesn't play it, she invades and conquers it with concentrated energy and blithe humor. (Referring to the sophisticated Ms. Rain and her lesbian partner, Precious says, "They talk like a TV channel I don't watch.") And she's not the only spectacular attraction. The comedienne and actress Mo'Nique is stunningly effective as the heroine's monstrous mother, Mary, who makes a mockery of maternal instincts and comes undone in a ghastly confrontation that goes a long way toward explaining her monstrosity. This is a fine movie, and a deep one. It's about unearthing buried treasure.

Labels:

Criticism,

Fiction,

Film,

Movie review

Thursday, November 5, 2009

Googled

Auletta, Ken. (2009). Googled: the end of the world as we know it. New York : Penguin Press.

Auletta, Ken. (2009). Googled: the end of the world as we know it. New York : Penguin Press.In "Googled," New Yorker writer Ken Auletta tells the familiar story of the company's rapid transformation from Silicon Valley start-up to global corporation. As expected, we hear about the young Rollerblading employees at Google's Mountain View, Calif., headquarters, with its massage rooms, pool tables and free meals. But thanks to the unusual degree of access that the company granted the author—and thanks to his sharp eye—"Googled" also presents interesting new details. The book describes, for instance, Google's close relationship with former Vice President Al Gore—during a meeting with him, back in his hirsute phase after leaving office, Google executives showed their solidarity by donning fake beards.

Many companies and people are worried abouit the behemoth that is this company.

In contrast to all this corporate anxiety, consumers so far have been upbeat about the extraordinary power that Google wields. As Mr. Brin explains, Google's importance in people's lives comes from "determining what information they get to look at." Lawrence Lessig, who was an expert in the Microsoft antitrust case (and is now a professor at Harvard Law School), tells Mr. Auletta that Google will soon be more powerful than Microsoft ever was, since primacy in search gives the company unprecedented control over commerce and content.

Determining is a powerful word.

Google's favor turned Wikipedia into the world's leading reference source, but a few algorithm tweaks would easily send that torrent of traffic elsewhere. Mr. Lessig says that, for the moment, we take comfort from the fact that Google has been led by "good guys." But then he asks: "Why do we expect them to be good guys from now until the end of time?"

A tweak in the algorithm made Wikipedia be the top result in many searches.

Mr. Auletta notes that many successful companies have appeared "impregnable"—until they didn't. IBM once had a 70% share of the massive mainframe computer market. Then came antitrust action and the personal computer. A company expanding into as many arenas as Google is will almost certainly "wake up the bears," as Verizon Chairman and CEO Ivan Seidenberg puts it.

Problems for Google might lie beyond the horizon, but the immediate future promises more success: Google is well-positioned for the transition to "cloud computing," where software and data are stored online rather than on personal computers. Mr. Schmidt says that cloud computing will be "the defining technological shift of our generation." Accordingly, Google's greatest value creation probably still lies ahead.

Labels:

Book,

Book review,

Books,

Business,

Technology

Denialism

Specter, Michael. (2009). Denialism: how irrational thinking hinders scientific progress, harms the planet, and threatens our lives. New York: Penguin Press.

Excerpt: ‘Denialism’

“I always say that electricity is a fantastic invention,” the British economist Michael Lipton once told Michael Specter, whose bristling new book, “Denialism,” explores the dangerous ways in which scientific progress can be misunderstood. “But if the first two products had been the electric chair and the cattle prod,” Mr. Lipton continued, “I doubt that most consumers would have seen the point.”

The term “denialism,” used by Mr. Specter as an all-purpose, pop-sci buzzword, is defined by him as what happens “when an entire segment of society, often struggling with the trauma of change, turns away from reality in favor of a more comfortable lie.”

Creationism a prime example.

And whatever the merits of organic farming for societies that can afford it, what happens in places where food, land or water are scarce? There is a case to be made for agricultural methods that make the most efficient use of new technologies, and thus for genetically engineered crops that produce increased yields. But these are widely derided as Frankenfoods. Their ability to scare people and trigger blanket resistance is one of this book’s foremost illustrations of denialism in action.

It is people from societies with plenty that rail against genetically modified foods.

Wednesday, November 4, 2009

Start-up nation

Senor, Dan.(2009). Start-up nation: the story of Israel's economic miracle. New York : Twelve, 2009.

Senor, Dan.(2009). Start-up nation: the story of Israel's economic miracle. New York : Twelve, 2009.956.9405 S

Saw ad in today's Journal. HWPL, among other libraries, owns it.

From a Kirkus review, this phrase caught my eye: A pair of savvy policy wonks investigate how Israel has generated some notable economic wonders.In the face of the pervasive, virulent hostility of surrounding regimes, the young nation of Israel produces, per capita, more scientific papers than any other country. Amid frequent acts of terrorism, the Jewish state leads the world in percentage of GDP invested in research and development.

Saturday, October 31, 2009

Sleuth redux

Thursday, October 29, 2009

The emperor's club

I remember having seen this film. This time I took it out because of Emile Hirsch, the actor who plays Sedgewick Bell in this film and played Chris McCandles in Into the Wild.

I remember having seen this film. This time I took it out because of Emile Hirsch, the actor who plays Sedgewick Bell in this film and played Chris McCandles in Into the Wild.Good film. Kevin Klein is a superb actor. Hirsch does a very nice job as the rebellious son of the (fictitious) senior US Senator from West Virginia.

All the king's men

Third of three films with same title that HWPL owns. This one is the original 1949 film with Broderick Crawford playing the role Sean Penn would reprise in 2006.

Third of three films with same title that HWPL owns. This one is the original 1949 film with Broderick Crawford playing the role Sean Penn would reprise in 2006.Based on the book by Robert Penn Warren, it is the story of a man from the back country in Louisiana who runs for political office, loses, goes to law school, and is recruited to run for governor as a way to split the "hick" vote. Alerted to the scheme, he tosses away his prepared, fact-laden speech, and speechifies from the heart. Elected, as he does the people's work he enriches himself, losing his idealism and gaining materially. He also begins an affair with the at-times sweetheart of the newspaper reporter who is the other main character of the story (played by Jude Law in the 2006 version).

Curiously, all the characters in this 1949 version speak very plain English, with no accent; Sean Penn's character had a very thick accent. Another detail: 1949 ties were worn halfway down the chest by men.

Well done. Enjoyable.

Athens School

Kagan, Donald. (2009).

Kagan, Donald. (2009).Thucydides: The Reinvention of History

Viking, 257 pages, $26.95

Only because of Thucydides' "History of the Peloponnesian War"—with his radical claims of exercising a new rationality and, most grandiloquently, of writing a "thing for all time"—did a typically messy military contest based on money, influence, bloody-mindedness and happenstance become interpreted and reinterpreted as though it were a religious revelation. Communists and anticommunists, leftists and neocons, anti-imperialists and empire builders have all fought to recruit the great Athenian as their ally.

Donald Kagan, a veteran Yale professor of classics and ancient history, has himself taken part in these arguments for almost a half-century. His own four-volume history of the Peloponnesian War is a classic of modern scholarship. Now, with "Thucydides: The Reinvention of History," Mr. Kagan has produced what reads like the last word on the man, a nuanced and subtle account of a subject that has so often been treated in a spirit of high partisanship.

Mr. Kagan has no time for worshiping Thucydides' eternal rational purity, as students were once so rigorously taught to do. But he is not the first skeptic on this front: Scholars have insisted for the past quarter-century—most recently in Simon Hornblower's magisterial three-volume "A Commentary on Thucydides," completed earlier this year—that Thucydides was a master of drama as much as of science, a master of stadium rhetoric as much as of empirical reporting. It is dangerous to see him, as Mr. Kagan puts it, as "a disembodied mind." He was "a passionate individual" writing about "the greatness of his city and its destruction."

Mr. Kagan finishes up with an observation that foreign-policy debaters would do well to keep in mind: "A hegemonic state may gain power by having allies useful in war, but reliance on those states may compel the hegemonic power to go to war against its own interests." The disastrous misadventure of the Athenians in Sicily began, Mr. Kagan writes, with "the entreaties of their small, far-off allies." As he notes, it was Bismarck who once said that in a world of competing alliances it is essential "to be the rider, not the horse."

Thucydides' "History," says Mr. Kagan, shows "how difficult an assignment" the rider faces. His own book is a valuable guide to the ways in which the Peloponnesian War can—and cannot—be used to guide modern thinking.

Labels:

Ancient Greece,

Book review,

History

Saturday, October 24, 2009

All the King's Men

One of three films with the same title at the Hewlett Library. This one takes place in England and Turkey during 1915. A batallion is raised from the staff that works at the royal house in Sandringham, Norfolk, England, and goes to fight in Gallipoli, Turkey. Despite their excellent training, the soldiers are unprepared for the extreme heat, and without ample supplies, including accurate maps. In the end, they enter a battle where they are routed. The film shows many British soldiers being massacred, shot in the head. Turks sure don't come off well.

One of three films with the same title at the Hewlett Library. This one takes place in England and Turkey during 1915. A batallion is raised from the staff that works at the royal house in Sandringham, Norfolk, England, and goes to fight in Gallipoli, Turkey. Despite their excellent training, the soldiers are unprepared for the extreme heat, and without ample supplies, including accurate maps. In the end, they enter a battle where they are routed. The film shows many British soldiers being massacred, shot in the head. Turks sure don't come off well.Maggie Smith plays Queen Alexandra with her usual aplomb. David Jason plays Captain Frank Beck, the Sandringham estate manager, a favorite of the Queen, whom, at first, is denied passage to the fighting by King George (Georgie, his mother, Alexandra, calls him).

Nicely done.

Friday, October 23, 2009

All the King's Men

Remake of the 1949 film, updated. Sean Penn plays the upcountry bumpkin who tries to expose corruption, loses an election, and is vindicated by an ensuing tragedy. He is drafted to run for governor some few years later, unaware he is being used a way to split to hick vote. Alerted to the sham, he tosses away his dry speech and let loose with appeals to the pride of the forgotten.

Remake of the 1949 film, updated. Sean Penn plays the upcountry bumpkin who tries to expose corruption, loses an election, and is vindicated by an ensuing tragedy. He is drafted to run for governor some few years later, unaware he is being used a way to split to hick vote. Alerted to the sham, he tosses away his dry speech and let loose with appeals to the pride of the forgotten.Jude Law is superb as the hard-bitten reporter who joins forces with the reformist politician. Jack Burden also has a romantic link that has never been brought to resolution; that role is played by Kate Winslet, and I thought little of the role or her acting.

Anthony Hopkins plays the thorn in Willie Stark's side. He doesn't quite airmail it in, but his acting seems at least in part done by rote. He's good, sure. Penn is excellent, but it is Law that really shines.

Labels:

American history,

Film,

Literature,

Louisiana

Tuesday, October 20, 2009

A Raconteur of Nature’s Back Story

Richard Dawkins, with a statue of Charles Darwin at the Natural History Museum in London.

The Greatest Show on Earth,' by Richard Dawkins: Evolution All Around (October 11, 2009)

Richard Dawkins’s Web Site

If there were a celebrity of the evolutionary world, Mr. Dawkins would certainly be it. His best-selling books — including “The Selfish Gene” and “The Blind Watchmaker,” laying out his case for a gene-centered view of evolution — have gone a long way toward making evolutionary biology accessible to a wide audience.

He lectures to sell-out audiences, receives standing ovations and regularly places in the Top 10 on Prospect magazine’s annual list of the world’s 100 Top Public Intellectuals. His latest book, “The Greatest Show on Earth: The Evidence for Evolution” (Free Press), has been on the New York Times nonfiction best-seller list for three weeks.

For one thing, 2009 is the 200th anniversary of Darwin’s birth, and the 150th anniversary of his book “On the Origin of Species.” For another, “The Greatest Show on Earth” is Mr. Dawkins’s own “missing link,” he said, filling in the gaps in his previous works. While earlier books assumed that readers understood the scientific basis for evolution, this one lays it out directly.

The Greatest Show on Earth,' by Richard Dawkins: Evolution All Around (October 11, 2009)

Richard Dawkins’s Web Site

If there were a celebrity of the evolutionary world, Mr. Dawkins would certainly be it. His best-selling books — including “The Selfish Gene” and “The Blind Watchmaker,” laying out his case for a gene-centered view of evolution — have gone a long way toward making evolutionary biology accessible to a wide audience.

He lectures to sell-out audiences, receives standing ovations and regularly places in the Top 10 on Prospect magazine’s annual list of the world’s 100 Top Public Intellectuals. His latest book, “The Greatest Show on Earth: The Evidence for Evolution” (Free Press), has been on the New York Times nonfiction best-seller list for three weeks.

For one thing, 2009 is the 200th anniversary of Darwin’s birth, and the 150th anniversary of his book “On the Origin of Species.” For another, “The Greatest Show on Earth” is Mr. Dawkins’s own “missing link,” he said, filling in the gaps in his previous works. While earlier books assumed that readers understood the scientific basis for evolution, this one lays it out directly.

Monday, October 19, 2009

You can count on me

Nice film. Enjoyable. IMDb has it being filmed in Phoenicia and Margaretville.

Nice film. Enjoyable. IMDb has it being filmed in Phoenicia and Margaretville.Errors in geography: The film is set in Scottsville, New York, which is in the far west of the state, south of Rochester. However, a sign is seen for NY Rt28, which does not run anywhere near Scottsville. This is because the film was shot in and around Phonecia, New York, through which NY Rt28 runs.

I saw the signs for Route 28 and Route 30, and wondered about the location.

Saturday, October 17, 2009

First Circle

Excerpt: 'In the First Circle'

Excerpt: 'In the First Circle'I well remember reading this book, and others, by Solzhenitsyn. I greatly liked this and Cancer Ward.

It has taken a half-century for English-language readers to receive the definitive text of "In the First Circle," the best novel by one of the greatest authors of our time. Such is the fate of art created under a totalitarian regime. But now it is finally available in the West as the author envisioned it. The English translator is Harry T. Willetts, renowned for combining fidelity to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's rich, complex Russian with supple equivalents in English prose and the only person Solzhenitsyn fully trusted to render his fiction into English.

Solzhenitsyn wrote the book under exceptionally difficult circumstances. In 1953, as he was about to emerge from eight years in the gulag, the Soviet prison-camp system, he was diagnosed with cancer. Consigned to internal exile in Kazakhstan, he found work as a schoolteacher but devoted every spare moment to writing. In 1958, he completed the first draft of "In the First Circle," a novel, set during Stalin's rule, about the effects of incarceration and forced labor on the minds and souls of innocent and intelligent men. He immediately put it through two revisions.

"In the First Circle" is the first work by Solzhenitsyn to go to press in English since he died last year at age 89. A major writer's death fosters reflection on his overall achievement, so this is the perfect time to reconsider the novel now that it is finally available to us as the author intended. A literary classic is defined as a book still read a century after appearing. On that basis one might say that the book has already had a 40-year head start on fulfilling that definition, given the acclaim with which the bowdlerized text has been received since its appearance in the West in 1968.

An intriguing intimation of the prospects for this version comes from the Russian experience with the canonical text. In 2006 a Russian television network presented serializations of classic Russian novels by Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Pasternak, Bulgakov and Solzhenitsyn. Fifteen million viewers tuned in to each installment of "In the First Circle."

Labels:

Book review,

Books,

Literature,

Russia

Thursday, October 15, 2009

Fireboat

Kalman, Maira. (2002). Fireboat: the heroic adventures of the John J. Harvey. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons.

Kalman, Maira. (2002). Fireboat: the heroic adventures of the John J. Harvey. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons.[J 974.7104 K]

This wonderful little children's book was mentioned by Jessica DuLong in her book, My River Chronicles, [917.473 D] which I am currently reading.

What crap

Hoax

Fairly good. Gere remarkably resembled Irving down to a tee, as I remember. Harden wasn't very believable as Irving's wife; even though her English accent was well done, it seemed somehow, well, fake. Molina was good. After watching Elegy for only a few minutes the night before, and disgustedly turning it off, Hoax was a welcome respite.

Fairly good. Gere remarkably resembled Irving down to a tee, as I remember. Harden wasn't very believable as Irving's wife; even though her English accent was well done, it seemed somehow, well, fake. Molina was good. After watching Elegy for only a few minutes the night before, and disgustedly turning it off, Hoax was a welcome respite.

Wednesday, October 14, 2009

Monk

Kelley, Robin D. G. (2009). Thelonious Monk: the life and times of an American original. New York: Free Press.

Kelley, Robin D. G. (2009). Thelonious Monk: the life and times of an American original. New York: Free Press.New book. Reviewed in the Times on 18 October.

Thelonious Monk, the great American jazz artist, during the first half of his junior year at Stuyvesant High School in New York, showed up in class only 16 out of 92 days and received zeros in every one of his subjects. His mother, Barbara Monk, would not have been pleased. She had brought her three children to New York from North Carolina, effectively leaving behind her husband, who suffered bad health, and raising the family on her own, in order that they might receive a proper education. But Mrs. Monk, like a succession of canny, tough-minded, loving and very indulgent women in Thelonious Monk’s life, understood that her middle child had a large gift and was put on this earth to play piano. Presently, her son was off on a two-year musical tour of the United States, playing a kind of sanctified R & B piano in the employ, with the rest of his small band, of a traveling woman evangelist.

That was the original Stuyvesant, on 15th Street, between 1st and 2nd Avenues, on the south border of Stuyvesant Square.

The brilliant pianist Mary Lou Williams, seven years Monk’s senior and working at the time for Andy Kirk’s Clouds of Joy orchestra, heard Monk play at a late-night jam session in Kansas City in 1935. Monk, born in 1917, would have been 18 or so at the time. When not playing to the faithful, he sought out the musical action in centers like Kansas City. Williams would later claim that even as a teenager, Monk “really used to blow on piano. . . . He was one of the original modernists all right, playing pretty much the same harmonies then that he’s playing now.”

Mary Lou Williams is brilliant.

Robin D. G. Kelley, in his extraordinary and heroically detailed new biography, “Thelonious Monk,” makes a large point time and time again that Monk was no primitive, as so many have characterized him. At the age of 11, he was taught by Simon Wolf, an Austrian émigré who had studied under the concertmaster for the New York Philharmonic. Wolf told the parent of another student, after not too many sessions with young Thelonious: “I don’t think there will be anything I can teach him. He will go beyond me very soon.” But the direction the boy would go in, after two years of classical lessons, was jazz.

Monk was well enough known and appreciated in his lifetime to have appeared on the cover of the Feb. 28, 1964, issue of Time magazine. He was 46 at the time, and after many years of neglect and scuffling had become one of the principal faces and sounds of contemporary jazz. The Time article, by Barry Farrell, is, given the vintage and target audience, well done, both positive and fair, and accurate in the main. But it does make much of its subject’s eccentricities, and refers to Monk’s considerable and erratic drug and alcohol use. This last would have raised eyebrows in the white middle-class America of that era.

Monk was well enough known and appreciated in his lifetime to have appeared on the cover of the Feb. 28, 1964, issue of Time magazine. He was 46 at the time, and after many years of neglect and scuffling had become one of the principal faces and sounds of contemporary jazz. The Time article, by Barry Farrell, is, given the vintage and target audience, well done, both positive and fair, and accurate in the main. But it does make much of its subject’s eccentricities, and refers to Monk’s considerable and erratic drug and alcohol use. This last would have raised eyebrows in the white middle-class America of that era.There will be shapelier and more elegantly written biographies to come — Monk, the man and the music, is an endlessly fascinating subject — but I doubt there will be a biography anytime soon that is as textured, thorough and knowing as Kelley’s. The “genius of modern music” has gotten the passionate, and compassionate, advocate he deserves.

Illustration by Joe Ciardiello - Thelonious Monk

Spooner

Pete Dexter’s new novel, “Spooner,” draws heavily on his own life.

October 14, 2009

Write What You Know: Reflections of a Wayward Soul

By ERIC KONIGSBERG

CLINTON, Wash. — When Pete Dexter invites you to his house for dinner at 6 p.m. but says it’s fine to show up any time before 10, you can tell that he means it because he adds, “I’ve been late my whole life.”

Mr. Dexter’s seventh novel, “Spooner,” has just come out three years late. The blame lies with a case of prolixity. “I just couldn’t stop writing — I didn’t want to let the thing go,” he said last week. He typed 800 pages before pressure from his publisher forced him to prune it and be finished. But not completely: Mr. Dexter, whose previous novels include “The Paperboy” and “Paris Trout,” which won the National Book Award for fiction in 1988, has found a bunch of things he doesn’t like in the published book, and is hoping for the chance to tweak a few for the paperback edition.

“Spooner” (Grand Central Publishing), which clocks in at around 460 pages, thanks to the wonders of dense pagination, is in many ways a departure for Mr. Dexter, who has made a career of spare prose, tight plots and stories that center on a single violent act and its effects on the concentric circles that can make anyplace (a small town in the Deep South, postwar Beverly Hills or the old West of Wild Bill Hickok) feel gothic. This time Mr. Dexter has spun a discursive cradle-to-grave yarn about a well-meaning but wayward soul and his saintly stepfather.

For Mr. Dexter, whose father died when he was 2 and who was reared by his stepfather, the story — unlike his previous fiction — is also largely autobiographical. Much like Mr. Dexter’s real stepfather, Thurlo Tollefson, the stepfather in “Spooner,” Calmer Ottosson, is a military-school teacher who takes in a widow’s two young children and then has two sons with her.

“It dawned on me when I was writing this that my stepfather never let on that he preferred his real sons to me, but how could he not have?” Mr. Dexter said. “I never understood how you could help but love one child more than another in the first place, which is part of why my wife and I only had one.”

Mr. Dexter and his wife of 30 years, Dian — known to readers of his books’ dedication pages simply as “Mrs. Dexter” — live here on Whidbey Island in a large Arts and Crafts bungalow on 10 wooded acres overlooking Puget Sound. On the land are three tractors and a Mercedes, all of which are operated mainly by Mrs. Dexter.

“Mrs. Dexter drives cars I don’t even get to look at,” he said. (“He likes to eat in the car and throw things on the floor,” she explained.)

Mr. Dexter, a hipless and round-shouldered 66-year-old, is allowed to use the barbecue. He emptied the contents of one and a half bottles of Kraft Catalina salad dressing onto a large salmon filet, then went outside to the patio grill armed with a flashlight. He wore elastic-waist shorts that his wife kept reminding him to hitch up, tennis shoes without socks, a Hawaiian shirt with sailboats on it and a pink Yankees cap. He looked like Oscar Madison in Miami Beach.

Much like the protagonist of “Spooner,” Mr. Dexter had a youth full of broken bones and bodily wear and tear (he has had “six or seven” hip replacements, he said) and not much academic engagement. While the three other children in his blended family went off to Harvard, Yale and the University of Chicago, he drifted in and out of enrollment at the University of South Dakota and took eight years to earn a diploma.

He was working odd jobs in Florida when he walked by the offices of what is now The South Florida Sun Sentinel in Fort Lauderdale and saw a sign advertising a reporter position.

“I looked around the place, and it just looked like heaven,” Mr. Dexter said. “For one thing, it was air-conditioned. The next day I was a reporter with 11 beats: poverty issues, juvenile issues, hospitals, tomatoes — they were a big crop down there.”

The path eventually led him to The Philadelphia Daily News, where he became a popular city columnist. His conversion to fiction came about not only by accident, but also by catastrophe; an iteration of it occurs in the saga of Warren Spooner, the title character in his new book. Mr. Dexter visited a neighborhood bar to make peace with a man who had taken offense at a column he wrote. Instead, the man and his friends took baseball bats and crowbars to Mr. Dexter and a friend, the heavyweight boxer Randall (Tex) Cobb, nearly killing Mr. Dexter.

Mr. Dexter’s leg was broken, his back was fractured in three places, and cuts on his scalp required 90 stitches. After that he was no longer interested in late nights in bars in search of column material.

“Something happened to my brain that made alcohol taste like acid for a couple of years,” he said. “And all the stuff that you can tolerate when you’re drinking — all the hugging and yelling and the way people spit when they’re talking to you — wasn’t so much fun. All of a sudden I’m waking up at 9 in the morning instead of noon, and I’ve got a couple of hours to write something else before I get to work on my column.”

None of his novels have been big sellers, he said, though all but “Spooner” have been optioned for films or television, “which means you more than break even.” He wrote the television adaptation of “Paris Trout,” and the scripts for several big-budget movies, including “Rush,” “Mulholland Falls” and “Michael,” which was directed by Nora Ephron and starred John Travolta as an unorthodox angel.

Ever since a computer glitch erased the entire middle section of “Paris Trout” on the day he finished writing it, Mr. Dexter has mistrusted technology. “It was 122 pages when it went down, and after I rewrote it for a couple of months, it came back at 112,” he said. “I’m positive those were the best 10 pages I ever wrote.”

Though he has friends who are writers, among them Richard Russo and Padgett Powell, he generally has a hard time with the success of others. “Jealousy’s the wrong word for what I usually feel,” he said. “It’s closer to hoping they get hit by a car.”

Around 11 p.m., with dinner over, Mr. Dexter prepared to head across the driveway to the guesthouse, where he writes. “I usually work really well from about midnight to 4 in the morning, when it’s really quiet,” he said. He has started a new novel based on an incident in the 1910s, when a rogue circus elephant got loose and rampaged through a town in South Dakota.

“I saw something about it in a museum five or six years ago, and the first line of the novel came to me then,” Mr. Dexter said.

The line establishes that somebody other than the elephant keeper is sleeping with the elephant keeper’s wife, though “sleeping with” aren’t the words Mr. Dexter has chosen.

“I’m in a phase of heavy research,” he said. “Right now, I’ve literally got 8 or 10 books about elephants I’m in the middle of reading. The trouble about elephant books is that they’re inevitably sad. It always comes down to people killing the elephants.”

SPOONER

By Pete Dexter

469 pp. Grand Central Publishing. $26.99

eptember 27, 2009

Objects in the Mirror

By LIESL SCHILLINGER

Skip to next paragraph

SPOONER

By Pete Dexter

469 pp. Grand Central Publishing. $26.99

Everyone has heard of writer’s block, a condition that plagues authors great and small. Yet the affliction takes more forms than is commonly supposed. For some sufferers, it manifests as sitting-in-the-chair block, a disinclination to hunker down and get to work. For others it’s total creative shutdown. But the prolific Pete Dexter suffers from neither. For the past five years or so, as he worked on his memoirish novel, “Spooner,” Dexter was plagued by a reverse form of the malady: call it “stopping block.” In a note to readers in the advance edition of “Spooner,” Dexter explains that he turned in his novel more than three years late not because he was stymied about what to write but because he was bedeviled by the question of what to leave out. He simply couldn’t stem the flood of story that poured forth as he chronicled the misadventures of Warren Spooner from his birth in Milledgeville, Ga., in 1956 (where Dexter, born 13 years earlier, also grew up), to his failed early attempts at employment and marriage in Florida (another echo from Dexter’s past), to Philadelphia, where Spooner (like Dexter) acquired a happy second marriage and a career as a newspaper columnist until (like Dexter) he was violently beaten by thugs who didn’t like his writing. By the time he had transported Spooner (now a novelist) to remote Whidbey Island, in Puget Sound (where the author now lives), Dexter had written hundreds more pages than he’d intended.

“I could have kept this up for another five years,” he admits. Instead, he spent a year trimming 250 excess pages, then reluctantly released the “Spooner” manuscript, heeding the dictate of his character Yardley Acheman, the ruthless investigative journalist from “The Paperboy” (1995): “You have to let go of it to get it done.” In that book, Acheman’s instincts proved wrong. His haste to publish earned him a Pulitzer, but also sprung a swamp-dwelling sociopath from prison and brought embarrassment to his paper and his writing partner — not to mention an extra corpse or two to Moat County.

Lucky for Dexter, the consequences of the tardy, yet (in his judgment) unfinished release of Warren Spooner’s wonderful, horrible life are less fraught, even felicitous. And it’s no wonder that this newsman-turned-novelist, known for his spare writing style and taut plotting, was daunted by the task of condensing the action-packed chronicle of his alter ego — a man who, like another Dexter character, Miller Packard (from the 2003 novel “Train”), sees himself “from a distance” and mistrusts introspection. “Sometimes, when he thought about it,” Dexter wrote of Packard, “it seemed like he’d been someplace else, watching himself, for most of his life.” The same could be said of Spooner. But in some 500 pages, Dexter brings Warren Spooner to ground and to life with uncharacteristic expansiveness and tenderness.

“Spooner” is a family epic that digs out the emotions packed in memory’s earliest bonds — guilt, resentment, loyalty and love. For Spooner, the guilt and resentment attach mostly to his mother, a querulous asthmatic who impressed upon him the unique agony of his birth (which his better-looking twin brother failed to survive), and who let him know that his existence was a continuing source of distress — crying out “God, how long can I stand it?” and weeping into a dish towel or a pillow over the various miseries of motherhood. His loyalty and love (at least until he becomes a husband and father) attach to a series of unappetizing dogs and to his stepfather. Spooner’s biological father died when his son was a baby, but the boy was spared a fatherless childhood by the arrival in Milledgeville of Calmer Ottosson, a disgraced young naval commander whose seafaring career was cut short by the botched burial-at-sea of an obese congressman. To the great fortune of what remained of the Spooner family — Spooner; his clever older sister, Margaret; and his mother, Lily — Calmer ended up teaching school in Milledgeville and speedily married Lily. Handy and dutiful, nurturing but reticent, Calmer instills in the boy a sturdy, quiet code of male behavior. At the age of 4, Spooner hungrily soaks up Calmer’s example. When he sees his sister take their future stepfather’s hand, he follows suit: “Without knowing he was doing it,” Dexter writes, “Spooner reached for a hand too, and got Calmer’s little finger instead, and they walked that way to the end of the block, and then Calmer stopped and gently pried him loose. ‘Men don’t hold hands,’ he said.” Oh, the pity of masculine detachment!

But when Spooner perversely plants himself in an anthill crawling with thousands of stinging insects, it’s Calmer who rescues him, brushes the ants off him and bathes him, soothing, “Easy does it . . . just take it easy,” and it’s Calmer who watches over the sickbed. Years later, Spooner remembers “the man sitting in the dark on the chest beside the bed, helpless, and the child lying in the dark beneath him, pretending to sleep, also helpless” — the two united in their manly vow of silence, and in their unspoken affection. When Spooner, in late adolescence, briefly becomes a baseball star, it’s Calmer who goes to his games, Calmer who tells him to keep his signing bonus from the Cincinnati Reds rather than turn it over to the family (because “you can never tell when you might need it”), and Calmer whose face Spooner sees when he awakes from surgery on his shattered, irretrievably wrecked pitching arm.

These stoical lessons help Spooner weather the adversities he meets once he’s on his own — like his first boss, in Florida, a “clean-cut, low-living sort of human outcast named Stroop” who sells baby pictures door to door, and tickles Spooner with a cattle prod before handing over his paycheck. (Spooner submits to the overture to get the money, then quits and becomes a journalist.) Among Spooner’s other adversaries are the stream of women who warm to, then instantly cool on him, “like they’d wandered into a pet store and almost bought a monkey,” and the men he meets with in Philadelphia to apologize for writing an article they disliked, who break his back and bash in his face. “Spooner had empathy to a fault, perhaps had learned it from Calmer.”

Empathy certainly betrayed him in Philadelphia. And yet, any reader who knows Dexter’s biography, so closely entangled with Spooner’s, knows that it’s this very attribute, and the horrendous 1981 attack it provoked, that moved Dexter to start writing novels. If it’s a fault, it’s one that has been redeemed in both blood and ink.

“Spooner” has little in common with Dexter’s previous work. Typically, in his books and screenplays (notably “Rush” and “Mulholland Falls”) he coils a psychologically charged drama around one signal incident or relationship — as he did in his 1988 novel “Paris Trout” (winner of the National Book Award), which anatomized the racism and bubba politics of a small Southern town in the wake of the killing of an innocent black girl. The concentrated nature of each story’s core subject limited the span of its telling, while Dexter’s insight into dark human behavior and his journalistic eye for the small, brutal detail made even short sentences dense with buried inference. But in “Spooner,” he unearths the experiences that underlie this nuanced sensibility, exposing the familial archetypes that shade his characters and directly engaging the potent emotions that emerge obliquely in his other books. It’s a conversational novel, roving and inclusive, packed with Southern color and Northeastern grit, with rueful reflection and the contretemps of daily life that can’t be avoided even on a remote island in the Puget Sound. But — like Spooner and like Miller Packard — Dexter shies away from analyzing too closely the meaning of the events he describes, letting incident and anecdote replace allusion. As Dexter follows Spooner across the decades and across the continent, from a makeshift delivery room in Georgia to the Pacific Northwest, he weaves in Calmer’s progress as well — his career disappointments, his wife’s unhappinesses and his eventual move to Whidbey Island, where stepson becomes caretaker to stepfather, to the extent that proud, uncomplaining Calmer will permit.

The story of “Spooner” is the story of how Calmer made Spooner, and of how Spooner made himself. It’s also the story of why Pete Dexter writes, and of why he couldn’t stop writing this particular book. He ended his novel “The Paperboy” with the words: “There are no intact men.” With “Spooner,” he demonstrates the impulse that keeps writers at their task: the longing to reassemble the whole; to see, however belatedly, who a person was, or could have been.

Liesl Schillinger is a regular contributor to the Book Review.

October 14, 2009

Write What You Know: Reflections of a Wayward Soul

By ERIC KONIGSBERG

CLINTON, Wash. — When Pete Dexter invites you to his house for dinner at 6 p.m. but says it’s fine to show up any time before 10, you can tell that he means it because he adds, “I’ve been late my whole life.”

Mr. Dexter’s seventh novel, “Spooner,” has just come out three years late. The blame lies with a case of prolixity. “I just couldn’t stop writing — I didn’t want to let the thing go,” he said last week. He typed 800 pages before pressure from his publisher forced him to prune it and be finished. But not completely: Mr. Dexter, whose previous novels include “The Paperboy” and “Paris Trout,” which won the National Book Award for fiction in 1988, has found a bunch of things he doesn’t like in the published book, and is hoping for the chance to tweak a few for the paperback edition.

“Spooner” (Grand Central Publishing), which clocks in at around 460 pages, thanks to the wonders of dense pagination, is in many ways a departure for Mr. Dexter, who has made a career of spare prose, tight plots and stories that center on a single violent act and its effects on the concentric circles that can make anyplace (a small town in the Deep South, postwar Beverly Hills or the old West of Wild Bill Hickok) feel gothic. This time Mr. Dexter has spun a discursive cradle-to-grave yarn about a well-meaning but wayward soul and his saintly stepfather.

For Mr. Dexter, whose father died when he was 2 and who was reared by his stepfather, the story — unlike his previous fiction — is also largely autobiographical. Much like Mr. Dexter’s real stepfather, Thurlo Tollefson, the stepfather in “Spooner,” Calmer Ottosson, is a military-school teacher who takes in a widow’s two young children and then has two sons with her.

“It dawned on me when I was writing this that my stepfather never let on that he preferred his real sons to me, but how could he not have?” Mr. Dexter said. “I never understood how you could help but love one child more than another in the first place, which is part of why my wife and I only had one.”

Mr. Dexter and his wife of 30 years, Dian — known to readers of his books’ dedication pages simply as “Mrs. Dexter” — live here on Whidbey Island in a large Arts and Crafts bungalow on 10 wooded acres overlooking Puget Sound. On the land are three tractors and a Mercedes, all of which are operated mainly by Mrs. Dexter.

“Mrs. Dexter drives cars I don’t even get to look at,” he said. (“He likes to eat in the car and throw things on the floor,” she explained.)

Mr. Dexter, a hipless and round-shouldered 66-year-old, is allowed to use the barbecue. He emptied the contents of one and a half bottles of Kraft Catalina salad dressing onto a large salmon filet, then went outside to the patio grill armed with a flashlight. He wore elastic-waist shorts that his wife kept reminding him to hitch up, tennis shoes without socks, a Hawaiian shirt with sailboats on it and a pink Yankees cap. He looked like Oscar Madison in Miami Beach.

Much like the protagonist of “Spooner,” Mr. Dexter had a youth full of broken bones and bodily wear and tear (he has had “six or seven” hip replacements, he said) and not much academic engagement. While the three other children in his blended family went off to Harvard, Yale and the University of Chicago, he drifted in and out of enrollment at the University of South Dakota and took eight years to earn a diploma.

He was working odd jobs in Florida when he walked by the offices of what is now The South Florida Sun Sentinel in Fort Lauderdale and saw a sign advertising a reporter position.

“I looked around the place, and it just looked like heaven,” Mr. Dexter said. “For one thing, it was air-conditioned. The next day I was a reporter with 11 beats: poverty issues, juvenile issues, hospitals, tomatoes — they were a big crop down there.”

The path eventually led him to The Philadelphia Daily News, where he became a popular city columnist. His conversion to fiction came about not only by accident, but also by catastrophe; an iteration of it occurs in the saga of Warren Spooner, the title character in his new book. Mr. Dexter visited a neighborhood bar to make peace with a man who had taken offense at a column he wrote. Instead, the man and his friends took baseball bats and crowbars to Mr. Dexter and a friend, the heavyweight boxer Randall (Tex) Cobb, nearly killing Mr. Dexter.

Mr. Dexter’s leg was broken, his back was fractured in three places, and cuts on his scalp required 90 stitches. After that he was no longer interested in late nights in bars in search of column material.

“Something happened to my brain that made alcohol taste like acid for a couple of years,” he said. “And all the stuff that you can tolerate when you’re drinking — all the hugging and yelling and the way people spit when they’re talking to you — wasn’t so much fun. All of a sudden I’m waking up at 9 in the morning instead of noon, and I’ve got a couple of hours to write something else before I get to work on my column.”

None of his novels have been big sellers, he said, though all but “Spooner” have been optioned for films or television, “which means you more than break even.” He wrote the television adaptation of “Paris Trout,” and the scripts for several big-budget movies, including “Rush,” “Mulholland Falls” and “Michael,” which was directed by Nora Ephron and starred John Travolta as an unorthodox angel.

Ever since a computer glitch erased the entire middle section of “Paris Trout” on the day he finished writing it, Mr. Dexter has mistrusted technology. “It was 122 pages when it went down, and after I rewrote it for a couple of months, it came back at 112,” he said. “I’m positive those were the best 10 pages I ever wrote.”

Though he has friends who are writers, among them Richard Russo and Padgett Powell, he generally has a hard time with the success of others. “Jealousy’s the wrong word for what I usually feel,” he said. “It’s closer to hoping they get hit by a car.”

Around 11 p.m., with dinner over, Mr. Dexter prepared to head across the driveway to the guesthouse, where he writes. “I usually work really well from about midnight to 4 in the morning, when it’s really quiet,” he said. He has started a new novel based on an incident in the 1910s, when a rogue circus elephant got loose and rampaged through a town in South Dakota.

“I saw something about it in a museum five or six years ago, and the first line of the novel came to me then,” Mr. Dexter said.

The line establishes that somebody other than the elephant keeper is sleeping with the elephant keeper’s wife, though “sleeping with” aren’t the words Mr. Dexter has chosen.

“I’m in a phase of heavy research,” he said. “Right now, I’ve literally got 8 or 10 books about elephants I’m in the middle of reading. The trouble about elephant books is that they’re inevitably sad. It always comes down to people killing the elephants.”

SPOONER

By Pete Dexter

469 pp. Grand Central Publishing. $26.99

eptember 27, 2009

Objects in the Mirror

By LIESL SCHILLINGER

Skip to next paragraph

SPOONER

By Pete Dexter

469 pp. Grand Central Publishing. $26.99

Everyone has heard of writer’s block, a condition that plagues authors great and small. Yet the affliction takes more forms than is commonly supposed. For some sufferers, it manifests as sitting-in-the-chair block, a disinclination to hunker down and get to work. For others it’s total creative shutdown. But the prolific Pete Dexter suffers from neither. For the past five years or so, as he worked on his memoirish novel, “Spooner,” Dexter was plagued by a reverse form of the malady: call it “stopping block.” In a note to readers in the advance edition of “Spooner,” Dexter explains that he turned in his novel more than three years late not because he was stymied about what to write but because he was bedeviled by the question of what to leave out. He simply couldn’t stem the flood of story that poured forth as he chronicled the misadventures of Warren Spooner from his birth in Milledgeville, Ga., in 1956 (where Dexter, born 13 years earlier, also grew up), to his failed early attempts at employment and marriage in Florida (another echo from Dexter’s past), to Philadelphia, where Spooner (like Dexter) acquired a happy second marriage and a career as a newspaper columnist until (like Dexter) he was violently beaten by thugs who didn’t like his writing. By the time he had transported Spooner (now a novelist) to remote Whidbey Island, in Puget Sound (where the author now lives), Dexter had written hundreds more pages than he’d intended.

“I could have kept this up for another five years,” he admits. Instead, he spent a year trimming 250 excess pages, then reluctantly released the “Spooner” manuscript, heeding the dictate of his character Yardley Acheman, the ruthless investigative journalist from “The Paperboy” (1995): “You have to let go of it to get it done.” In that book, Acheman’s instincts proved wrong. His haste to publish earned him a Pulitzer, but also sprung a swamp-dwelling sociopath from prison and brought embarrassment to his paper and his writing partner — not to mention an extra corpse or two to Moat County.

Lucky for Dexter, the consequences of the tardy, yet (in his judgment) unfinished release of Warren Spooner’s wonderful, horrible life are less fraught, even felicitous. And it’s no wonder that this newsman-turned-novelist, known for his spare writing style and taut plotting, was daunted by the task of condensing the action-packed chronicle of his alter ego — a man who, like another Dexter character, Miller Packard (from the 2003 novel “Train”), sees himself “from a distance” and mistrusts introspection. “Sometimes, when he thought about it,” Dexter wrote of Packard, “it seemed like he’d been someplace else, watching himself, for most of his life.” The same could be said of Spooner. But in some 500 pages, Dexter brings Warren Spooner to ground and to life with uncharacteristic expansiveness and tenderness.

“Spooner” is a family epic that digs out the emotions packed in memory’s earliest bonds — guilt, resentment, loyalty and love. For Spooner, the guilt and resentment attach mostly to his mother, a querulous asthmatic who impressed upon him the unique agony of his birth (which his better-looking twin brother failed to survive), and who let him know that his existence was a continuing source of distress — crying out “God, how long can I stand it?” and weeping into a dish towel or a pillow over the various miseries of motherhood. His loyalty and love (at least until he becomes a husband and father) attach to a series of unappetizing dogs and to his stepfather. Spooner’s biological father died when his son was a baby, but the boy was spared a fatherless childhood by the arrival in Milledgeville of Calmer Ottosson, a disgraced young naval commander whose seafaring career was cut short by the botched burial-at-sea of an obese congressman. To the great fortune of what remained of the Spooner family — Spooner; his clever older sister, Margaret; and his mother, Lily — Calmer ended up teaching school in Milledgeville and speedily married Lily. Handy and dutiful, nurturing but reticent, Calmer instills in the boy a sturdy, quiet code of male behavior. At the age of 4, Spooner hungrily soaks up Calmer’s example. When he sees his sister take their future stepfather’s hand, he follows suit: “Without knowing he was doing it,” Dexter writes, “Spooner reached for a hand too, and got Calmer’s little finger instead, and they walked that way to the end of the block, and then Calmer stopped and gently pried him loose. ‘Men don’t hold hands,’ he said.” Oh, the pity of masculine detachment!

But when Spooner perversely plants himself in an anthill crawling with thousands of stinging insects, it’s Calmer who rescues him, brushes the ants off him and bathes him, soothing, “Easy does it . . . just take it easy,” and it’s Calmer who watches over the sickbed. Years later, Spooner remembers “the man sitting in the dark on the chest beside the bed, helpless, and the child lying in the dark beneath him, pretending to sleep, also helpless” — the two united in their manly vow of silence, and in their unspoken affection. When Spooner, in late adolescence, briefly becomes a baseball star, it’s Calmer who goes to his games, Calmer who tells him to keep his signing bonus from the Cincinnati Reds rather than turn it over to the family (because “you can never tell when you might need it”), and Calmer whose face Spooner sees when he awakes from surgery on his shattered, irretrievably wrecked pitching arm.

These stoical lessons help Spooner weather the adversities he meets once he’s on his own — like his first boss, in Florida, a “clean-cut, low-living sort of human outcast named Stroop” who sells baby pictures door to door, and tickles Spooner with a cattle prod before handing over his paycheck. (Spooner submits to the overture to get the money, then quits and becomes a journalist.) Among Spooner’s other adversaries are the stream of women who warm to, then instantly cool on him, “like they’d wandered into a pet store and almost bought a monkey,” and the men he meets with in Philadelphia to apologize for writing an article they disliked, who break his back and bash in his face. “Spooner had empathy to a fault, perhaps had learned it from Calmer.”

Empathy certainly betrayed him in Philadelphia. And yet, any reader who knows Dexter’s biography, so closely entangled with Spooner’s, knows that it’s this very attribute, and the horrendous 1981 attack it provoked, that moved Dexter to start writing novels. If it’s a fault, it’s one that has been redeemed in both blood and ink.